<meta name="google-site-verification" content="0S72xkYcSqqt100ZuIzn_Zif1zL8vIvcXUmc5Tjo10o" />

Key points to remember: Riba, the mainstay of the modern financial system, mechanically generates inflation and inequality through its debt-based currency. While 1% of the population holds as much as 50%, Islamic finance offers a solution through the sharing of risks and real assets, restoring a fair and sustainable balance.

Do you have the feeling that your money is losing value without you understanding why? Inflation, the real tax on the poor, is no accident: it stems from a monetary system rooted in Riba, the guaranteed interest that destabilizes the economy. Every euro put aside suffers the erosion of its purchasing power, while the better-off protect their assets with real assets such as real estate or gold. In this article, we explore how this mechanism deepens inequalities, transforms debt into an engine of poverty, and reveals concrete alternatives, such as Islamic finance, which redistributes risk and reconnects money to the real economy for a fairer future.

Contents

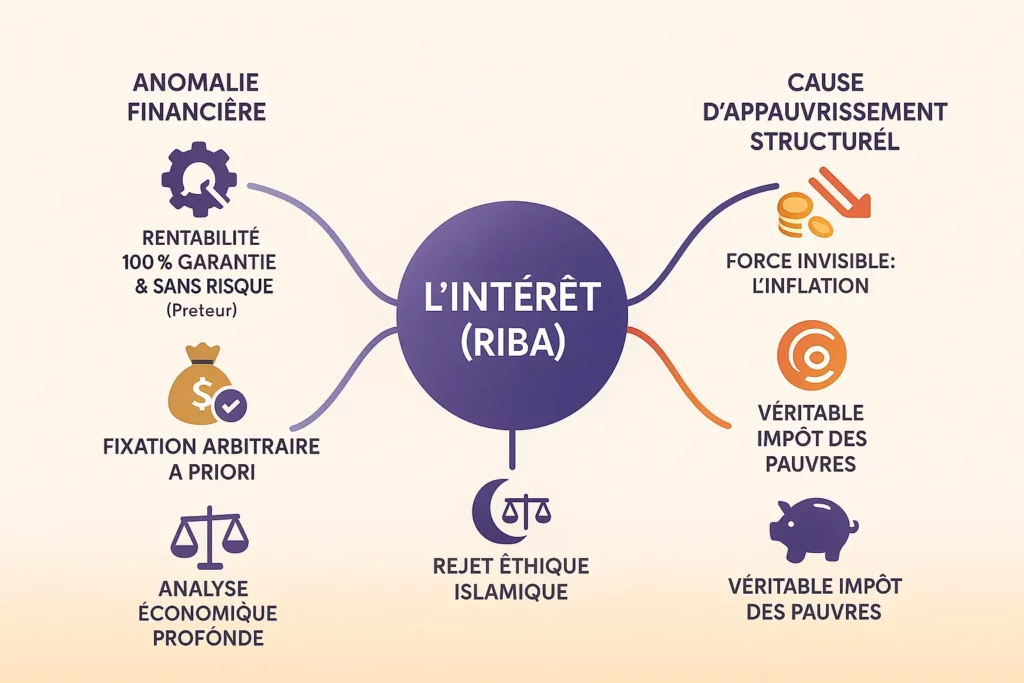

Interest (Riba): a financial anomaly at the heart of our economies

Imagine a world where capital generates a guaranteed return, without effort or risk. This utopian scenario sums up the very essence of bank interest. Why is this mechanism, so central to our monetary systems, considered a distortion?

Bank interest, or Riba in Islamic finance, represents a rare exception in the financial world: a guaranteed 100% return for the capital holder, with no involvement in value creation. Unlike dividends or entrepreneurial profits, this remuneration applies a priori, even before the economic process generates wealth. This anticipation creates a fundamental distortion.

Islamic criticism of Riba goes beyond the religious framework to point to a structural flaw: by arbitrarily fixing the value of monetary time, this system subordinates the real economy to finance. By creating money from interest-bearing debts, banks activate a mechanical inflationary mechanism. This phenomenon acts like an invisible tax, levied first and foremost on vulnerable savers. Discover how inflation progressively destroys purchasing power. According to the Cantillon effect, the first beneficiaries of this new money benefit from unchanged prices, while ordinary households suffer higher costs for which there is no immediate compensation.

Unlike Islamic models, where the return on capital depends ex-post on actual results, Riba reverses sound economic logic. Capital alone produces nothing: a bar of gold left for a thousand years remains a bar of gold. Yet interest rewards this simple storage, breaking the link between effort and reward.

This structural anomaly generates two major perverse effects: on the one hand, it concentrates wealth in favor of those who receive the new money first (the Cantillon effect); on the other, it amplifies economic cycles through its procyclical nature. The system thus becomes intrinsically unstable, creating chasms between social classes.

