<meta name="google-site-verification" content="0S72xkYcSqqt100ZuIzn_Zif1zL8vIvcXUmc5Tjo10o" />

Key points to remember: The materialistic paradigm, based on profit and growth, ignores social justice and sustainability. By valuing only the quantifiable, it deepens inequalities and threatens the environment. Understanding this mechanism is key to reorienting the economy towards the ethical and human values essential to a sustainable society.

Have you ever noticed that, despite unbridled growth and the accumulation of wealth, there's a growing gulf between social classes? The materialistic paradigm at the heart of capitalism reduces human beings to an adjustment variable and transforms justice into a mere accessory to the markets. Behind its opaque mechanisms - Riba, underhand inflation and concentration of power - lies a system that values the profit-producing individual to the detriment of human beings and the planet. Discover how this dehumanizing logic shapes your daily life, deepens inequalities and threatens our collective future, by challenging everything you know about economics.

Contents

The materialist paradigm: what really drives our global economy?

For decades, the same invisible logic has guided global economic decisions. Behind market fluctuations, crises and trends, a pattern repeats itself: does the materialistic paradigm really dominate our system?

This model is based on a simple idea: value can only be measured by tangible indicators. Profit, production, GDP - these figures dictate policies, investments and even our individual choices. Whether we call it "capitalism", "market economy" or some other term, the foundation remains the same: a vision of the world in which the material takes precedence over the intangible.

The major economic schools - classical, Keynesian, Marxist - share this foundation. Yet their differences are clear when it comes to optimizing this system. Like a compass always pointing towards profit, this paradigm ignores human, social and spiritual dimensions. What becomes of justice, equity or sustainability in a model that reduces wealth to the simple calculation of growth?

Behind this approach lies a complex reality: a network of mechanisms that shape our daily lives. In the following lines, we explore how this logic, centered on capital and quantity, redefines our collective priorities and digs fissures in society.

