<meta name="google-site-verification" content="0S72xkYcSqqt100ZuIzn_Zif1zL8vIvcXUmc5Tjo10o" />

Key points to remember: The prohibition of Riba in Islam calls into question systems that generate wealth without effort or risk. By rejecting this mechanism, Islamic finance favors a fair model, based on risk-taking and investment in the real economy, as illustrated by the evolution of Koranic norms in four stages.

Do you feel concerned by these endlessly growing debts, fuelled by invisible interests that are beyond your control? Riba, the logic of effortless enrichment, calls into question the very balance of our financial system, deepening inequalities and weakening economies. Through a legal, ethical and economic analysis, this report explores its Koranic foundations, its current excesses - such as mortgages and student loans - and the concrete solutions offered by Islamic finance. Discover how to break with a cycle of speculation to build a solidarity-based economy, where your money becomes a lever for equity and sustainable growth, in line with your convictions.

Contents

What is Riba and why is it a pillar of ethical finance?

Imagine a financial system where no one profits from the distress of another, where profits are earned through effort and not through the mere passage of time. This is the ambition of Islamic finance, founded on the prohibition of Riba (Arabic رِبًا), a word that literally means "excess" or "increase".

In Islam, Riba encompasses any form of guaranteed profit without effort or risk sharing, be it bank interest, surcharges for late payment or unfair exchanges of identical goods. This practice is categorically haram (forbidden), as recalled in the verses of the Koran (2:275-281) and the Hadiths of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ.

Behind this prohibition lies a radical economic philosophy: money is not a commodity, but a tool of exchange. Unlike conventional systems, Islam demands that wealth be built through work, innovation and risk-sharing. It is this vision that guides organizations such as the International Academy of Islamic Law, which develops ethical standards for modern markets.

This article examines the two major forms of Riba: Riba al-Nasi'ah (interest on loans) and Riba al-Fadl (imbalance in the exchange of identical goods). We will analyze their consequences - concentration of wealth, economic instability - and explore concrete alternatives: Musharaka (partnership), Murabaha (sale with known margin) or Ijarah (leasing), all solutions promoting justice and economic resilience.

A study byAAOIFI (Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions) reveals that countries adopting these principles experience 30% fewer financial crises. Far from being anachronistic, these precepts offer pertinent responses to modern systemic instability.

Doctrinal foundations: where does the prohibition of Riba come from?

