<meta name="google-site-verification" content="0S72xkYcSqqt100ZuIzn_Zif1zL8vIvcXUmc5Tjo10o" />

Riba is much more than a religious prohibition; it is a financial anomaly that disrupts the economy, amplifying inflation and inequality. By favoring rents, it concentrates wealth to the detriment of modest households. A solution exists: purification (Tasqiyah) via the AAOIFI's 5% threshold can purify income indirectly exposed to Riba, helping Samira to align her financial choices with her values.

Le système financier moderne vous semble-t-il injuste, creusant les inégalités et piégeant les plus vulnérables dans un cycle de dettes ? La critique systémique de riba révèle comment l’intérêt, au cœur de notre économie, agit comme une tumeur qui pompe la richesse créée par le travail pour la concentrer entre quelques mains, tout en amplifiant crises et précarité. Découvrez dans cet article une analyse choc sur cette anomalie financière, ses mécanismes pervers de transfert de risques et ses liens avec la montée de la plutocratie, à travers le prisme de la finance islamique qui tente de réinventer un modèle éthique.

Contents

Riba: more than a ban, an anomaly at the heart of modern finance

In a world where finance seems increasingly disconnected from reality, many people, like you, are looking to give meaning back to their money. But how can we do this when the system itself seems skewed?

Riba (interest or usury) is one of the two fundamental prohibitions of Islamic finance, along with gharar (excessive uncertainty). Contrary to popular belief, this prohibition is not just an abstract religious rule, but the basis of a profound critique of the current financial system. Academic debates on the Riba-Interest equation show that this notion goes beyond religious boundaries to question the very logic of our economy.

Riba is defined as any surplus obtained without any real consideration in a loan or exchange. It is a guaranteed gain on time or the loan of money, unrelated to the productive economy. The Qur'an (2:275-276) explicitly forbids it while authorizing trade, underlining a crucial distinction: money must circulate fairly, not accumulate on its own.

This subject touches you deeply in your search for meaning, whether to understand the values of your grandparents or to invest according to your own principles. This article analyzes Riba as a financial anomaly with dramatic social and regulatory consequences, with concrete examples and practical solutions. Let's rediscover the logic of fairness in our relationship with money and gharar.

