<meta name="google-site-verification" content="0S72xkYcSqqt100ZuIzn_Zif1zL8vIvcXUmc5Tjo10o" />

Key points to remember: Since ancient times, the waqf has financed schools, hospitals and infrastructure without riba, via inalienable property generating perpetual income. A legal and spiritual institution, it built a welfare state before its time, like the Ruma well, still functioning after 1400 years. A model of ethical and sustainable finance to be rediscovered for investments aligned with today's values.

Modern financial systems, often disconnected from human values, leave many citizens in search of ethical and sustainable models. Did you know that historic waqf, ancestral Muslim foundations, have built universities such as Al-Qarawiyyin (9th century) or hospitals such as Nour al-Din in Damascus, offering free and sustainable care, without resorting to riba? Explore how these concrete examples, combining progress and spirituality, have shaped supportive societies. Discover a legacy where every gift is transformed into sadaqa jariya, sowing trust and growth across the centuries, while preserving financial independence and the baraka of an inalienable asset.

Contents

Waqf, more than just a donation: an introduction to the pillar of Islamic civilization

Imagine a university or hospital that has been in operation for over a thousand years, providing services free of charge to entire generations, without ever having to resort to an interest-bearing loan. This is no utopia, but the legacy of the waqf (وقف), the inalienable philanthropic foundations that shaped the Islamic economy and society.

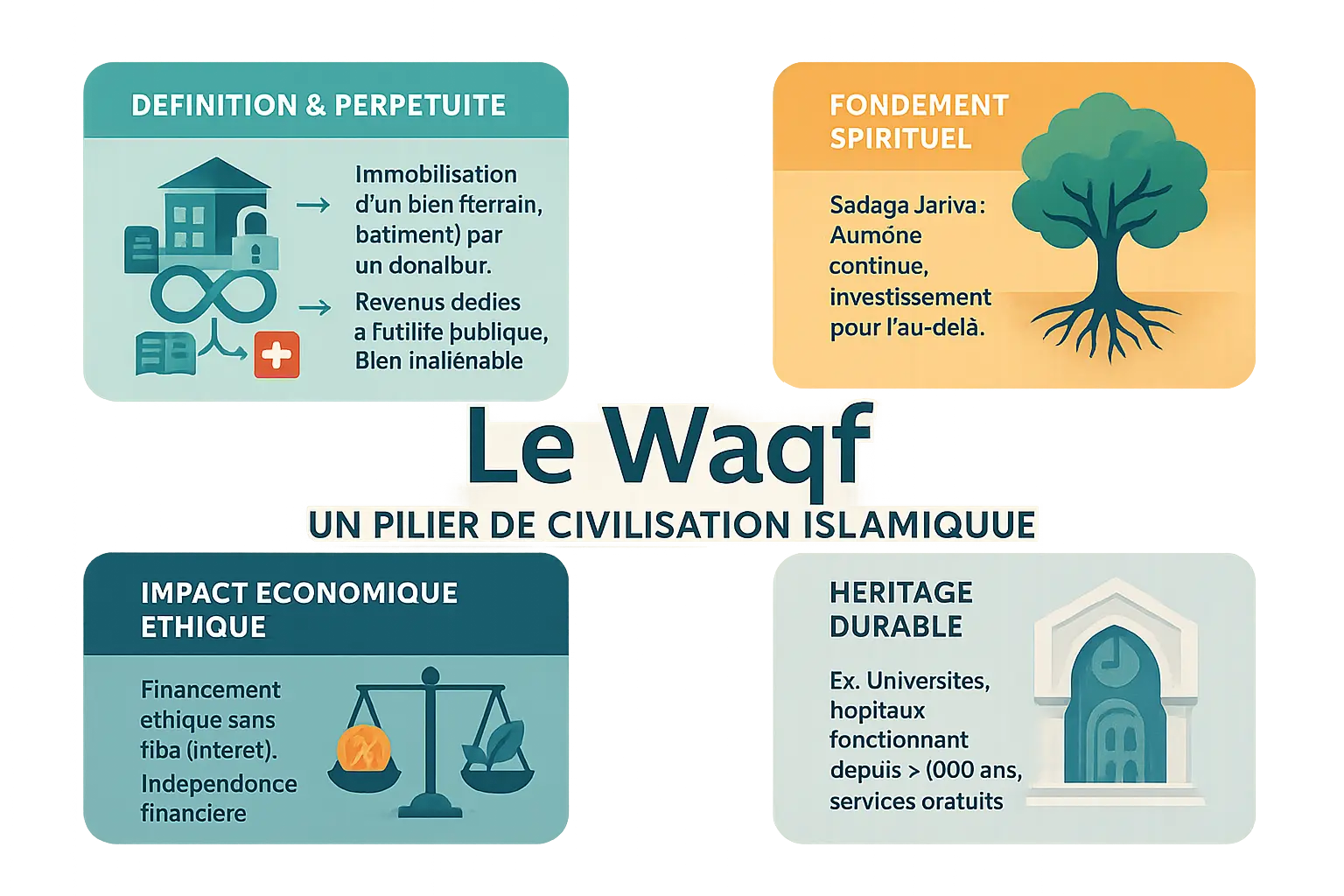

Il consiste à immobiliser un bien (terrain, bâtiment, argent) pour en consacrer les revenus à une cause d’utilité publique. Ce principe, ancré dans l’islam, transforme le capital en une ressource inépuisable au service de la communauté. Contrairement aux donations ponctuelles, le waqf est éternel : le bien reste intact, mais ses bénéfices irriguent éducation, santé, et solidarité.