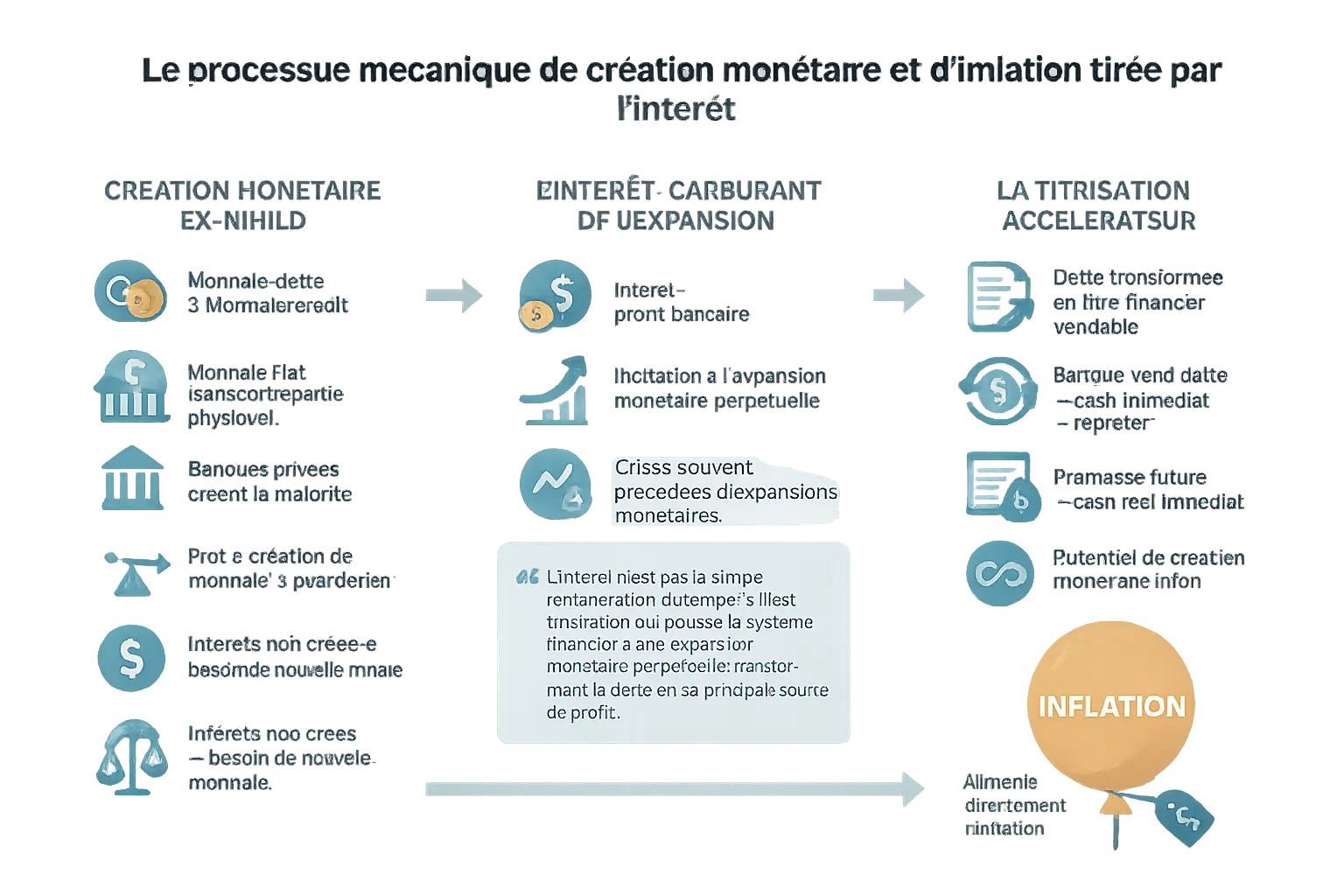

Riba: the mechanical engine of money creation and inflation

Ex-nihilo money creation by private banks

Our monetary system is based on the creation of fiat money, with no physical counterpart, mainly generated by private commercial banks. When a bank makes a loan, it doesn't draw on existing deposits, but creates money "out of thin air" by crediting the borrower's account. This process is reminiscent of the saying "money calls money", where debt becomes the very source of money.

This mechanism poses a paradox: the loan capital is destroyed on repayment, but interest has never been created. This structure generates a perpetual need for new loans to cover previous debts. Imagine a gardener having to prune a plant faster than it grows: the monetary system follows this pattern, where banks must constantly inject credit to avoid collapse. If economic growth doesn't keep pace, the gap widens, fuelling inflation as a debt with no real basis.