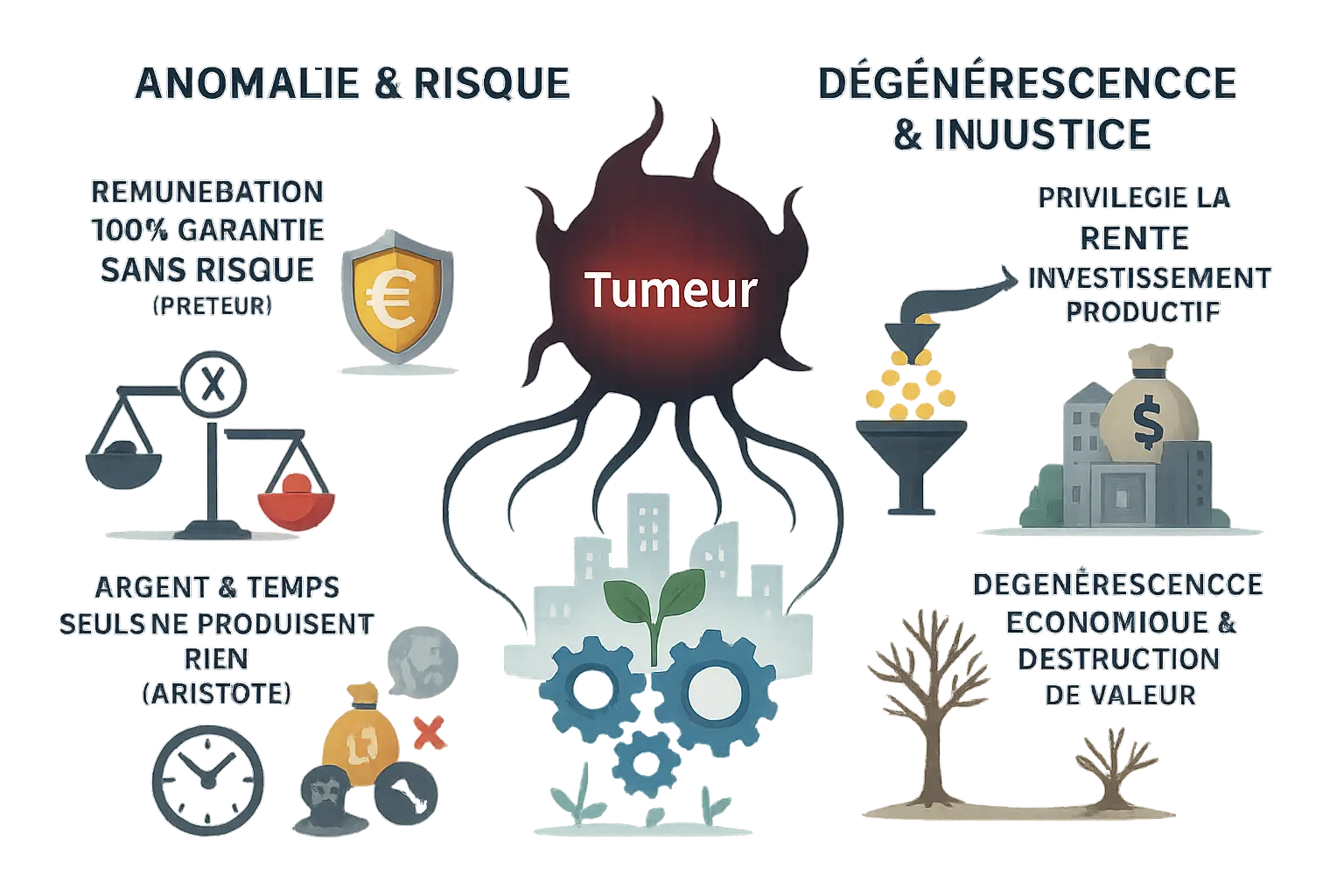

Interest: an unnatural anomaly and a source of economic injustice

Guaranteed remuneration and risk transfer

Riba is distinguished from other financial returns by its abnormal nature: it is a 100% guaranteed return with no risk taken by the lender. Aristotle, in Politics, already denounced this practice as "the most contrary to nature", criticizing the concept of money generating money(tókos in Greek, literally "offspring").

Instead of sharing risks between the parties, the system unilaterally transfers losses to the borrower. Even if the project financed fails, the lender recovers its capital plus interest, creating structural imbalances. This dynamic amplifies systemic risk, as losses spread exponentially during financial crises.

Money and time, by themselves, produce nothing. Capital is an accumulation of labor, and interest drains this value without contributing to it.

Economic degeneration: rent and value destruction

By favoring projects secured by tangible assets rather than by their productive potential, the interest system feeds rents to the detriment of innovation. An innovative company without solid collateral struggles to obtain financing, whereas a classic structure with real-estate assets easily obtains credit, even with low profitability.

This dynamic acts like a financial tumor, sucking resources out of the real economy. According to a scientific study, this phenomenon is criticized for its role in withdrawing the mobilization of productive resources, creating a vicious circle of wealth concentration.

By systematically protecting themselves against default, banks divert capital into low-risk, low-value-creating investments. This logic potentially destroys 25% to 40% of the wealth that a system based on risk-sharing could generate, according to the analyses of Islamic economists.