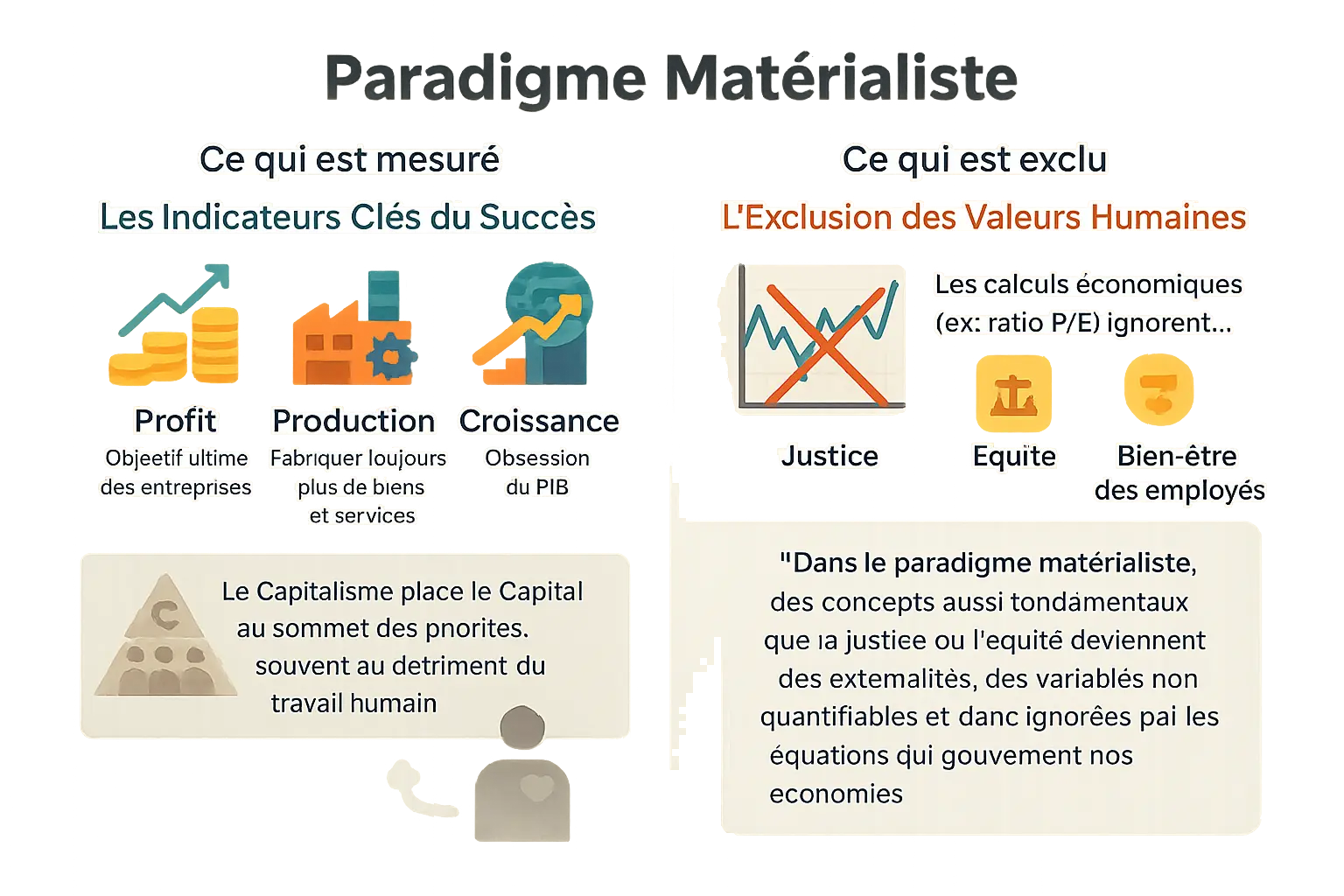

Defining the materialist paradigm: the reign of material indicators

The dominant materialist paradigm places capital at the heart of the economy. This system, known as capitalism, evaluates success solely on the basis of tangible criteria, transforming human resources into a mere adjustment variable. This model is based on the idea that wealth is measured bymaterial accumulation, obscuring the ethical and social dimensions of the economy.

Key success indicators: profit, production and growth

Performance is assessed through three pillars:

- Profit: the driving force behind strategic decisions, guiding economic policies despite social or ecological consequences. For example, a company may lay off employees to improve short-term profitability, without integrating the human cost of these decisions.

- Production: continuous manufacture of goods, prioritized despite overproduction and waste. The fashion industry expresses this phenomenon with disposable seasonal collections that saturate markets and pollute ecosystems.

- Growth: GDP reduces national wealth to a single figure, concealing inequalities and ecological degradation. A country can post positive growth while its natural resources are depleting or income disparities are widening.

The term capitalism reflects this hierarchy, in which capital takes precedence over other resources. Yet capital is nothing more than an accumulation of human labor, a reality often overlooked in economic calculations. This discrepancy reinforces a system in which the human element is diluted by abstract mechanisms of financial valuation.

Excluding human values from economic equations

"In the materialist paradigm, concepts like justice or equity become externalities ignored by economic models."

The example of the Price/Earnings ratio (P/E ratio) illustrates this disconnect. This tool evaluates the time required to recover an investment without taking into account its social or environmental impact. A polluting company can thus boast an attractive P/E ratio while degrading local ecosystems. Philosophical liberalism reinforces this discrepancy by promoting individual egoism as the driving force behind markets, neglecting the collective dimension of the economy. This framework justifies decisions that are financially rational but potentially destructive in human terms. The notion of negative externalities, such as pollution, remains on the periphery of calculations, reflecting a logic in which social and ecological costs are never internalized by economic players.

The social consequences: a company at the service of finance

The inversion of the social pyramid and the concentration of wealth

Inversion of the pyramid describes a system in which a minority holds as much wealth as the poorest half. This model reinforces historic levels of inequality through rent - a mechanism that remunerates capital without effort or risk. Wealth grows exponentially for the few, while the majority stagnates, concentrating economic power and distancing society from its ethical foundations.

Dehumanizing work and rewarding the unproductive

Dehumanization of work: human beings are reduced to "labor" in economic equations, an adjustment variable to maximize profit, ignoring the dignity and skills of essential professions.

Can you see the paradox? Financial professions with low added value are better paid than manufacturing or care jobs.

| Economic player | Real added value for the company | Typical pay levels in the system |

|---|---|---|

| Producer of essential goods (e.g. farmer, craftsman) | High (food, useful items) | Low to medium |

| Service sector workers (e.g. caregivers, teachers) | High (health, education, well-being) | Medium |

| The financial speculator (e.g. high-frequency trader) | Low or nil (wealth transfer) | Very high |

This model attracts the best minds to financial professions with little tangible impact. Are the baker who feeds or the nurse who cares valued at their fair price?