Interest: the fuel of monetary expansion

Interest is not simply the remuneration of time; it is the incentive that drives the financial system to perpetual monetary expansion, transforming debt into its main source of profit.

Interest is the banks' guaranteed profit, encouraging them to lend more and more. This mechanism transforms credit into a veritable "business", fuelling deregulated money creation. Without interest, the system would lose its main engine of expansion. Maurice Allais, winner of the 1988 Nobel Prize in Economics, pointed out that this model leads to inevitable speculative bubbles: "trees don't grow to the sky", he warned, illustrating the systemic collapse of inflationary excesses.

Securitization: the gas pedal to infinite money creation

Securitization transforms debt into marketable assets. A bank assigning a loan to a specific legal entity receives immediate liquidity, enabling it to instantly renew its lending activity. This technique converts a promise of future repayment into an immediate present cash flow, increasing money creation capacity tenfold.

Unlike the traditional system, which limits money creation by a factor of 10, securitization theoretically makes this capacity infinite. By transforming each euro of reserves into leverage to generate hundreds of euros of credit, this mechanism exponentially amplifies inflation, acting as an uncontrollable financial gas pedal. Like a snowball rolling down an endless slope, securitization fuels an inflationary cycle in which the value of money erodes inexorably, affecting the most vulnerable households first.