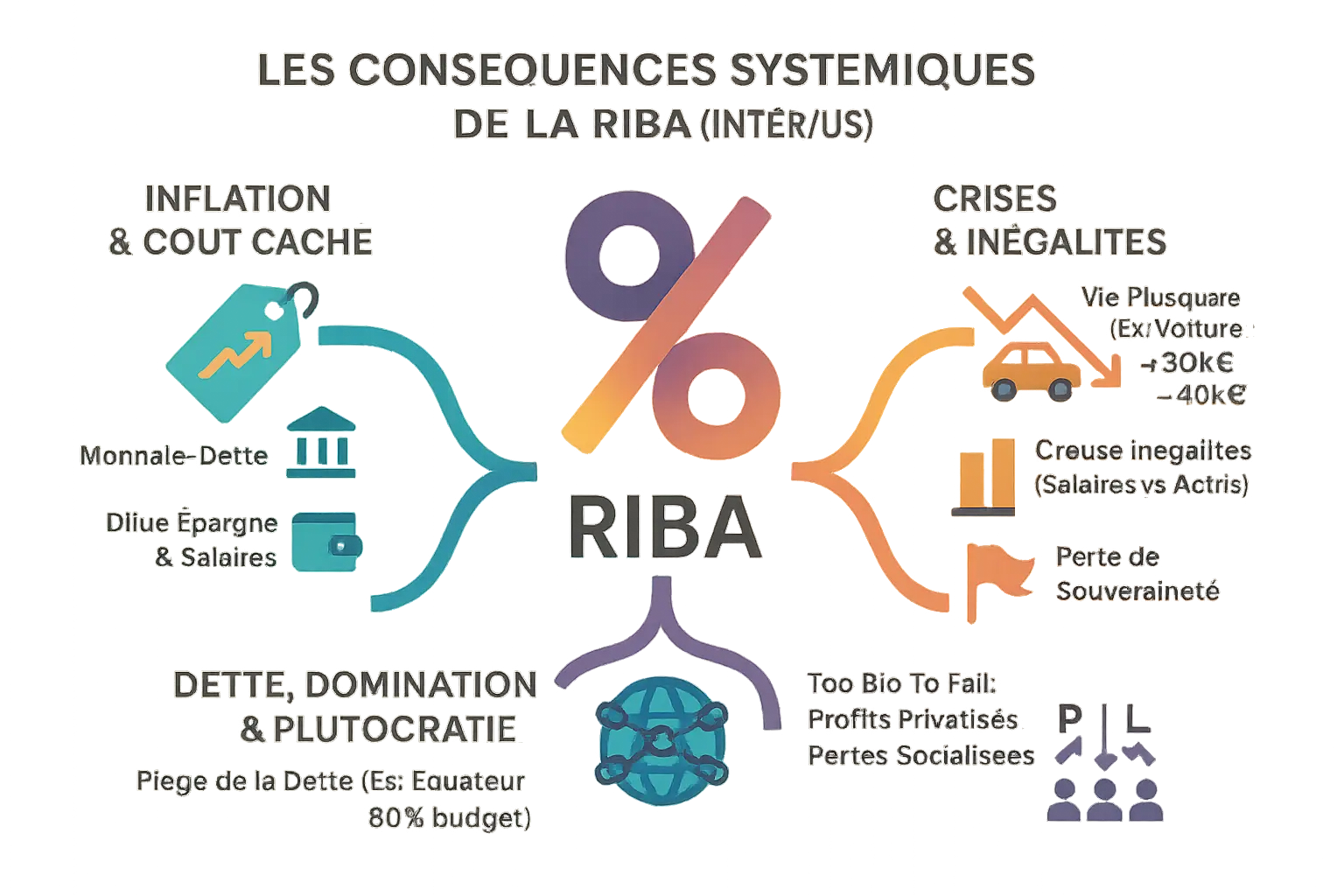

Systemic consequences: inflation, debt and plutocracy

Riba, a driver of inflation and a hidden tax

The debt-money system is based on the creation of money through credit, made attractive by interest payments. Banks are thus encouraged to multiply their lending, fuelling a monetary expansion that devalues the value of money. Inflation acts as a silent tax, taking wealth from the whole economy for the benefit of the financial sector.

Amplifying crises and social inequalities

Riba works like an economic doping: it exacerbates growth in good times, but amplifies recessions. The 2008 crisis in the United States led to 1 million property evictions, illustrating the damage caused by a system based on disguised interest. For an underprivileged person, a €30,000 property can cost up to €40,000 on credit, widening the gap.