On a spiritual level, waqf embodies sadaqa jariya (continuous almsgiving), a source of baraka (blessings) that endure after the donor's death. It is an investment in the hereafter, but also a practical response to earthly needs. By avoiding riba (interest), it proposes an ethical economic model, where justice and faith guide exchanges.

This article explores proven historical examples: universities funded by female donors like Fatima al-Fihri, Ottoman hospitals treating thousands of patients free of charge, or water systems built by waqf. Discover how these institutions have solved major social challenges, and why their model remains an inspiring alternative to capitalist exploitation.

The origins of waqf: early prophetic examples and their lasting impact

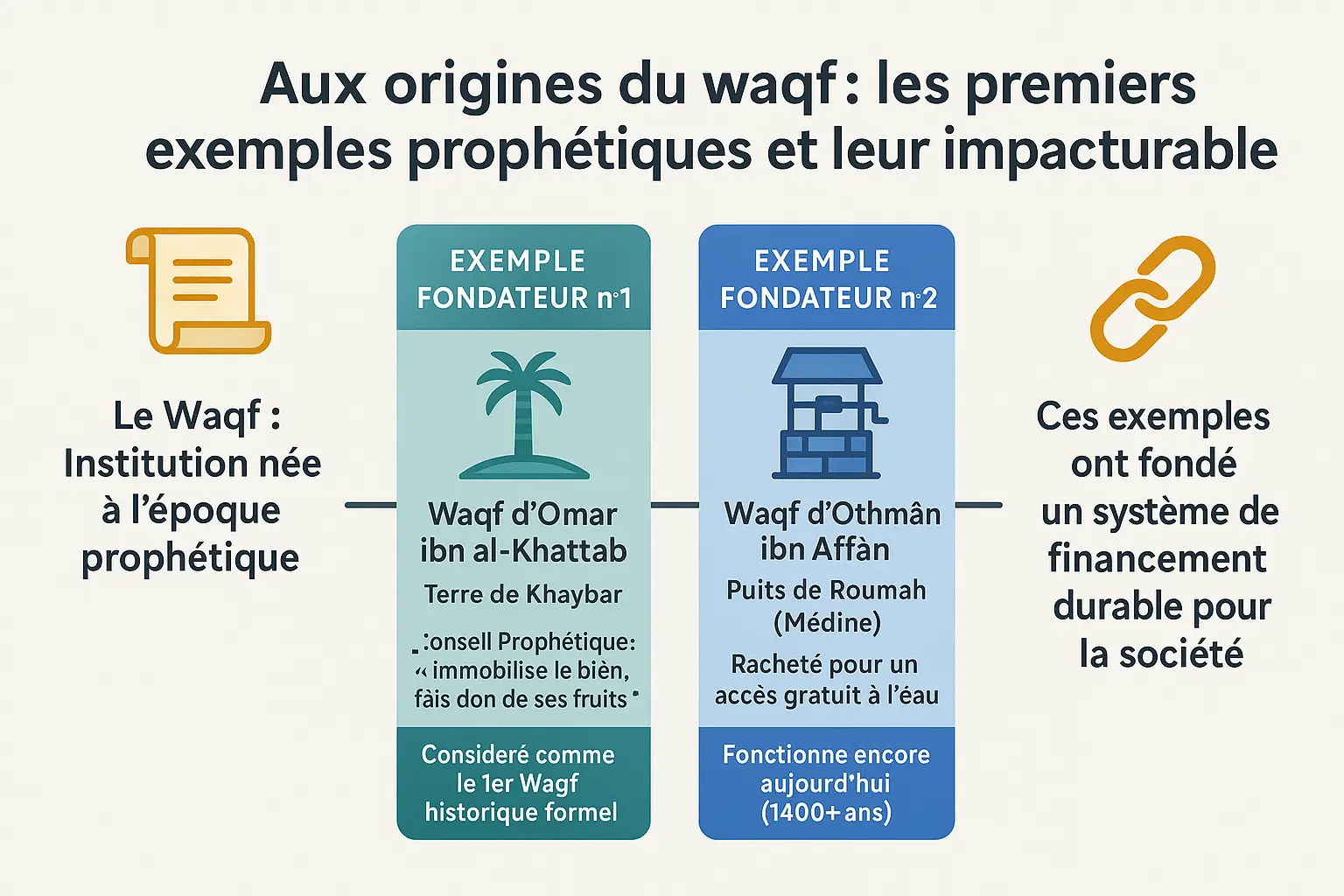

Waqf is a pillar of the Islamic economy: immobilizing property to devote its income to an eternal cause. This practice, born at the time of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, is based on a bold vision: transforming earthly wealth into heavenly benefit. Two prophetic accounts shed light on its genesis.

Omar ibn al-Khattab's visionary choice

After the conquest of Khaybar, Omar ibn al-Khattab (رضي الله عنه) was given exceptionally fertile land. Consulted by the Prophet, he received this historic reply: 'Immobilize the good and distribute its fruits' (Sahih Muslim). The land became the first formalized waqf, its harvests helping the needy, travelers and fighters on Allah's path.