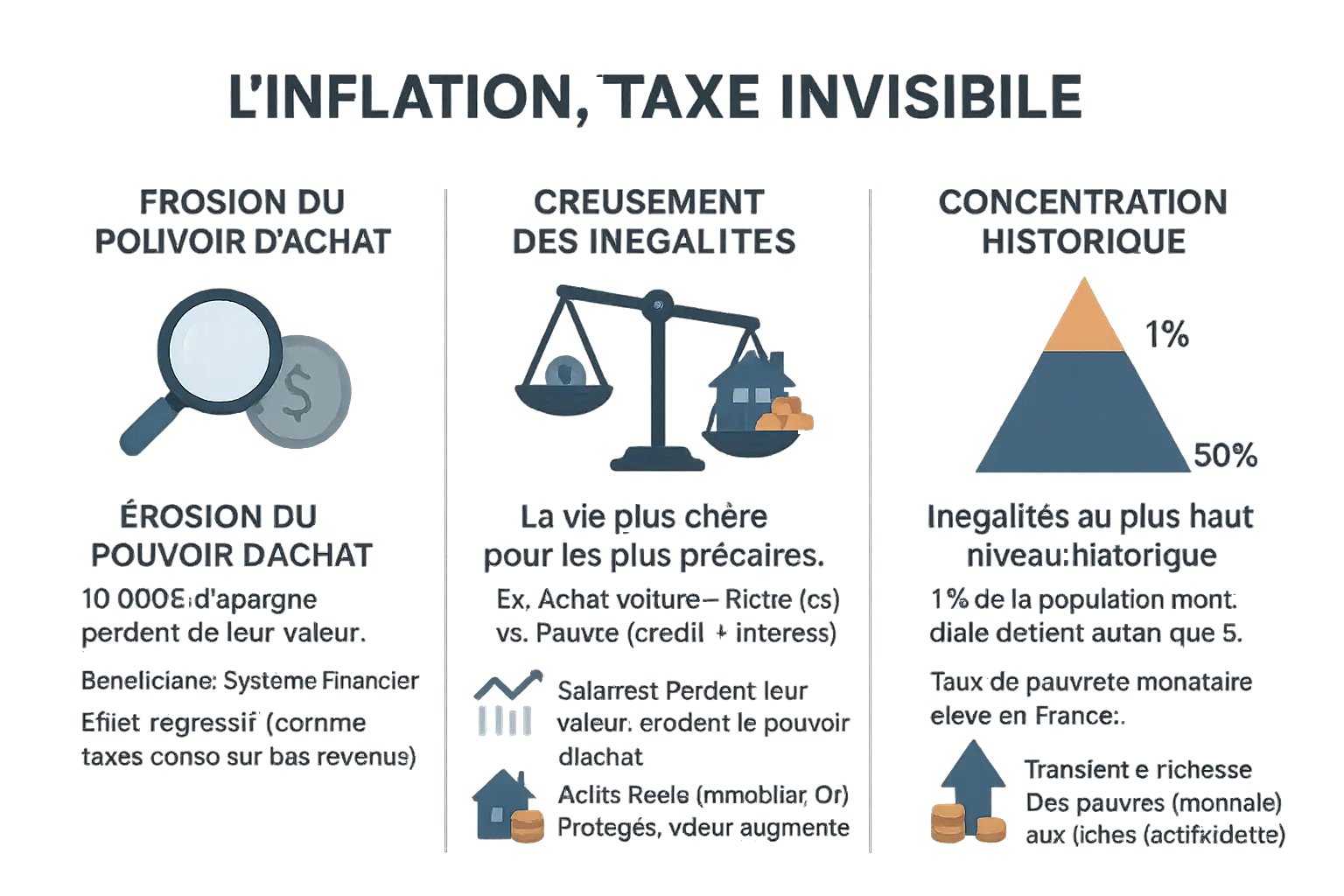

Inflation: the hidden tax that impoverishes the most vulnerable

Erosion of purchasing power: an invisible drain on savings

Imagine you invested €10,000 in 2018. Today, this sum has lost 30 to 40% of its purchase value. This phenomenon is not insignificant.

Inflation acts as a hidden tax that applies to everyone, without distinction. It allows the financial system to take a share of your savings without you being aware of it.

This mechanism primarily benefits the financial system behind money creation. It's an indirect source of profit for money creators.

Like indirect taxes on consumer goods, inflation is particularly regressive. It weighs more heavily on low-income households. According to the World Bank, this type of levy has a greater impact on those who have no significant savings or assets to protect them from monetary depreciation.

How Riba and inflation widen inequalities

The Riba-based system makes life more expensive for the most vulnerable. Let's take a concrete example: a new car costs €30,000. For a well-off person, this is a one-off cost. For a poor person forced to take out a loan, the same item will cost €35,000 to €40,000.

Inflation affects different social categories in different ways:

- Impact on wages: Wage income, paid in depreciated currency, loses its real value.

- Protecting real assets: Unlike real estate or precious metals, money loses value.

- Result: the system mechanically transfers wealth from holders of cash to those with productive assets.

This dynamic explains why real assets, such as gold and real estate, provide effective protection against currency erosion.

A historic concentration of wealth

The current monetary system is widening gaps unprecedented in human history. Today, 1% of the world's population has as much wealth as the poorest 50%.

This concentration is reflected in national statistics. According to INSEE, despite social policies, the monetary poverty rate in France remains significant. Low-income households are more affected by price rises in food, energy and transport, items which account for a significant proportion of their expenditure.

The effects of this inequality are felt in access to healthcare and education. Precarious families often postpone medical consultations or forego vocational training, further widening the social gap.

An unstable system out of touch with the real economy

Behind the apparent stability of the modern financial system lies a logic that feeds instability. By structuring the economy around debt, Riba not only creates inequalities, it also disrupts the mechanisms of growth. This system, based on guaranteed returns on capital, encourages risky behavior and distances finance from its primary role: serving the real economy.