- Widening inequalities: Inflation devalues wages more than assets, held mainly by the wealthiest.

- Increased cost of living: credit purchases (housing, cars) become prohibitive for low-income households.

- Creates instability: economic cycles become more violent, with more booms and busts.

To understand this effect, the cost of acquiring a property varies according to financing mechanisms, with concrete social impacts.

Debt as a political trap and the rise of plutocracy

Riba debt becomes a tool of domination. The history of Morocco in the 20th century demonstrates this: forced indebtedness to France led to the protectorate in 1912. International loans often benefit companies in the lending countries, leaving states over-indebted. In 2005, Ecuador devoted 80% of its budget to debt servicing, sacrificing education and health.

"In the event of bankruptcy (too big to fail), the system operates a privatization of profits to shareholders and a socialization of losses paid by taxpayers."

In developed countries, this model feeds the plutocracy. The banking lobby dominates decision-making in Washington and Brussels, benefiting from public subsidies and bailouts during crises, while profits remain private.

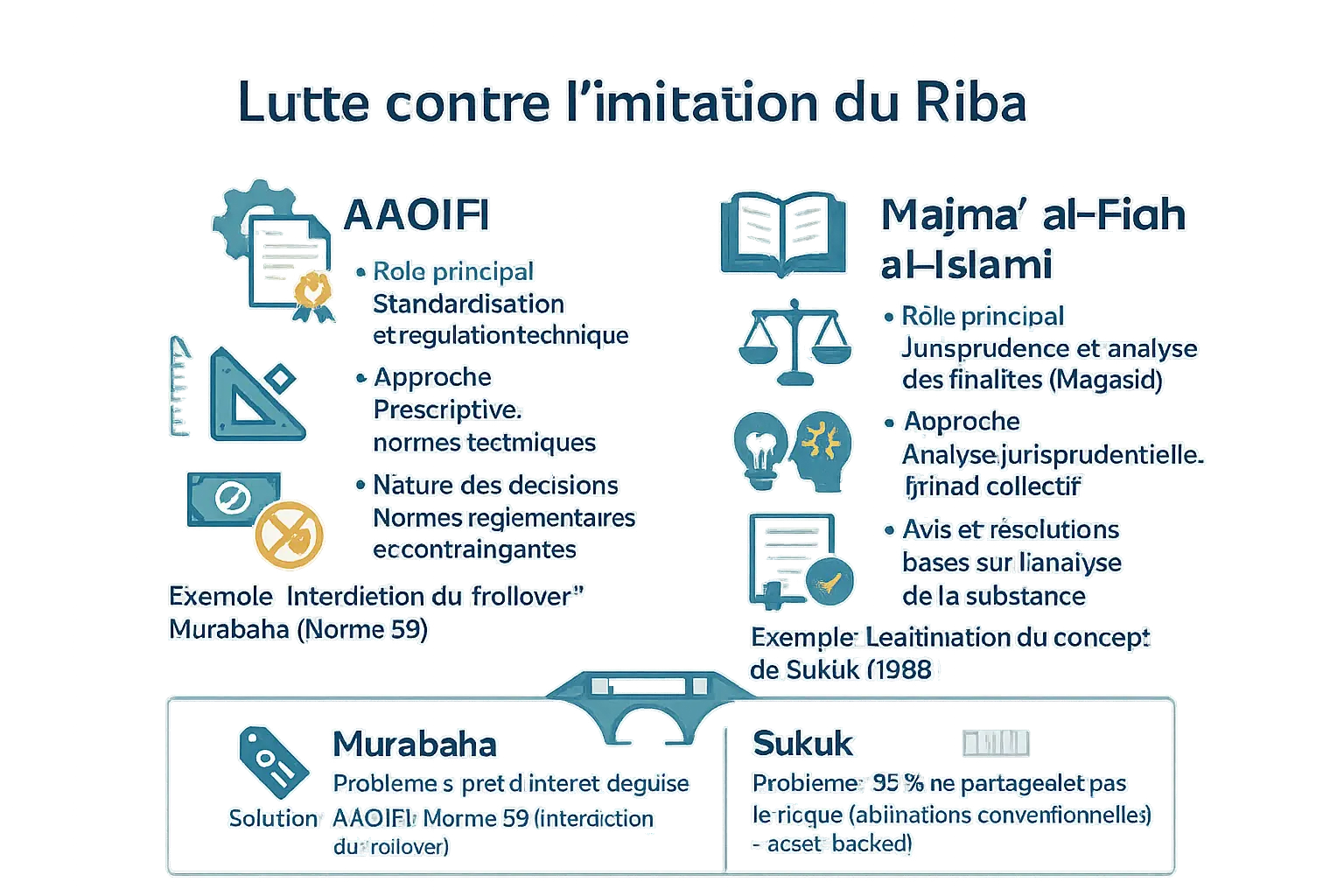

| Criteria | AAOIFI | Majmaʿ al-Fiqh al-Islami |

|---|---|---|

| Main role | Standardization and technical regulation | Jurisprudence and purpose analysis (Maqasid) |

| Approach | Prescriptive, issuing technical standards | Jurisprudential analysis, Collective Ijtihad |

| Nature of decisions | Binding regulatory standards | Opinions and resolutions based on substance analysis |

| Example of intervention | Prohibition of "rollover" in the Murabaha (Norm 59) | Legitimization of the Sukuk concept (1988) |