Uthman ibn Affan's eternal well

In Medina, access to water was a challenge. The Rumah well, owned by a demanding merchant, was purchased by Uthman ibn Affan (رضي الله عنه) after the Prophet called out, "Who will offer a garden in Paradise in exchange for the well?" (Sahih Bukhari). Uthman made it a waqf after acquiring it completely. Today, the well still provides water after more than 1400 years.

The strength of a timeless model

These founding acts reveal the depth of waqf. Unlike one-off alms, this practice establishes a constant stream of benefits, a sadaqa jariya (continuous almsgiving) that succeeds where conventional economic systems fail. These stories laid the foundations for a system that would finance mosques, hospitals and universities for centuries to come.

When knowledge was a shared treasure: waqf in the service of education

At the height of the golden age of Islamic civilization, waqf gave generations access to free, independent and sustainable education. This mechanism of perpetual giving built an ecosystem where knowledge was not a commodity, but a collective heritage. World-renowned universities such as Al-Qarawiyyin and Al-Azhar have benefited from this vision.

Fatima al-Fihri, a visionary woman of the 9th century, founded Al-Qarawiyyin University in Fez in 859 thanks to a waqf funded by her personal inheritance. This pioneering project, recognized by UNESCO as the oldest continuously operating university, enabled scholars such as Ibn Khaldun and Ibn Rushd to flourish. Even today, its archives house precious manuscripts, a reminder that philanthropy can transform dreams into eternal legacies.

The waqf made it possible to build an ecosystem where knowledge was not a commodity, but an inheritance accessible to all, regardless of wealth or origin.

In Egypt, Al-Azhar University, founded in the 10th century, exemplified a similar ambition. Supported by an extensive network of waqf, it provided salaries for lecturers, scholarships for needy students, accommodation and even daily meals. This innovative structure enabled thousands of scholars to devote themselves fully to their studies, without material constraints.

- Funding of teachers' salaries to guarantee academic excellence.

- Awarding scholarships to deserving and destitute students.

- Provision of free accommodation and meals to enable full concentration on studies.

- Purchase of books and equipment for university libraries.

Derrière ces réalisations, le waqf incarnait une sadaqa jariya (aumône continue) aux retombées spirituelles et sociales profondes. En libérant l’éducation du riba, il a favorisé un modèle éthique, où la connaissance devenait un bien commun. Cette leçon du passé inspire encore aujourd’hui ceux qui cherchent à réconcilier croissance économique et valeurs humaines. N’est-ce pas là une manière de cultiver la baraka (bénédictions) dans le monde moderne ?