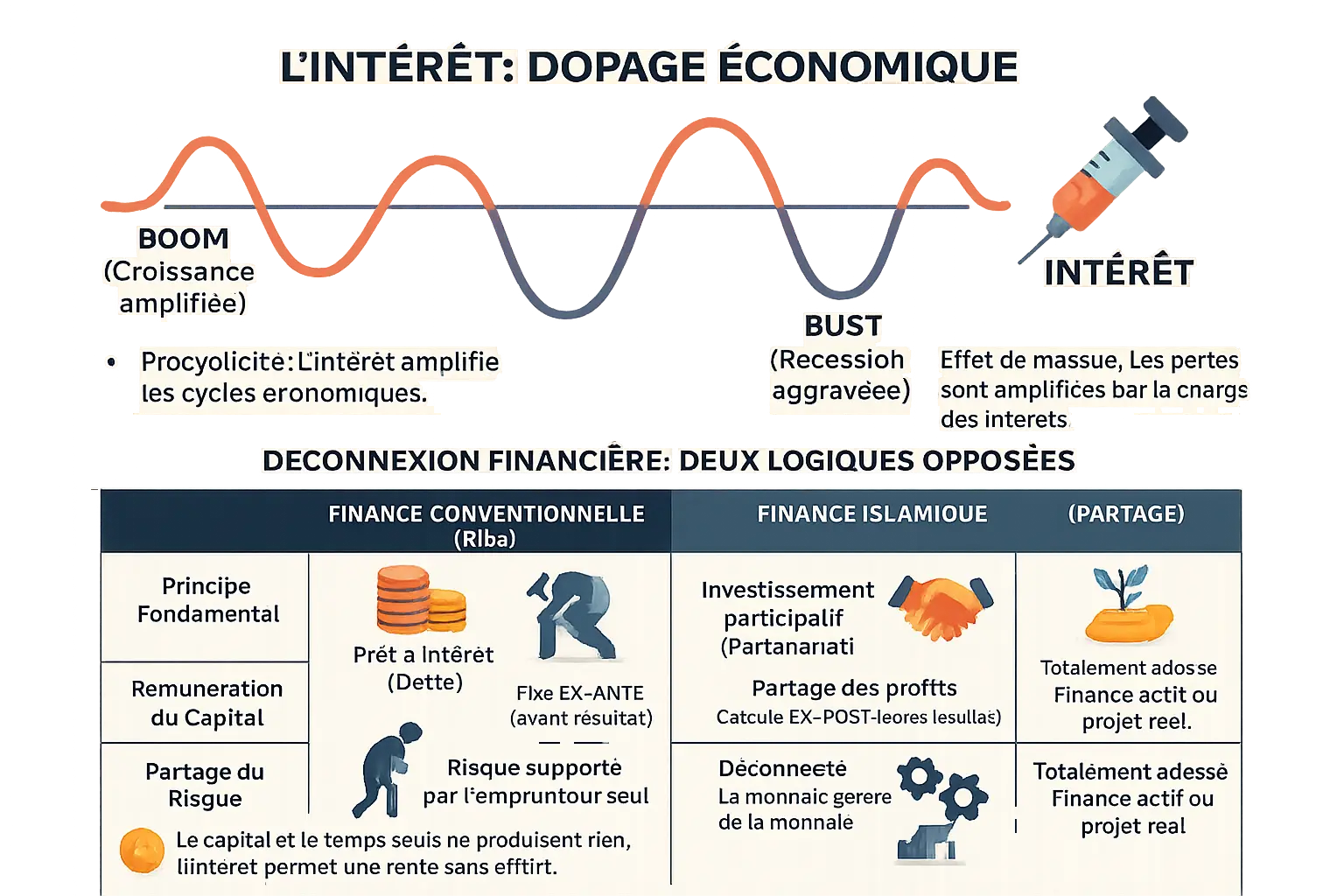

Interest, a "doping" that amplifies economic crises

Riba's effect on the economy resembles that of sports doping: boosted performance in times of growth, but devastating side-effects in times of crisis. By facilitating credit, interest stimulates investment, but deepens the troughs in the event of a downturn. This procyclical mechanism transforms initial shocks into major crises. The 2008 crisis illustrates this phenomenon: leverage in real estate, via variable-rate loans, triggered foreclosures when interest rates rose again. This "sledgehammer" dynamic is explained by the rigidity of financial charges: a company in difficulty has to repay its debts, worsening its situation, while banks tighten credit, fuelling the depressive spiral.

Financial disconnection: when rent replaces production

Riba breaks the link between capital and value creation by imposing ex-ante remuneration, decided before results. In contrast, Islamic profit-sharing follows an ex-post logic, based on concrete results. Let's compare these two models:

| Features | Conventional finance (based on Riba) | Islamic Finance (based on Sharing) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental principle | Interest-bearing loan (Debt) | Participatory investment (Partnership) |

| Return on capital | Interest (Riba) - Fixed ex-ante | Profit sharing - Calculated ex-post |

| Risk sharing | Risk borne by the borrower alone | Risk shared between investor and entrepreneur |

| Link to the real economy | Disconnected (money generates money) | Fully backed (money finances a real asset) |

This ethical divergence leads to a practical difference: in the conventional system, capital generates money on its own, whereas Islamic finance links value to real exchange. By sharing profits and losses, it reintroduces precaution and responsibility into decision-making, re-establishing a logic in which returns depend on the real economy, not on an autonomous monetary mechanism.

Islamic finance: an alternative for a fairer, more stable system

Les piliers d’une économie saine : partage des risques et adossement au réel

Islamic finance embodies an economic vision based on risk sharing, as opposed to the Riba-based system. It links capital and labor inseparably through mechanisms such as Mudaraba (a partnership in which the investor provides the funds and the entrepreneur the expertise) and Musharaka (co-investment with proportional sharing of profits and losses). Just as a gardener shares his crops with a partner rather than receiving a fixed rent, these contracts create economic solidarity.

The concept ofasset-backed finance anchors every transaction in reality: physical goods, concrete services, tangible projects. This approach prohibits the creation of money ex-nihilo, avoiding empty speculation. Money becomes a simple tool of exchange, not a commodity generating profits in its own right.

Namlora offers solutions for investing responsibly and ethicallyby aligning your spiritual values with your financial choices. Our tools enable you to support economic initiatives that respect the principles of Islamic finance, strengthening both your wealth and your social contribution.

The challenge of purification(Tasqiyah) in a world dominated by self-interest

Even Islamic fintechs sometimes have to use traditional banking infrastructures for regulatory reasons (e.g. PSD2). It's like sailing with a gasoline engine in tow - a necessary compromise to operate in a global system that 's still imperfect.

Purification is an ethical commitment to cleanse one's investments of any impurities linked to interest, recognizing that perfection is an ideal but integrity is a duty.