In our societies, work has become the pillar of social identity. Losing one's job often means losing status and relationships, under constant pressure to prove one's worth through productivity.

By measuring success by profit, haven't we forgotten true value? Behind the numbers lie lives that markets fail to grasp. The Namlora project embodies a desire to put spirituality, transparency and justice back at the heart of economic exchanges, for a fairer, more humane model.

Inflation and interest-bearing loans (Riba): the driving force behind instability

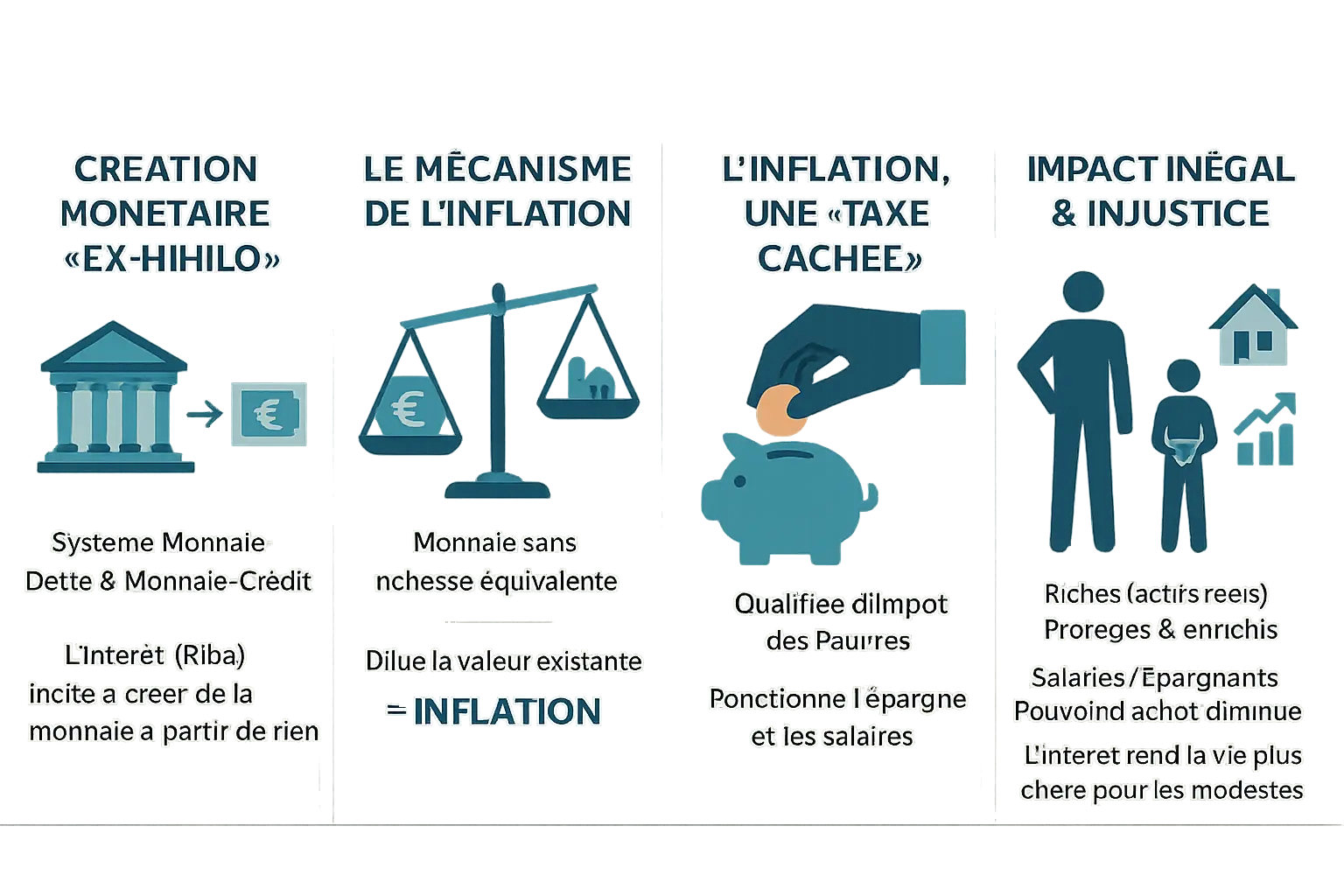

The mechanics of inflation: "ex-nihilo" money creation

Today's economic system is based on debt and credit money, generated by commercial banks through loans. This process, known as "ex-nihilo" money creation, means that banks produce money by simple bookkeeping entry, without the need for prior savings.