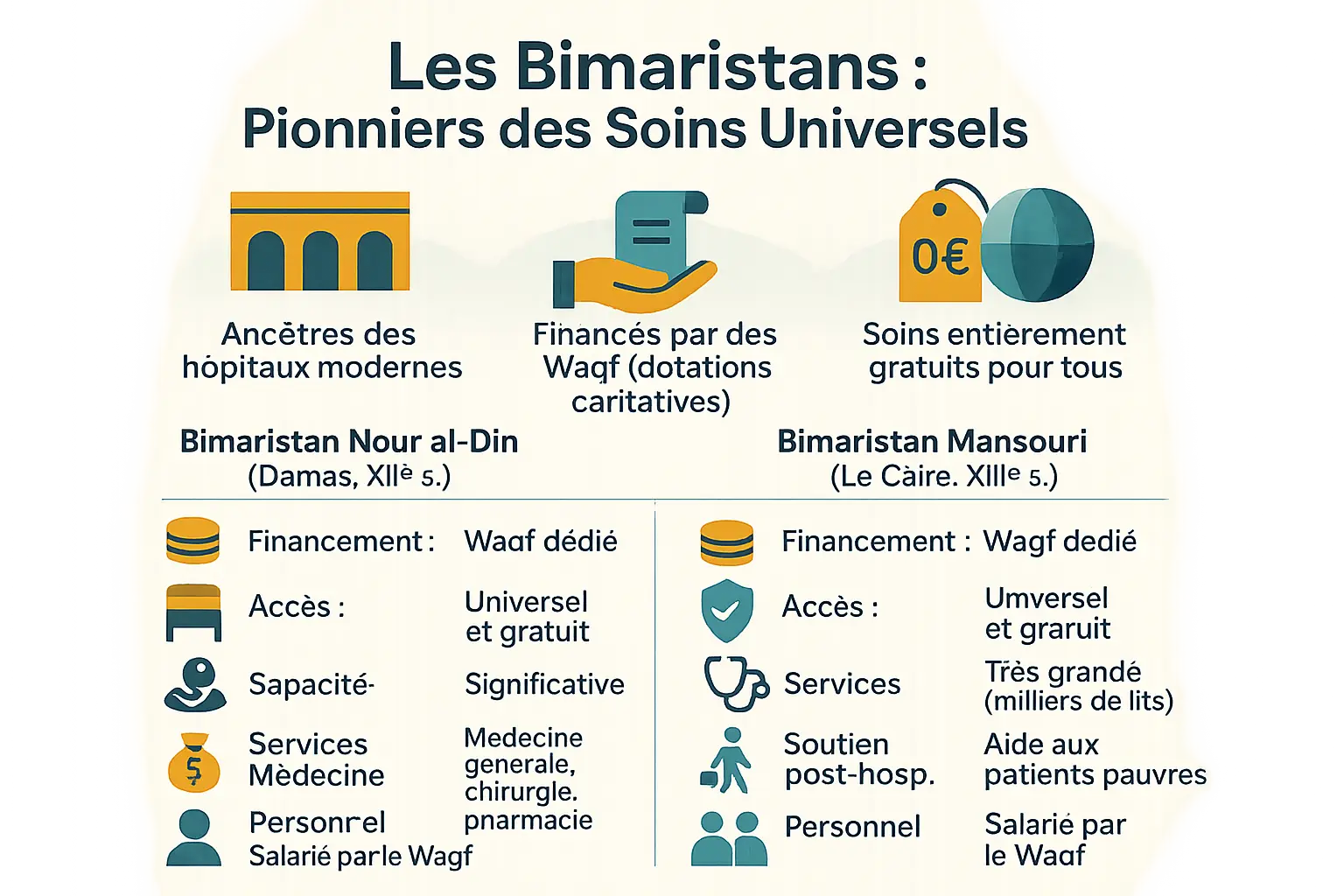

Bimaristans: how waqf invented public hospitals and free healthcare

Bimaristans, the forerunners of modern hospitals, embodied the waqf's community and spiritual commitment. Financed by perpetual donations, they offered universal care without social distinction, prefiguring our current health protection systems.

nour al-din's bimaristan: a model of human innovation

Founded in Damascus in 1156 by Nur al-Din Zangi, this bimaristan revolutionized medieval medicine. Financed by a real estate waqf, it was open free of charge to all social categories, Muslim and non-Muslim alike. Innovations included systematic medical records, an integrated pharmacy and post-hospital financial support for the poor.

Bimaristan Mansouri: pioneering psychiatric care

Built in Cairo in 1284 under Qalawun, this hospital giant housed up to 8,000 patients. Its waqf covered innovative psychiatric care: music therapy, natural light. Patients were given food rations on discharge to prevent post-hospitalization hardship.

| Features | Bimaristan Nur al-Din (Damascus, 12th c.) | Bimaristan Mansouri (Cairo, 13th c.) |

|---|---|---|

| Financing | Waqf real estate | Waqf real estate |

| Access to care | Universal and completely free | Universal and completely free |

| Capacity | Significant for its time | Very large (4,000 to 8,000 beds) |

| Our services | General medicine, surgery, pharmacy | General medicine, specialties, psychiatric care |

| Post-hospitalization support | Convalescence allowance | Discharge support for poor patients |

| Staff | Doctors, nurses and pharmacists employed by waqf | Full medical and administrative staff financed by waqf |

A sustainable economic and spiritual model

Revenues from waqf properties (land, stores, caravanserais) ensured long-term financing. In keeping with the principle of sadaqa jariya, these donations generated a continuous baraka for society. This independence from riba made it possible to maintain an ethical healthcare system, foreshadowing our social protection systems.