Tasqiyah requires income indirectly linked to Riba to be donated to social causes, even in small proportions. This process involves a meticulous calculation of financial flows to identify the amounts to be redistributed. AAOIFI sometimes refers to a threshold of 5% of illicit income as a technical benchmark, reminding us that integrity remains accessible to those who sincerely seek it. This practice is part of a broader approach that includes Zakat (compulsory almsgiving) and Sadaqa (voluntary donations), reinforcing the social commitment of Muslim investors.

Building a fairer financial future: a societal choice

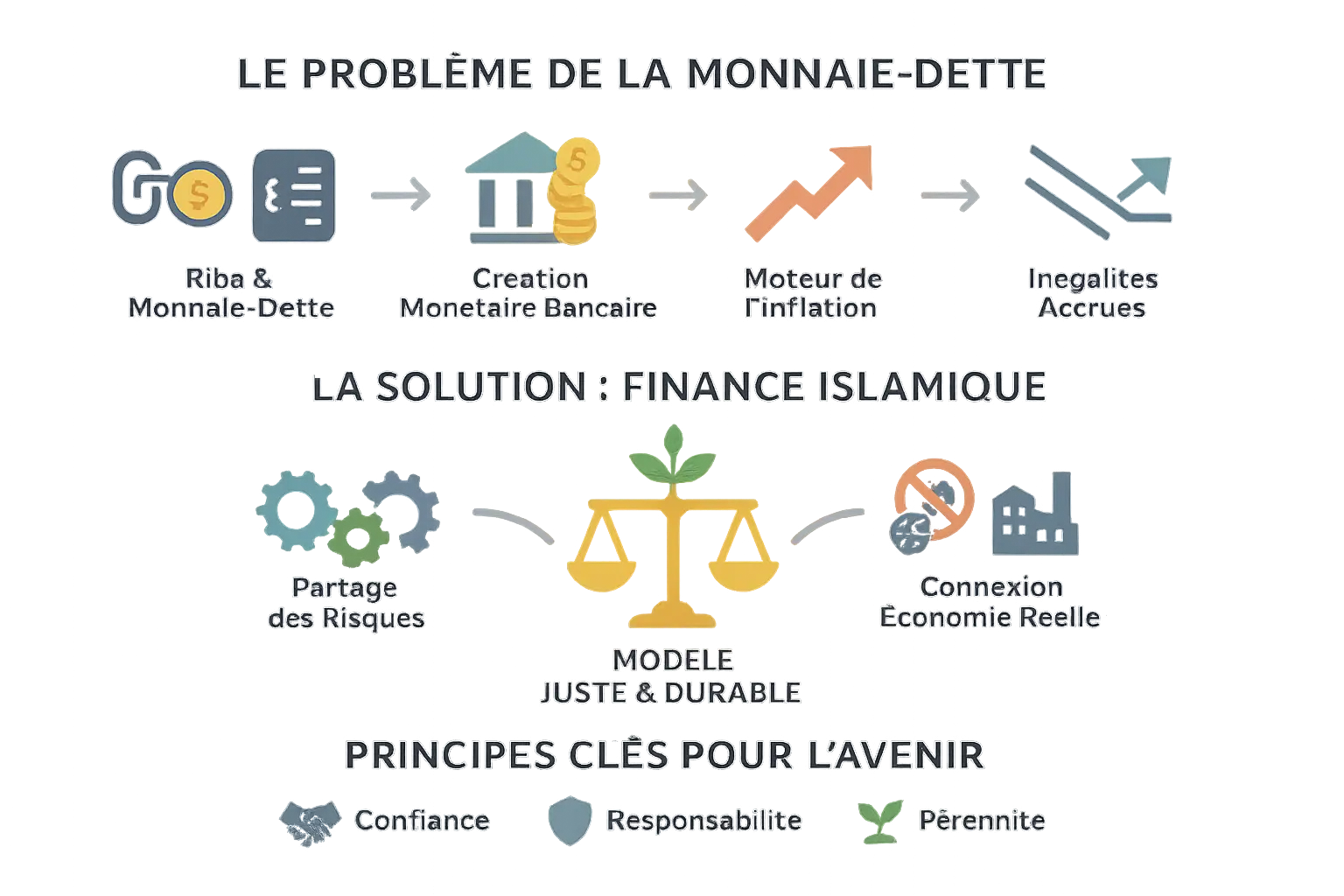

The current monetary system, rooted in the principle of Riba, creates a vicious circle. By allowing money to be created out of debt, it mechanically feeds inflation, the "invisible tax" that hits the most vulnerable hardest. Every euro earned depreciates, every loan to meet essential needs becomes an additional burden. Meanwhile, wealth is concentrated, widening the gaps to unprecedented levels.