Interest (Riba) stimulates this machine. It pushes institutions to grant credit, amplifying the money supply without any guarantee of real wealth. Every euro lent is added to the money supply, devaluing existing banknotes and generating inflation. This phenomenon erodes the value of money, making consumer goods increasingly expensive. Post-2008 stimulus policies, for example, based on money creation, have exacerbated this drift.

Inflation, a "hidden tax" that burdens the poorest

Inflation acts as a tax on the poor. It reduces the purchasing power of low-income households, who depend on wages and savings in conventional currencies. Their budgets are hit by the rise in essential goods (food, energy), often faster than general inflation. Even indexing the minimum wage to the CPI does not offset this impact, as critical expenses weigh more heavily in their consumption basket.

Conversely, the wealthiest are sheltering in real assets (real estate, commodities) whose value rises with inflation. Their debt, repaid in devalued euros, is mechanically reduced. A vicious circle in which the rich get richer, while precarious households go into debt to survive.

A preferential-rate loan hides a trap: buying a car on credit costs much more than its initial price, between capital and interest. This practice, condemned in Islam as Riba, crystallizes financial inequality. Exploring alternative models, such as those proposed by Namlora, offers an ethical way of breaking this cycle. By valuing real assets and interest-free mechanisms, the project embodies an Islamic response to the excesses of the current system.