The role of the guardians of ethics: AAOIFI and Majmaʿ al-Fiqh al-Islami

Islamic finance rests on two institutional pillars: AAOIFI and Majmaʿ al-Fiqh al-Islami. AAOIFI, founded in 1991 in Bahrain, issues standards adopted by jurisdictions such as Kuwait and Sudan. Its standards lay down strict rules for each type of product.

The Majmaʿ, established in 1981 in Mecca, embodies the spiritual approach. This college of ulama analyzes transactions according to Maqasid (Shari'a purposes) rather than their mere legal form. Its pioneering resolution on Sukuk in 1988 validated an innovative financial tool in line with Islamic principles.

Their collaboration is aimed at combating hiyal, the ruses that transform conventional loans into seemingly Islamic products. For example, a Murabaha calculated on the basis of an IBOR rate + margin becomes disguised Riba, despite its different legal form. Without this vigilance, financial institutions could reproduce the abuses of the traditional banking system under an Islamic veneer.

Risky contracts: the case of Sukuk and Murabaha

Murabaha illustrates the challenges of Islamic finance. This cost-plus sales mechanism is valid in theory, but AAOIFI had to intervene via its Standard 59 to prohibit "rollover", the practice of renewing contracts that ended up resembling a disguised interest-bearing loan. Imagine a revolving loan: without this ban, banks would have been able to create endless cycles of variable-rate debt.

Sukuk, which are supposed to represent tangible assets, are problematic, with 85% of current issues not actually sharing risk. AAOIFI is preparing a new standard (62) requiring real transfer of ownership to avoid abuses. To find out more about these drifts, click here.