Faced with this reality, Islamic finance doesn't just offer a religious alternative. It proposes a fundamentally different model, rooted in equity and stability. By forbidding Riba and demanding that it be anchored in the real economy, it re-establishes logic: money does not produce money on its own, it must serve a concrete project. Sharing profits and losses reintroduces solidarity into financial exchanges.

Namlora embodies this vision. By uniting investors, entrepreneurs and consumers around ethical values, our halal ecosystem restores meaning to the economy. Our aim is not just to generate returns, but to cultivate trust, empower stakeholders and build a sustainable future. Because a fair financial system is not a utopia: it's a choice, made by concrete, moment-by-moment decisions.

By orienting your savings and investment choices towards these principles, you're not just protecting your capital. You're taking part in a profound change that puts people back at the heart of finance. The future isn't written - it's being built, with each investment act in line with your convictions.

La finance islamique propose un modèle juste et stable, rompant avec le Riba pour relier finance et économie réelle. En partageant risques et profits, elle combat l’inflation injuste et les inégalités. Chaque choix d’investissement éthique trace le chemin vers un système plus responsable. Ensemble, construisons une économie où la confiance et la pérennité guident chaque décision.

FAQ

Les riches paient-ils moins d’impôts que les pauvres ?

En réalité, le système fiscal traditionnel est loin d’être équitable. Si les riches paient en apparence des impôts plus élevés en montant absolu, l’inflation agit comme une « taxe cachée » qui frappe proportionnellement plus les ménages modestes. En effet, l’inflation réduit le pouvoir d’achat de la monnaie, touchant principalement ceux qui détiennent peu d’actifs réels (comme l’immobilier ou l’or). Les riches, eux, ont tendance à investir dans ces actifs dont la valeur augmente avec l’inflation, les protégeant ainsi de sa morsure.

Imaginez un arbre : les racines (les pauvres) sont exposées à l’érosion du sol (l’inflation), tandis que le tronc et les branches (les riches) grandissent grâce à la lumière (les actifs réels). Cette dynamique inégale est renforcée par le système de la monnaie-dette basé sur le Riba, où l’intérêt garantit un profit sans risque à ceux qui contrôlent la création monétaire. Le système agit donc comme un filtre inversé, transférant de la valeur du bas vers le haut.

Comment l’inflation affecte-t-elle les pauvres ?

Pour les ménages précaires, l’inflation est un fardeau silencieux mais puissant. Elle diminue la valeur de leurs salaires et de leurs épargnes, sans qu’ils n’aient leur mot à dire. Prenez le quotidien d’un ouvrier : il dépense une grande partie de ses revenus en biens essentiels (nourriture, logement, énergie), dont les prix montent plus vite que l’inflation moyenne. Son épargne, souvent en cash, perd de sa valeur, tandis que les riches investissent dans des actifs qui s’apprécient avec l’inflation.

Imaginez un équilibre fragile où chaque euro gagné vaut de moins en moins. C’est comme si, chaque mois, votre salaire était un peu plus léger, sans contrepartie. Le Riba, en alimentant la création monétaire, est la cause mécanique de ce déséquilibre. Les pauvres paient donc le prix d’un système qui favorise ceux qui en sont les créateurs, transformant l’inflation en un impôt des pauvres.

Qui s’enrichit pendant l’inflation ?

Les principaux bénéficiaires de l’inflation sont les créateurs du système monétaire : les banques et les acteurs financiers. Grâce au Riba, chaque prêt génère de l’argent neuf, créant un profit garanti pour les prêteurs. En parallèle, les riches, qui investissent massivement dans des actifs réels (immobilier, métaux précieux), voient la valeur de leurs avoirs croître avec l’inflation, tandis que leur dette réelle diminue.

Prenez un exemple simple : un propriétaire immobilier avec un prêt profite d’une baisse de la valeur de sa dette, tandis que son bien s’apprécie. Ce mécanisme est comme un double avantage : gagner sur la dette et sur l’actif. Les pauvres, eux, n’ont souvent pas cette possibilité. Le Riba, en permettant cette dynamique, creuse les inégalités, enrichissant ceux qui maîtrisent le jeu de la monnaie-dette.

L’inflation est-elle un impôt régressif ?

Oui, l’inflation est souvent comparée à un impôt régressif, car elle prélève davantage les ménages modestes. Contrairement à un impôt progressif (où les riches paient plus en proportion), l’inflation affecte tout le monde de la même manière, mais son impact est plus lourd pour ceux qui ont peu. Les pauvres dépensent une part plus grande de leurs revenus en dépenses contraintes (logement, alimentation), des postes fortement impactés par l’inflation.