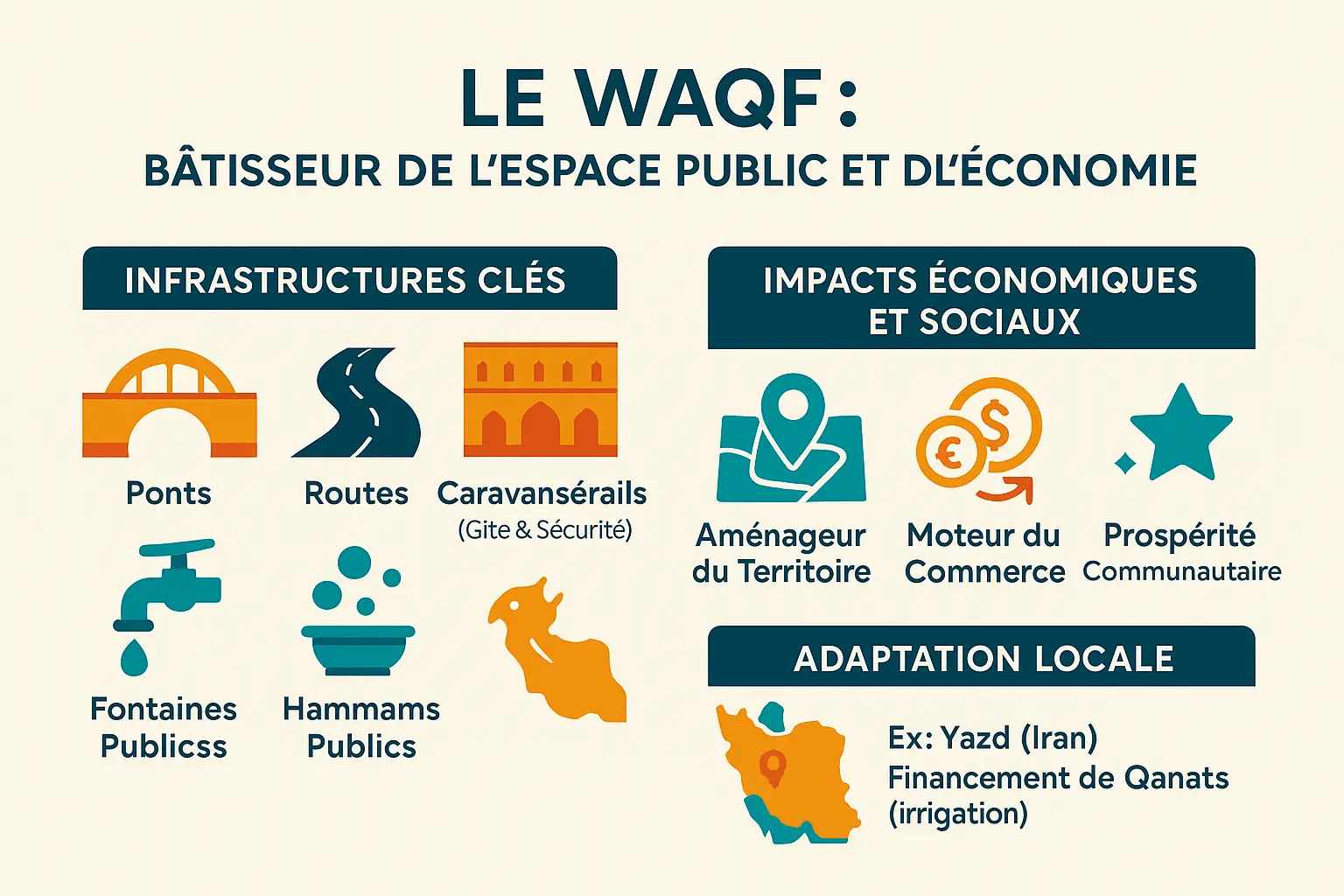

Bridges, roads and fountains: when the waqf built public space

À l’apogée de l’Empire ottoman, chaque route parcourue, chaque goutte d’eau puisée dans une fontaine publique racontait l’histoire d’un don générationnel. Ces infrastructures formaient le socle caché de la prospérité islamique, reliant villes et déserts par une logique d’éternité. Les routes de pèlerinage et commerciales devenaient des réseaux de bénédiction.

The waqf as land developer

Under the Ottomans, half of Egypt's agricultural land was managed as waqf. This system extended its logic to public development: solid bridges crossed rivers, paved roads linked oases, facilitating risk-free trade. In Aleppo, these axes structured the spice and cotton trade.

Caravanserais, pillars of trade

These fortified inns exemplified the riba-free economy. In Turkey, 1,2000 caravanserais linked Istanbul to Baghdad. The caravanserai of Sultanhanı (13th century) offered accommodation and security to silk merchants. Each stop stimulated trade along 6,000 km of road, financing mosques and hospitals. Caravans also transported manuscripts and knowledge.

Innovation adapted to climate challenges

In the deserts of Iran, Yazd's qanats, maintained by pious foundations, carried water for miles. This historic city prospered thanks to these networks, irrigating apricot orchards and gardens. The public fountains (sabil) of Damascus and Cairo, fed by marble systems (salsabil), were a daily reminder of this collective blessing. In Jerusalem, sabil-kuttabs combined water distribution and Koranic education.

These rusting bridges and dried-up fountains bear witness to an economic model in which baraka took precedence over profit. Eternal infrastructures, inviting us to rethink modern investment as a legacy to the community, where ethics guide stone and commerce.