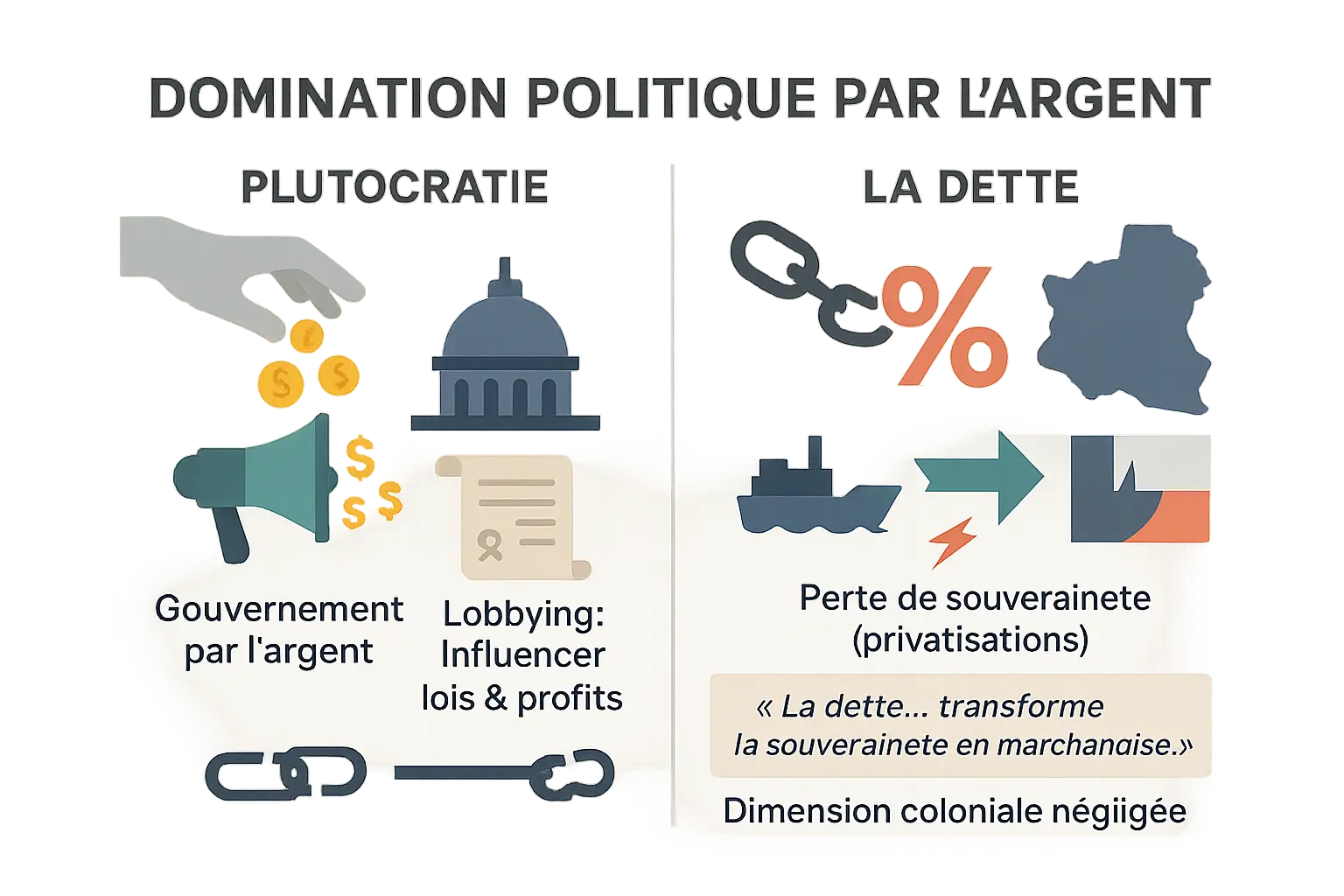

Political domination: when money dictates the laws

Plutocracy: government by the richest

Plutocracy refers to a system in which wealth determines access to power. In Washington, lobbying directly targets elected representatives with colossal budgets, while in Brussels, it relies on technical relationships and expertise. The governments of Donald Trump (USA) and Emmanuel Macron (France), made up of figures from the financial world, illustrate this trend. Noam Chomsky reminds us that modern democracies are often "plutocracies in disguise", where private interests shape public policy.

Debt, a powerful tool of modern colonization

Interest-bearing debt is not just a financial tool; it's a weapon of control that transforms national sovereignty into a commodity negotiable on world markets.

Historically, interest-bearing debt precipitated the fall of empires such as the Ottoman Empire. Today, Burkina Faso devotes 54% of its budget to debt repayment, forcing the privatization of strategic sectors such as energy and water. This logic perpetuates a renewed colonial dimension: creditors impose economic choices on debtors, reinforcing inequalities. According to revues.org, current mechanisms, such as the G20 Common Framework, fail to free indebted countries, keeping them in a cycle of dependency.