C’est comme un impôt invisible : personne ne le voit, mais chacun en subit les effets. Le Riba, en incitant les banques à une expansion monétaire continue, est le moteur de cette ponction. Ce système redistribue mécaniquement de la valeur des ménages vers les créateurs de monnaie, transformant l’inflation en un outil d’injustice économique systémique.

Pourquoi les pauvres paient-ils plus d’impôts que les riches ?

Les pauvres ne paient pas plus d’impôts en apparence, mais en réalité, l’inflation agit comme un impôt déguisé qui les frappe de manière disproportionnée. Leurs salaires, versés en monnaie fiduciaire, perdent de leur valeur année après année, tandis que les riches investissent dans des actifs réels (comme l’immobilier) protégés de cette érosion. De plus, les pauvres, souvent contraints d’emprunter pour des besoins essentiels, paient des intérêts supplémentaires qui alourdissent leur charge.

C’est un peu comme si tout le monde portait le même manteau, mais que seuls les plus vulnérables sentaient le froid. Le Riba, en rendant la vie plus chère via l’inflation et les prêts, agit comme une double peine : les pauvres paient d’une part des intérêt directs sur leurs emprunts et d’autre part une part invisible d’inflation, sans bénéficier des protections dont disposent les plus aisés.

Quel salaire pour être considéré comme pauvre ?

En France, le seuil de pauvreté est fixé à 60 % du revenu médian, soit environ 1 200 € nets mensuels pour une personne seule en 2023. Ce seuil traduit une réalité : les ménages sous ce seuil ont des difficultés à couvrir leurs besoins de base (logement, alimentation, soins). L’inflation frappe ces ménages en premier, car une grande partie de leurs dépenses concerne des biens essentiels dont les prix augmentent souvent plus vite que l’inflation générale.

Le Riba, en alimentant l’inflation, aggrave cette situation. Un travailleur au SMIC, par exemple, voit son épargne et son salaire perdre de leur pouvoir d’achat, tandis qu’un investisseur a les moyens de se protéger en diversifiant ses actifs. Ce mécanisme transforme l’inflation en une machine à creuser les écarts, rendant la pauvreté plus persistante

L’inflation est-elle meilleure pour les riches ou pour les pauvres ?

L’inflation profite principalement aux riches, qui disposent d’outils pour s’en protéger. En investissant dans des actifs réels (comme l’immobilier ou les métaux précieux), ils préservent leur capital. En revanche, les pauvres, qui détiennent plus d’argent liquide et dépensent une grande partie de leurs revenus en dépenses fixes, subissent une double ponction : une baisse de leur pouvoir d’achat et un accès plus difficile aux prêts qui pourraient les aider à investir.

Le Riba est au cœur de ce déséquilibre. En incitant les banques à créer toujours plus de monnaie-dette, il génère de l’inflation, un phénomène qui favorise les détenteurs de capital au détriment des travailleurs. C’est un peu comme cultiver un jardin : les riches récoltent les fruits de la croissance, tandis que les pauvres doivent se battre contre les mauvaises herbes de l’inflation.

Qui souffre le plus de l’inflation ?

Les ménages précaires sont les plus touchés par l’inflation. Leur budget est tendu vers les dépenses essentielles (logement, alimentation, énergie), des postes sensibles à la hausse des prix. En parallèle, leur épargne, souvent en cash ou à faible rendement, perd de sa valeur. Les retraités, les chômeurs ou les travailleurs à temps partiel, dont les revenus sont stables ou limités, ressentent encore plus durement ces effets.

Le Riba, en amplifiant l’inflation via un système de monnaie-dette, aggrave cette vulnérabilité. Pour les plus fragiles, c’est comme un orage économique : sans filet, chaque goutte (chaque euro perdu de pouvoir d’achat) est une épreuve. Les riches, eux, ont des parapluies solides, comme les actifs réels ou les investissements protégés de l’érosion monétaire.

Pourquoi perd-on de l’argent avec l’inflation ?

L’inflation érode la valeur de la monnaie : avec le temps, un euro achète moins de biens et services. Cela touche particulièrement les épargnants, dont le capital perd du terrain, et les travailleurs, dont les salaires, bien que parfois indexés, ne suivent pas toujours le rythme des prix. Cette perte n’est pas un simple risque, mais un mécanisme structurel alimenté par le système basé sur le Riba.

En fait, l’inflation est une redistribution silencieuse : elle transfère de la richesse des épargnants vers les créateurs de monnaie (les banques) et les détenteurs d’actifs réels (les riches). Le Riba, en incitant à la création monétaire, est le moteur de cette perte collective. C’est comme un filet invisible qui laisse filer la valeur de vos économies, au profit de ceux qui contrôlent les vannes de la création financière.