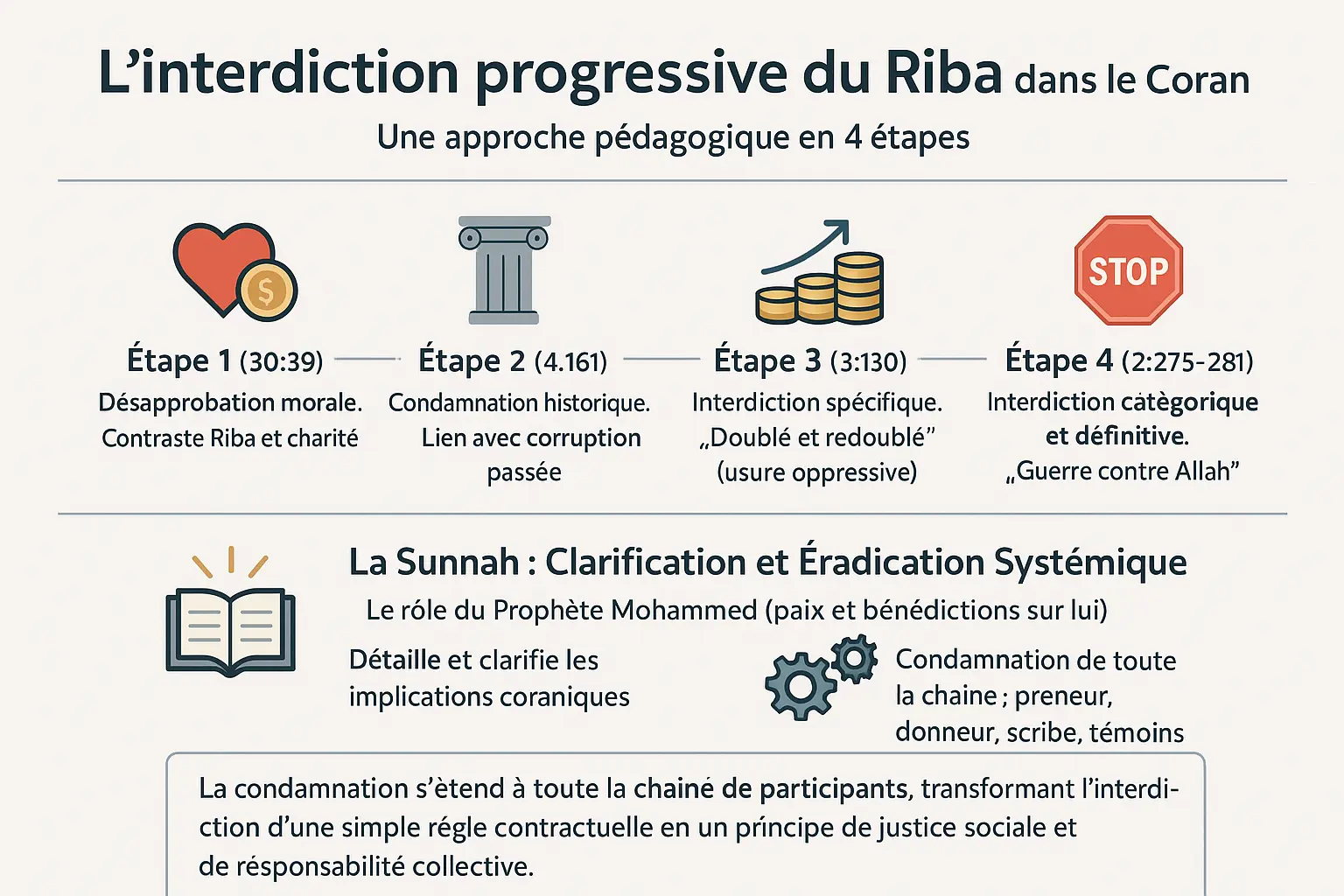

Progressive prohibition in the Koran: a pedagogical approach

Riba, the Arabic word for "usury", is central to Islamic finance. The prohibition was gradually affirmed in the Koran, adapted to the society of the time.

Sura ar-Rûm, verse 39, condemns usury in contrast to Zakaat: "What you give in usury... does not increase with Allah". This ethic of sharing takes precedence over accumulation.

Sura an-Nisâ', verse 4:161, links Riba to the corruption of past communities, such as the Jews, illustrating its spiritual and economic impact.

Sura Âli 'Imrân, verse 130, forbids Riba al-Jahiliya, where debts were multiplied in the event of delay. This pre-Islamic practice trapped debtors in destructive cycles.

Sura al-Baqara, verses 275-281, describes Riba as "war against Allah and His Messenger", a unique condemnation underscoring its seriousness.

The condemnation extends to all players, transforming Riba into an issue of social justice.

The Sunnah: clarification and condemnation of the entire ecosystem

The Sunnah specifies and reinforces the Koranic prohibition. It encompasses all actors: a Hadith reported by Jabir Ibn 'Abdillah curses the lender, the debtor, the scribe and the witnesses.

A Hadith by Abu Huraira emphasizes: "One dirham of Riba is more serious than thirty-six fornications". This comparison underlines the priority given to eradicating Riba.

Riba is a systemic corruption, not an isolated sin. The Sunnah establishes an ethical financial system, consistent with Namlora's values.