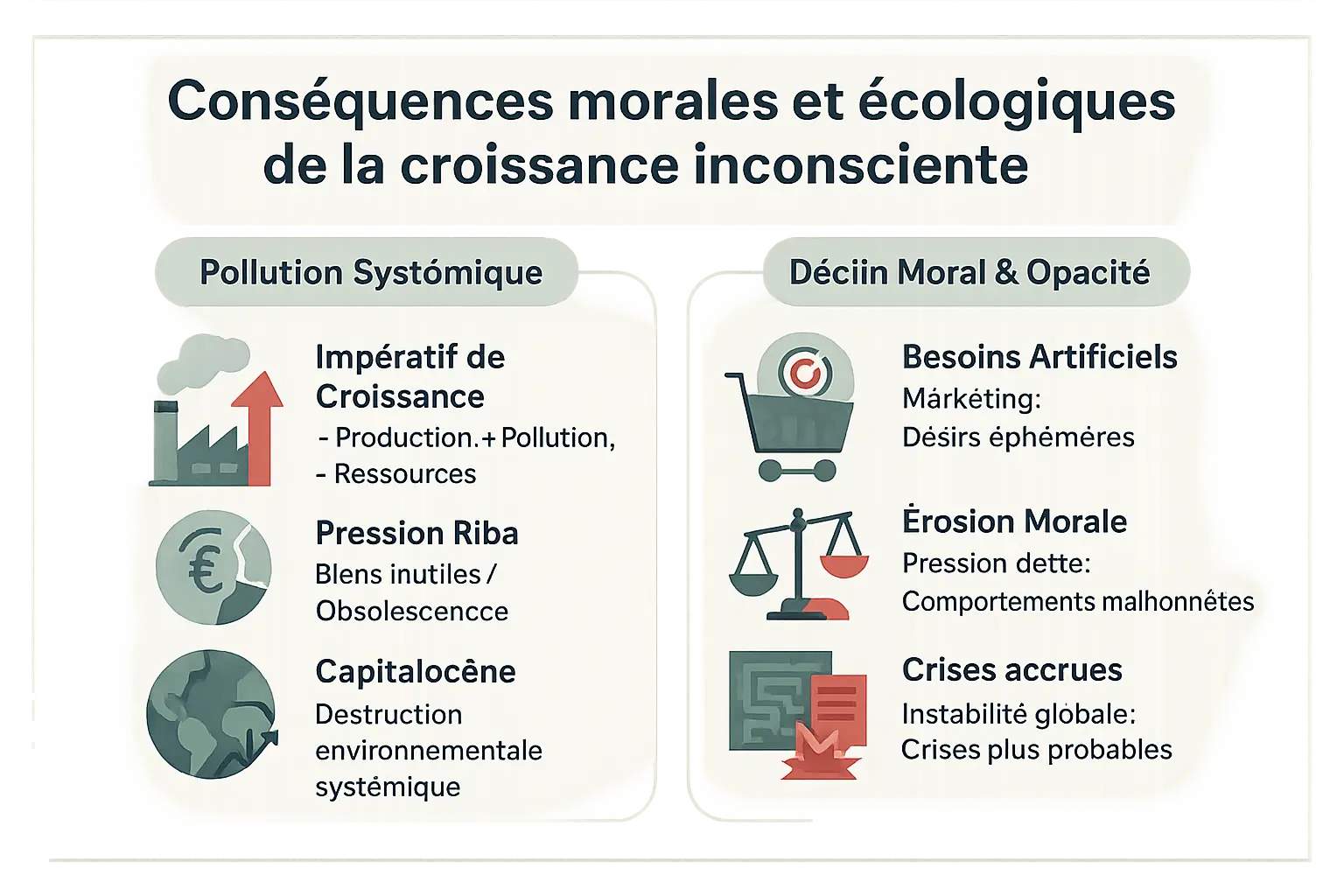

Moral and ecological consequences: growth without conscience

Systemic pollution and the growth imperative

The materialist paradigm inextricably links material growth and environmental degradation. The growth imperative demands constant production, which mechanically generates more pollution and accelerated depletion of natural resources. This logic, underpinned by interest-bearing debt, pushes companies to produce useless or obsolescent goods to cover their financial costs.

The concept of the Capitalocene, explored on OpenEdition Journals, places this ecological destruction within a systemic framework. Unlike the Anthropocene, it attributes the crisis to economic and social relationships, not to humanity as a whole. This critical vision highlights how fossil capitalism structurally destroys natural balances, rooting its extraction in colonial dynamics and historical inequalities.

The loss of values, social ties and opaque complexity

The materialistic system weakens social and moral foundations. To sell more, marketing instrumentalizes ephemeral needs rather than genuine ones, as sociologist Razmig Keucheyan analyzes in his essay on "artificial needs". This dynamic creates a cycle of meaningless consumption, eroding collective values. Individuals, under the pressure of omnipresent debt, risk turning to unethical behavior in order to survive.

Complex financial products exacerbate this breakdown. Three key mechanisms sum up this drift:

- Creating artificial needs: Intrusive advertising and programmed obsolescence generate irrational consumerism, diverting citizens from genuine needs such as solidarity or sustainability.

- Erosion of morality: Financial pressure leads to moral compromises, visible in corporate scandals such as toxic loans or embezzlement.

- System opacity: CDOs (collateralized debt obligations) and CDSs (credit default swaps), structured via complex vehicles (SPV/SPC), mask risks. This dangerous complexity makes crises more likely, as in 2008, and prevents effective regulation.

This financial architecture, born of securitization in the 1970s, has led to major crises. Despite post-crisis regulations (such as the STS standards in Europe), opacity persists. The system, incapable of measuring ecological and social externalities, continues to feed a destructive long-term cycle, to the detriment of future generations and the most vulnerable populations.