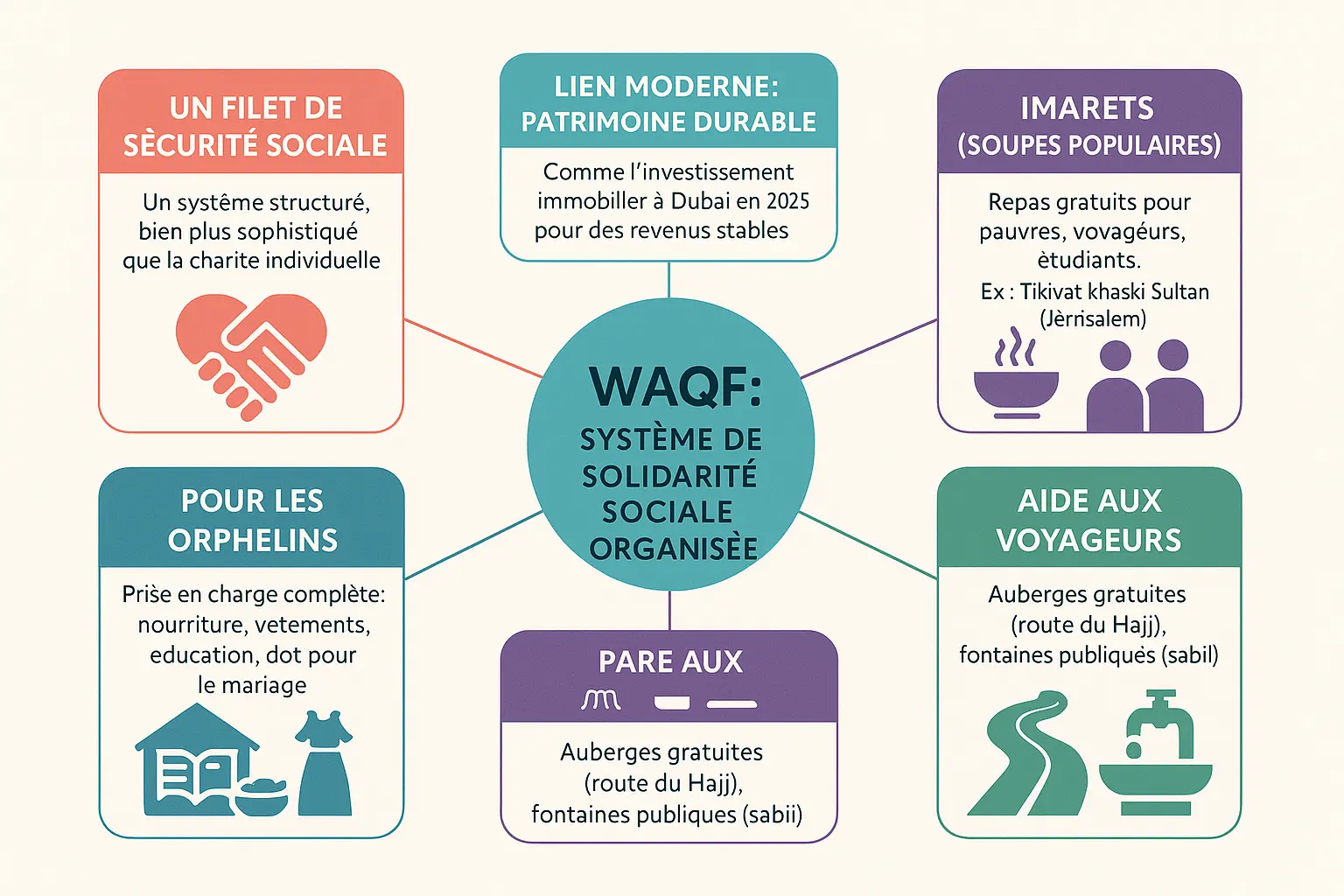

Beyond almsgiving: the waqf as an organized system of social solidarity

A social safety net

The waqf was not a one-off alms, but a solid legal system that immobilized assets (land, buildings) to generate sustainable income. Independent of riba, it met social needs without altering capital, similar to the principle of sadaqa jariya (continuous almsgiving).

Concrete examples of solidarity

Waqf for orphans: In Mamluke Egypt, foundations provided for their education, health and dowry. Cairo schools in the XIIIᵉ century offered food, lodging and allowances to disadvantaged pupils.

Imarets, Ottoman soup kitchens: these charitable kitchens, like the Tikiyat Khaski Sultan in Jerusalem (1552), distributed free meals. In Istanbul, they fed up to 30,000 people daily.

Help for travelers and access to water: waqf-funded sabil (fountains) and Hajj inns supported pilgrims. The Zubayda Way (IXᵉ century) provided cisterns and shelters, illustrating the baraka linked to generosity towards travelers.

An inspiring heritage for modern investment

The waqf model, based on asset permanence, resonates with halal real estate. Just as these foundations managed farmland and businesses to finance hospitals or schools, investing in stable markets such as Dubai real estate in 2025 embodies a modern strategy rooted in social justice and sustainability. This link between tradition and ethics illustrates how waqf, an age-old tool of solidarity, can guide ethical economic solutions for the XXIᵉ century.

Guaranteeing eternity: the rigorous management and durability of waqf

How have waqfs survived the centuries to serve the public good? Thanks to two pillars: an unshakeable legal structure and a supervised management system. These foundations transform a donation into a sustainable economic mechanism, inspiring modern Islamic investment.

The secret of longevity: durability and inalienability

The waqf is based on a key principle: the removal of an asset from the commercial cycle. Once consecrated, the good becomes "divine property", inalienable. It cannot be sold, given away or inherited. This guarantee ensures eternal income for society. A permanent philanthropic giftA permanent philanthropic gift, capable of financing schools or hospitals without being dependent on the ups and downs of the economy.

The mutawalli: guardian of sacred property

Appointed by the founder, the mutawalli rigorously manages the estate. He maintains assets, collects rents (land, stores) and redistributes income in accordance with the donor's wishes. In the Ottoman Empire, this role financed mosques and inns via stores and mills.

A key figure in the Islamic economy, he carries a moral responsibility: to preserve the "baraka" of goods, that blessing passed on to future generations. His management transforms an individual gift into a collective legacy.

Controls to preserve integrity

The sustainability of waqf relies on institutional safeguards. The cadi (Islamic judge) supervised funds as early as the VIIIᵉ century via dīwān in Egypt. These structures ensured that every dirham served the public interest.

Historically, the Ottoman Empire dedicated 50-66% of its land to awqaf, financing schools and roads. Today, Oman and Morocco perpetuate their management through specialized ministries.

By guaranteeing the inalienability of assets and external control, the waqf embodies a timeless alternative to ephemeral capitalism. It proves that ethical investment, rooted in spirituality, can build a sustainable future for all generations.

A welfare state before its time: the economic and social impact of waqf

Imagine a society where education, health care, drinking water and social assistance were accessible to all, without depending on the whims of political power or economic fluctuations.

This collective dream has been a reality in the history of Islam thanks to the waqf system, a perpetual donation that functioned as a veritable welfare state long before the concept was invented in the West.

From the 9th century onwards, waqf formed a dense network of independent institutions, managed by mutawallis, who ensured the continuity of public services.

This sophisticated system made it possible to finance essential needs without resorting to riba, guaranteeing economic stability and financial sovereignty.

The waqf have created:

- A powerful, autonomous non-profit sector

- Sustainable funding for public services

- Stimulation of the local economy through infrastructure construction and maintenance

- Reducing inequalities and social cohesion

In Mamluk Egypt, almost half of all farmland was awqaf, generating stable income for the collective well-being.

In the Ottoman Empire, between half and two-thirds of land was waqf, supporting education, health and infrastructure.

This economically viable and socially just model has enabled Muslim communities to prosper for centuries, aligning ethics and sustainable development.

In Jerusalem, the 16th-century Haseki Sultan complex financed social services in 26 villages, while in 15th-century Egypt, waqfs fed 800,000 people daily through imarets.