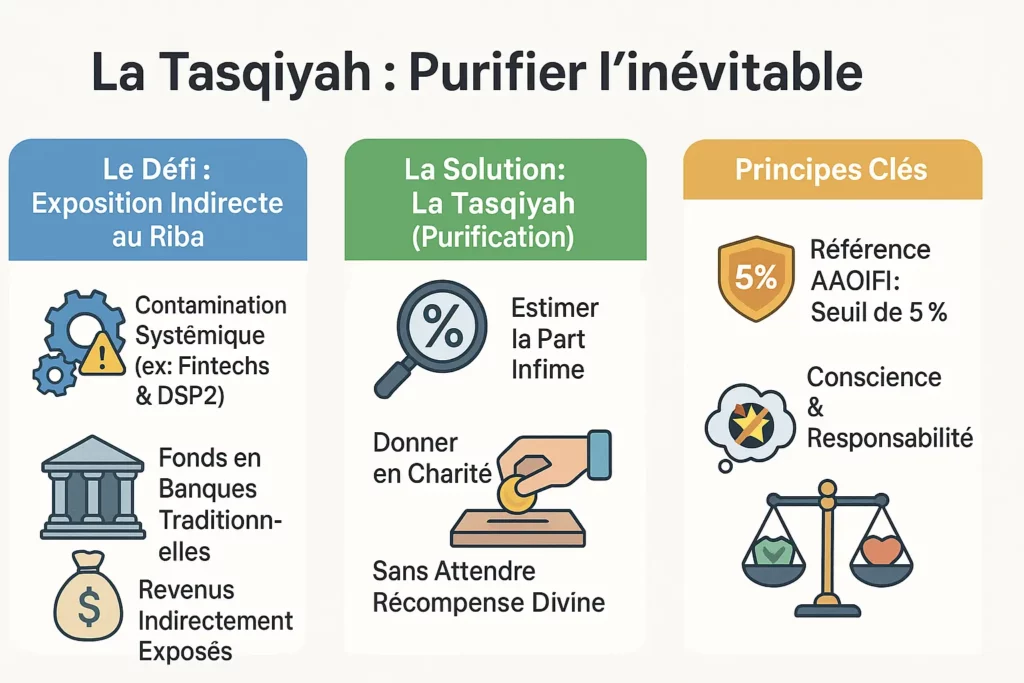

Even Muslim fintechs have to deal with the global financial system. To manage indirect exposure to Riba, Islamic finance advocates purification (Tasqiyah): giving in charity the tiny share of potentially contaminated income, without expecting any reward. This process, based on the 5% threshold of illicit income defined by AAOIFI, enables platforms like Namlora to remain compliant while using traditional banking infrastructures.

Dealing with the inevitable: purification (Tasqiyah) in the face of indirect exposure

L’exposition indirecte : une contamination critique systémique

Riba is making inroads everywhere, even in legitimate businesses. In Europe, the PSD2 requires fintechs to deposit customer funds with traditional banks. However, the latter generate interest, linking fintech revenues to the Riba. This is not a choice, but a structural reality: the global financial system is based on interest, even for ethical players.

Tasqiyah: an ethical solution for purifying income

Tasqiyah is a pragmatic response. It consists in estimating the tiny part of one's income linked to systemic Riba (such as the interest generated by bank funds), then giving this sum in charity, without expecting any spiritual counterpart. It's a responsible way to act in an imperfect system. For Samira, this could mean purifying the interest generated by her savings account, however small.

An often-quoted benchmark is the 5% threshold of illicit revenues used by AAOIFI for screening actions. This figure is not a strict rule, but a benchmark for acting in good conscience. For example, an individual receiving interest via a classic account would have to donate 5% of these earnings to charity.

To find out more about purification in halal investing, check out Namlora's guide to purifying stock market earnings. A solution for those who, like Samira, are looking to combine modernity and values.

Towards a paradigm shift: ethics at the heart of finance

Riba is not just a religious prohibition, but a structural financial anomaly. By setting a guaranteed return on capital, it disconnects finance from the real economy, deepening inequalities and instabilities. Institutions like AAOIFI and Majmaʿ al-Fiqh al-Islami are fighting to frame this system, demanding real economic substance from Islamic financial products.

Sukuk, which is supposed to represent shares in tangible assets, and Murabaha, which is often misused as a disguised loan, illustrate what is at stake: preventing Islamic finance from becoming a mere carbon copy of the conventional model. Even purification (Tasqiyah), which provides for the income from systemic Riba to be donated to charity, underlines the fact that the challenge goes beyond business practices alone.

This critique opens up a radical path: rethinking finance around the sharing of risk and the creation of tangible value. Namlora embodies this vision, building an ecosystem where transparency, justice and responsibility guide every investment. By linking faith and economics, this model aims to restore trust between savers, entrepreneurs and consumers.