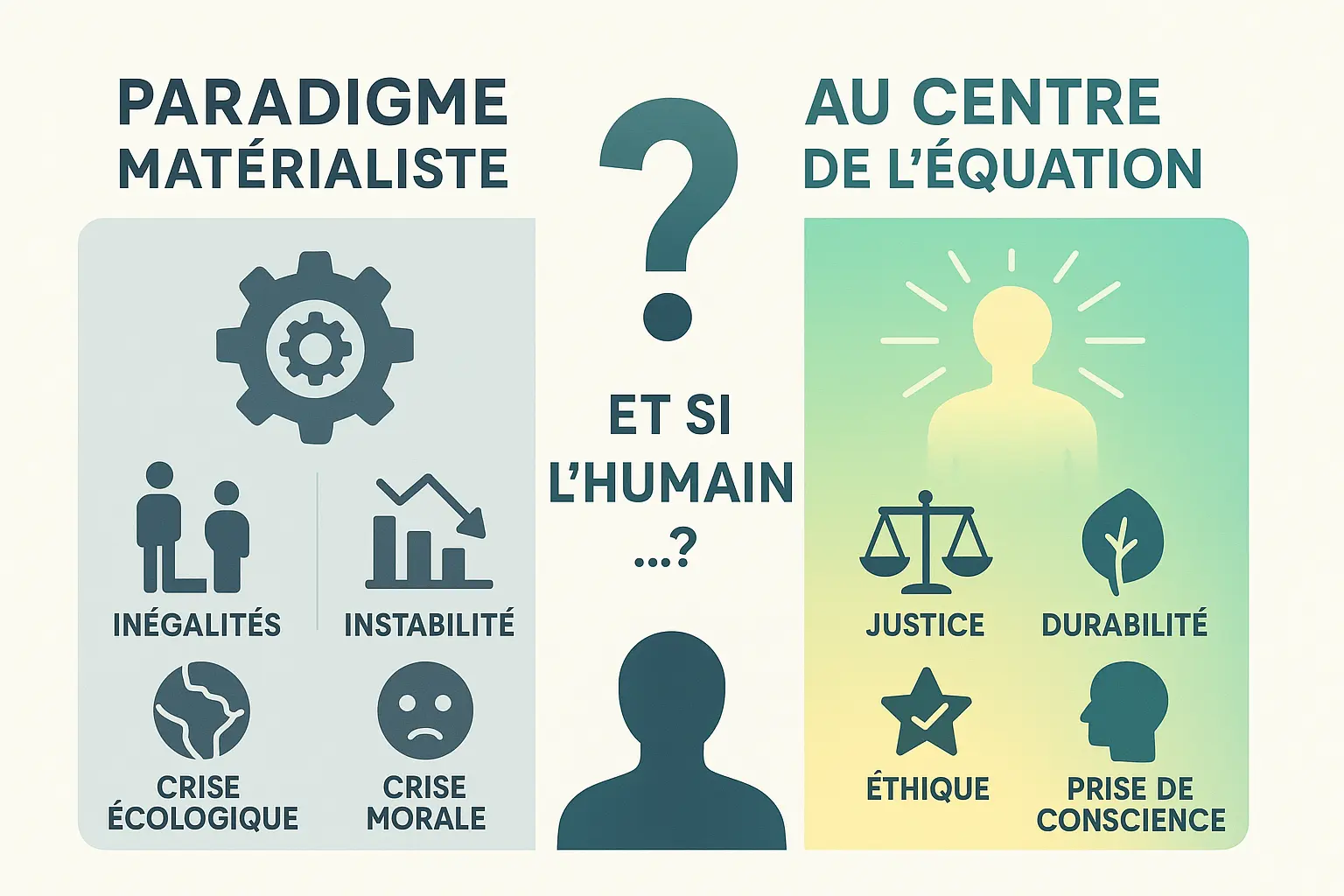

Towards a paradigm shift: what if we restored the human element to its rightful place?

The materialist paradigm, obsessed with growth and the remuneration of capital, has generated historic inequalities, financial instability and a moral and ecological crisis. Today's economic mechanisms, rooted in the logic of immediate profit, have progressively eroded the foundations of social justice and environmental sustainability.

Should we indefinitely accept a model where the human being is reduced to a factor of production, where value is measured by profitability, and where spirituality is relegated to second place? Given these facts, isn't it time to question a system that ignores ethics, justice and humanity?

The alternative lies not in brutal revolution, but in gradual awareness. Understanding the workings of this system is the first step towards a more balanced future. A world where trust, responsibility and sustainability guide economic decisions is not utopian. It simply requires us to rediscover that economics, before being a science of capital, is first and foremost a human science.