This system embodied sadaqah jariyah (continuous almsgiving), transforming assets into perpetual benefits for society, not to mention the baraka inseparable from responsible asset management.

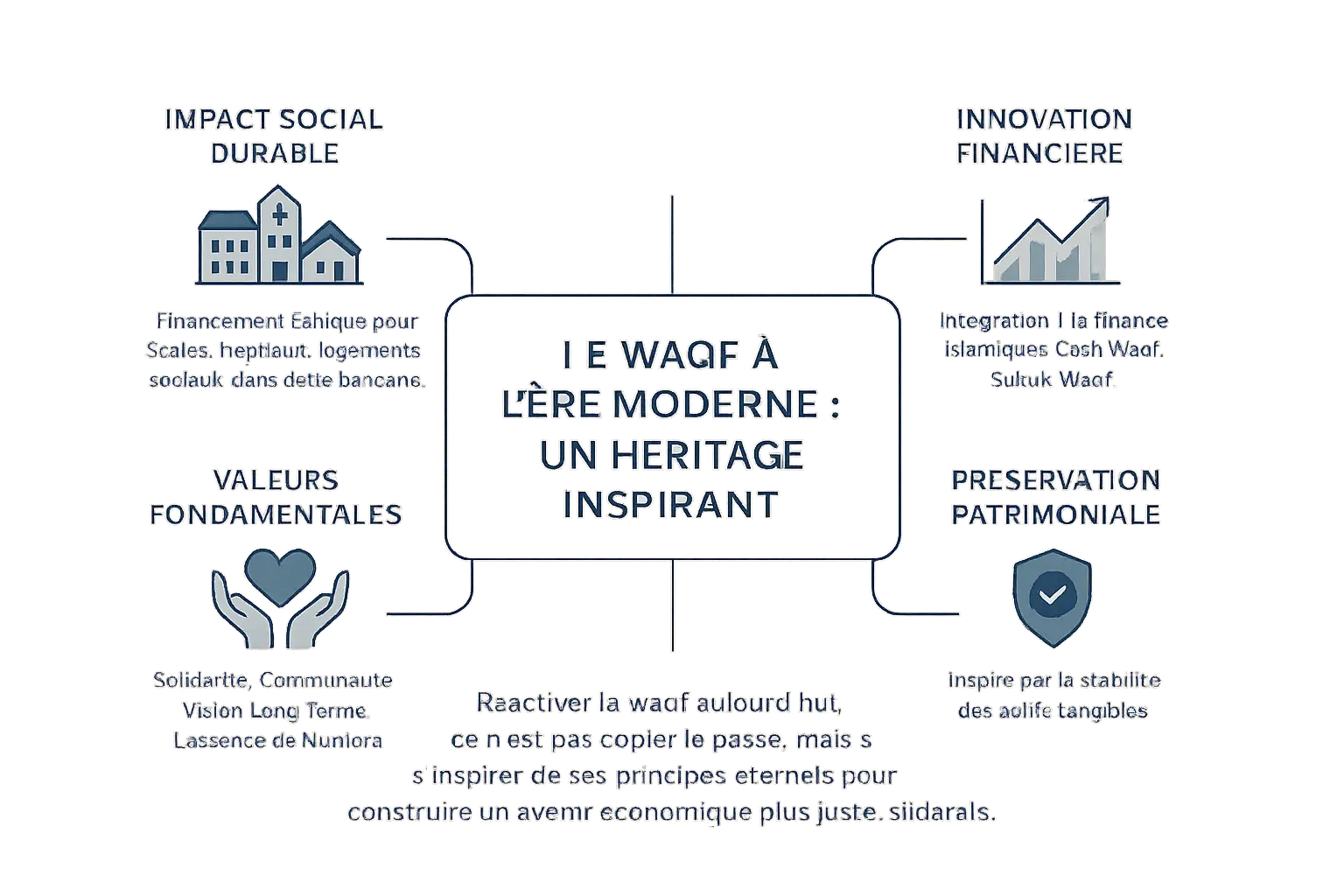

Waqf in the modern age: an inspiring legacy for ethical finance

Are you wondering whether waqf, those philanthropic foundations rooted in Islamic history, no longer have a place in today's world? History says no. Historical models, such as Al-Qarawiyyin or Al-Azhar universities, show that waqf has always been a lever for long-term projects: schools, hospitals or social housing. Today, this logic is being reinvented to meet modern challenges.

Contemporary Islamic finance is rediscovering the potential of waqf. Cash waqf", like sukuk-waqf in Indonesia, transforms monetary donations into productive assets. These Sharia-compliant instruments invest in social projects while preserving the initial capital. Initiatives such as the Achmad Wardi eye hospital in Serang illustrate how an ancestral model can finance modern medical infrastructures.

The spiritual essence of waqf remains unchanged: it embodies a sadaqa jariya, a continuous almsgiving that goes beyond the quest for profit. For Namlora, this heritage resonates deeply. Just as waqf aims to preserve and grow value through the ages, investing in tangible assets recognized for their stability, such as halal gold online, is part of a logic of heritage protection and transmission.

Reactivating the waqf today means not copying the past, but drawing inspiration from its eternal principles to build a fairer, more united and sustainable economic future.

Modern waqfs, managed by competent mutawalli, offer an alternative to individualistic capitalism. By incorporating mechanisms such as cash waqf linked sukuk (CWLS), they stimulate the economy without resorting to riba. In Indonesia, CWLS programs have financed educational scholarships, medical equipment and support for micro-enterprises, proving that this model is still relevant today.