As one academic study points out, this approach offers a better alternative to conventional financial products. By putting people and society back at the heart of exchanges, it outlines the contours ofa fairer capitalism, where profit serves sustainability rather than speculation.

Criticism of Riba reveals a financial anomaly with far-reaching social consequences. Beyond the religious prohibition, it calls for a rethinking of finance based on the sharing of risk and real value. Namlora embodies this vision, combining ethics and innovation for a just system, where faith and responsibility guide the economy. Let' s build this alternative together.

FAQ

Why is riba forbidden?

Riba is forbidden because it creates economic injustice by rewarding capital without effort or risk sharing. Unlike other investors who earn according to results (such as dividends), the interest-bearing lender always profits, even if the borrower's business fails. This system destabilizes the economy by transferring risk to the weakest and concentrating wealth. It's a practice as old as time, condemned both by the Koran and by thinkers such as Aristotle, who considered it "unnatural".

What does the Koran say about Riba?

The Qur'an strongly condemns riba in Sura Al-Baqarah (2:275-279), comparing it to a spiritual disease that leads away from justice. It clearly distinguishes trade (permissible) from interest (forbidden), since trade implies a sharing of risk and profit, whereas riba profits without any real contribution. The verses also emphasize that persisting in riba after being warned leads to severe punishment, showing the importance of this prohibition for social equilibrium.

Does Allah forgive Riba?

Yes, Allah forgives all sins, including riba, if we sincerely repent and abandon this practice. The Qur'an (2:275) offers a way out: "Whoever abstains after being warned will have his past deeds forgiven". However, it insists on the need to break completely with riba, as persisting despite divine warning is a grave sin. Repentance also includes purification (tasqiyah) by giving illicit gains in charity without expecting any reward.

How to get rid of riba money?

If you receive interest by accident, the solution is tasqiyah (purification). You must estimate the proportion of your income linked to riba (for example, via traditional banks) and give it to charity without expecting any gratitude. AAOIFI sometimes recommends a threshold of 5% to guide this calculation. This is not a punishment, but a way of staying in line with your values, even in an imperfect system.

Why is riba bad?

Riba is a poison for the economy and society. It encourages speculation to the detriment of productive projects, widens inequalities (poor people pay more for credit) and makes crises more violent, as in 2008. It transforms money into a money-making machine, with no link to work or the creation of value, which exhausts the real economy. Like a tumor, it sucks up resources to fatten the richest.

What's the difference between ARB and Riba?

Arbitrage (ARB) is a lawful profit earned by analyzing price differentials between markets, while riba is a guaranteed gain on a loan, independent of results. Arbitrage respects the principles of trade (shared risk, effort), while riba profits without any real input. It's like the difference between buying a good in order to resell it (permitted) and charging extra just for lending money (forbidden). The Koran authorizes trade but clearly condemns riba.

Is riba a serious sin in Islam?

Yes, riba is classified as a "major sin" (kabair) in several hadiths. The Koran (2:279) warns against its persistence, comparing usurers to those "haunted by the devil". Muslim scholars, such as Ibn Hazm, insist on its categorical prohibition, as it destroys social trust and fosters injustice. It is a collective sin that affects society as a whole, not just the individual.

What's the worst injustice in the Koran?

The Koran (4:160-161) refers to the injustice of the "rabbis" who transformed licit practices into forbidden ones in order to control people, but the worst injustice remains riba. It is described as an economic "tumor" that destroys natural balances. In the long term, it deepens inequalities, makes life more expensive for the poor and weakens states (like Ecuador, with 80% of its budget in debt). It's a systemic injustice, not just an individual one.

Is interest worse than zina?

This is a complex comparison, as both are serious, but in different areas. Hadiths classify riba as "great turpitudes" (fawaheish), but zina touches on moral purity and family ties. However, the Koran (4:161) accuses past communities of having been destroyed by riba, and economists such as Aristotle saw it as "the worst of transactions". In terms of collective impact, riba can be seen as more devastating, as it affects whole systems, not just the individual.