The materialistic paradigm, focused on growth and profit, has deepened inequalities, undermined social justice and accelerated the ecological crisis. However, by putting people, ethics and solidarity back at the heart of the system, another economy is imaginable. The first step ? Understand these mechanisms to acting as enlightened citizens.

FAQ

What is the materialistic paradigm governing our global economy?

The materialistic paradigm is like the compass of our global economic system. It points relentlessly towards material growth, profit and production. It is the underlying model of both capitalism and the great economic schools such as Keynesianism and Marxism. To understand it, imagine a gardener who measures the success of his garden only in terms of the number of fruits harvested, totally ignoring the quality of the soil or the well-being of the gardeners. In our economic world, numbers dictate the law, not human or ecological values.

How do you define an economic paradigm, with a concrete example?

A paradigm is like the lens through which we view and interpret the economy. It's our intellectual toolbox for understanding economic systems. Take the materialist paradigm itself: it's our dominant lens, through which we measure the "health" of an economy by its GDP, just as we would measure a person's health solely by their weight rather than their overall well-being. Other paradigms could exist, such as a holistic paradigm that also considers social and ecological well-being.

What is the deeper meaning of economic materialism?

Materialism in economics means placing matter - capital, tangible goods - at the heart of the system. It's like cultivating a garden and worrying only about the harvest, to the detriment of the quality of the soil or the well-being of the gardeners. This paradigm reduces the human being to a unit of production ("labor") and ignores intangible values such as justice, equity or sustainability. It's a bit like measuring the value of a book solely by its price, and not by its content or what it brings to readers.

What is the theory behind this materialist paradigm?

The underlying materialist theory is rooted in the idea that economic value can only be appreciated by what is measurable and quantifiable. It's based on the simple equation: Profit = Success. It's like growing a plant only by its size, ignoring its health or beauty. This model mathematizes the economy in the absence of moral or social values, believing that markets work best when each individual pursues his or her own self-interest, a kind of human "fluid mechanics" where each particle (individual) following its own path would create the overall harmony of the system.

How does this materialistic paradigm manifest itself in our society?

A good example of this can be found in the way we value trades. The materialistic system rewards a trader who trades abstract financial contracts more than a baker who feeds his community. It's as if a village rewarded the man who counted apples more than the man who grew them. Central banks create money through interest, a mechanism that dilutes the value of money in the economy, like a spoonful of syrup in a glass of water. And when debt becomes a tool of power, countries in difficulty hand over their ports or natural resources to repay the debt, in a logic reminiscent of ancient forms of colonization.

What are the fundamental principles of the materialist paradigm?

The principles of this paradigm are simple but powerful: value exclusively the quantifiable (GDP, profit), reduce the human to "labor" and capital to an autonomous entity, and ignore non-measurable values. It's like cultivating a garden with the sole aim of obtaining the largest harvest, with no concern for the quality of the fruit, the fatigue of the gardener or the health of the soil. Interest on capital becomes the driving force, generating money "ex nihilo" (out of nothing) with no counterpart in real value, creating inflation that acts like an invisible tax on the purchasing power of the most vulnerable.

Are there other economic paradigms besides this one?

Three major paradigms stand out in economic history: the materialist one we're describing, the moralist one that would integrate social values, and the ecosystemic one that would take ecological limits into account. The materialist paradigm currently dominates, with its offshoots of neoliberalism, Keynesianism and even Marxism - like different recipes using the same basic ingredients. The other two remain marginal, although the ecological emergency and social crises are driving us to explore them further.

What are some concrete examples of economic paradigms?

The materialistic paradigm can be seen in our obsession with GDP, as if a country's wealth could only be measured in terms of production volume. The moralist paradigm takes shape in Islamic economics, which incorporates ethical considerations. The ecosystemic paradigm would be found in systems measuring "inclusive prosperity" or "ecological footprint". It's like comparing farming methods: conventional (productivist), organic (ethical) and regenerative (holistic).

What does the term "paradigm" really mean?

The word "paradigm" comes from the Greek "paradeigma", meaning " model to follow". In economics, it's like the GPS that guides our decisions, the compass that indicates what counts and what doesn't. The current materialistic paradigm directs us towards material growth. Today's materialistic paradigm directs us towards material growth, as if our economic GPS knew only the direction of profit and ignored all other possible paths. But remember: a paradigm is not an eternal truth, it's just the goal we set ourselves, like choosing to cultivate a garden for its size rather than for its biodiversity.