By bringing this principle back to life, Namlora embodies this vision: uniting spirituality, transparency and innovation for economic development aligned with Islamic values. The waqf, a living heritage, remains a concrete response to the call of baraka and social justice.

The historic waqf, a compass for a fairer, more sustainable future

Il incarne une vision économique et spirituelle intemporelle. En immobilisant des biens pour le bien commun, cette pratique a permis aux sociétés musulmanes de financer éducation, santé et solidarité en rejetant le riba. Un héritage inspirant une finance responsable.

Each waqf reveals a legacy of generosity. Al-Qarawiyyin University, founded by Fatima al-Fihri, or the hospitals in Damascus and Cairo, prove its effectiveness. These examples show how vital infrastructures were supported by this model, creating an autonomous economic fabric.

The waqf goes beyond the financial. It embodies social justice, where every act serves the community. The mutawalli, a dedicated manager, guarantees its continuity by transforming donations into collective benefits. In a world in crisis, this model remains a benchmark.

Why revive this tradition? Its lessons:

- Perenniality: A waqf property serves its cause forever, avoiding speculation.

- Social impact: Success is measured in lives transformed, not sales.

- Independence: By rejecting riba, waqf prefigured an ethical economy.

Il n’est pas un vestige, mais une solution vivante. En s’inspirant des mosquées-écoles du Xe siècle ou des hôpitaux du XIIe, l’écosystème Namlora redonne vie à ce principe. Il s’agit de placer justice et spiritualité au cœur des échanges, pour un avenir où la finance sert l’humain. L’histoire le prouve : un don permanent peut planter la graine d’un monde plus juste.

The waqf, a living legacy of Islamic finance, embodies a timeless vision of social justice and ethical economics. By reactivating its principles - sustainability, social impact and financial independence - we can reinventing finance for peoplecombining tradition and innovation to build a resilient, mutually supportive future.

FAQ

What is the history of waqf in Islam?

Waqf dates back to prophetic times, with seminal acts such as the acquisition of the Roumah well by Othman ibn Affan, offered free of charge to Muslims. From the 8th century onwards, the practice was structured to finance mosques, schools and hospitals. Early examples, such as the land at Khaybar awarded by Omar ibn al-Khattab on the advice of the Prophet ﷺ, laid the foundations for a lasting system. Waqf networks then flourished under the Umayyads, Abbasids and Ottomans, covering education, health, infrastructure and social solidarity. Today, this model inspires modern Islamic finance for ethical and sustainable projects.

What is the history of Islam?

L’islam naît au VIIe siècle avec la révélation du Coran à Mohamed ﷺ. En quelques décennies, le message s’étend de l’Arabie à des territoires vaste, de l’Espagne à l’Inde. L’histoire de l’islam se nourrit de son unité fondamentale – la foi en un Dieu unique – et de ses piliers, dont le waqf, qui a structuré les sociétés musulmanes. Ces institutions caritatives, nées sous les premiers califes, ont permis de bâtir des universités comme Al-Qarawiyyin (IXe siècle) ou des hôpitaux pionniers comme le Bimaristan de Damas. L’islam a ainsi allié foi et pragmatisme, créant un héritage culturel et social encore vivace aujourd’hui.

What is the meaning of the word "waqf"?

The term "waqf" (وقف) refers to the immobilization of an asset (land, building, money) to devote its income to a lasting cause. It's not a simple gift, but a perpetual act: the good becomes inalienable, like a generous tree whose fruits nourish society. Spiritually, it is a sadaqa jariya, a continuous almsgiving that rewards the donor even after death. Economically, it is a lever for independence from riba, a tool for building an ethical and resilient legacy, like the Ottoman bridges or public fountains of yesteryear.

What is the Jerusalem Waqf?

The Jerusalem Waqf, overseen by the Islamic Waqf (a religious authority), protects the city's holy sites, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Historically, the Waqf has helped preserve Jerusalem's spiritual and cultural heritage in the face of geopolitical pressures. Initiatives such as the Takiyyat Khaski Sultan, a free hostel for travelers founded in the 16th century, illustrate the social dimension of this system. Today, despite the challenges, this waqf embodies ethical resistance, guaranteeing access to sacred sites while supporting educational and humanitarian projects in the Old City.

How does a waqf work?

A waqf is created by an irrevocable deed of gift of an asset (e.g. a plot of land, a store), the income from which (rents, harvests) is used for a specific cause - education, health, water. The property is inalienable, managed by a mutawalli (manager), under the supervision of a judge (qadi) to comply with Islamic law. For example, waqf agricultural land generates rents to maintain a school, such as Al-Azhar in Cairo. This mechanism, combining stability of capital and fluidity of profits, has financed public infrastructure for centuries, from Damascus to Istanbul, while avoiding indebtedness.

Who was Allah before Islam?

In pre-Islamic Arabia, "Allah" was already venerated as the supreme God, creator and ultimate judge, even if polytheistic practices prevailed. Islam reaffirmeddivine oneness (tawhid), rejecting associates (shirk) and redefining Allah's role as sole Lord. This linguistic continuity, yet doctrinal rupture, sheds light on the spiritual depth of waqf: property consecrated to Allah transcends the ephemeral, becoming an eternal legacy for the community, as an investment in the hereafter.