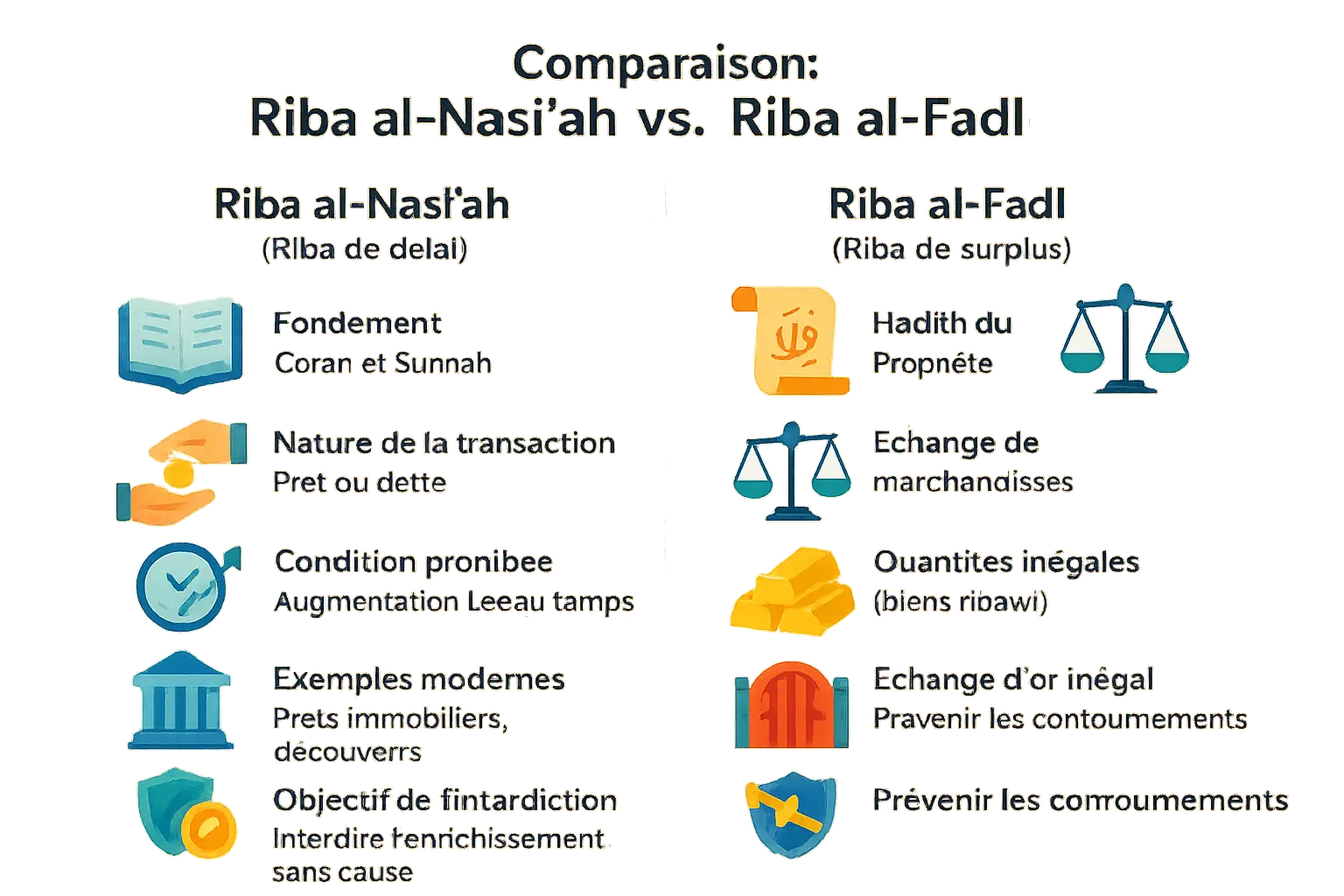

The two faces of Riba: Riba al-Nasi'ah and Riba al-Fadl

Islamic finance distinguishes two main forms of Riba, prohibited by the Shari'a to protect economic equity. These two faces, Riba al-Nasi'ah (delay interest) and Riba al-Fadl (surplus in exchange), govern both modern loans and ancient commercial transactions.

Riba al-Nasi'ah: time-related interest

Riba al-Nasi'ah refers to any surplus demanded on a loan in exchange for a deferred payment. This includes traditional bank loans (real estate, student loans), interest-bearing savings accounts, and even government bonds. The International Academy of Islamic Fiqh (Majma' al Fiqh al Islami) has clearly ruled that even moderate interest falls into this category.

Imagine a farmer borrowing €10,000 to buy seeds, with an obligation to repay €11,000 after harvest. This difference of €1,000, guaranteed by the simple passage of time, constitutes Riba al-Nasi'ah. This mechanism transforms money into an autonomous commodity, detached from real economic activity.

Riba al-Fadl: the surplus in the exchange of goods

Riba al-Fadl prohibits the exchange of unequal quantities of goods of the same kind, known as ribawi. For example, exchanging 100g of pure gold for 110g of the same gold is prohibited, even if it's an immediate exchange. This rule applies to six categories of goods: gold, silver, wheat, barley, dates and salt.

This prohibition acts as a safeguard. It prevents attempts to circumvent Riba al-Nasi'ah through double transactions. Take an investor wishing to buy gold with an interest-bearing loan. He could theoretically resell the gold immediately at a higher price, transforming a loan into a commercial exchange. Riba al-Fadl blocks this circuitous route.

| Features | Riba al-Nasi'ah (Delay Riba) | |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Koran and Sunnah | Hadith of the Prophet |

| Nature of transaction | Loan or debt | Exchange of goods |

| Prohibited condition | Increase due to the passage of time | Inequality of quantities for the same ribawi good |

| Modern examples | Interest on a mortgage, bank overdraft | Exchange of gold of different qualities in unequal quantities |

| Purpose of the ban | Prohibiting time-based unjust enrichment | Preventing bypasses and closing the door to disguised Riba |

The logic of blocking the gates (Sadd al-Dhara'i) justifies this second form. Just as a farmer erects dykes to prevent flooding, Islamic finance erects legal barriers to prevent usurious practices. This precaution applies even in surprising cases: the Prophet forbade accepting a gift from a debtor, lest it become a pretext for concealing interest.

For those wishing to invest in gold in a halal way, this rule makes perfect sense. A gold exchange must respectequality of quantity and quality, guaranteeing a fair transaction. This discipline reminds us that wealth, like water, must circulate freely without creating speculative bubbles.

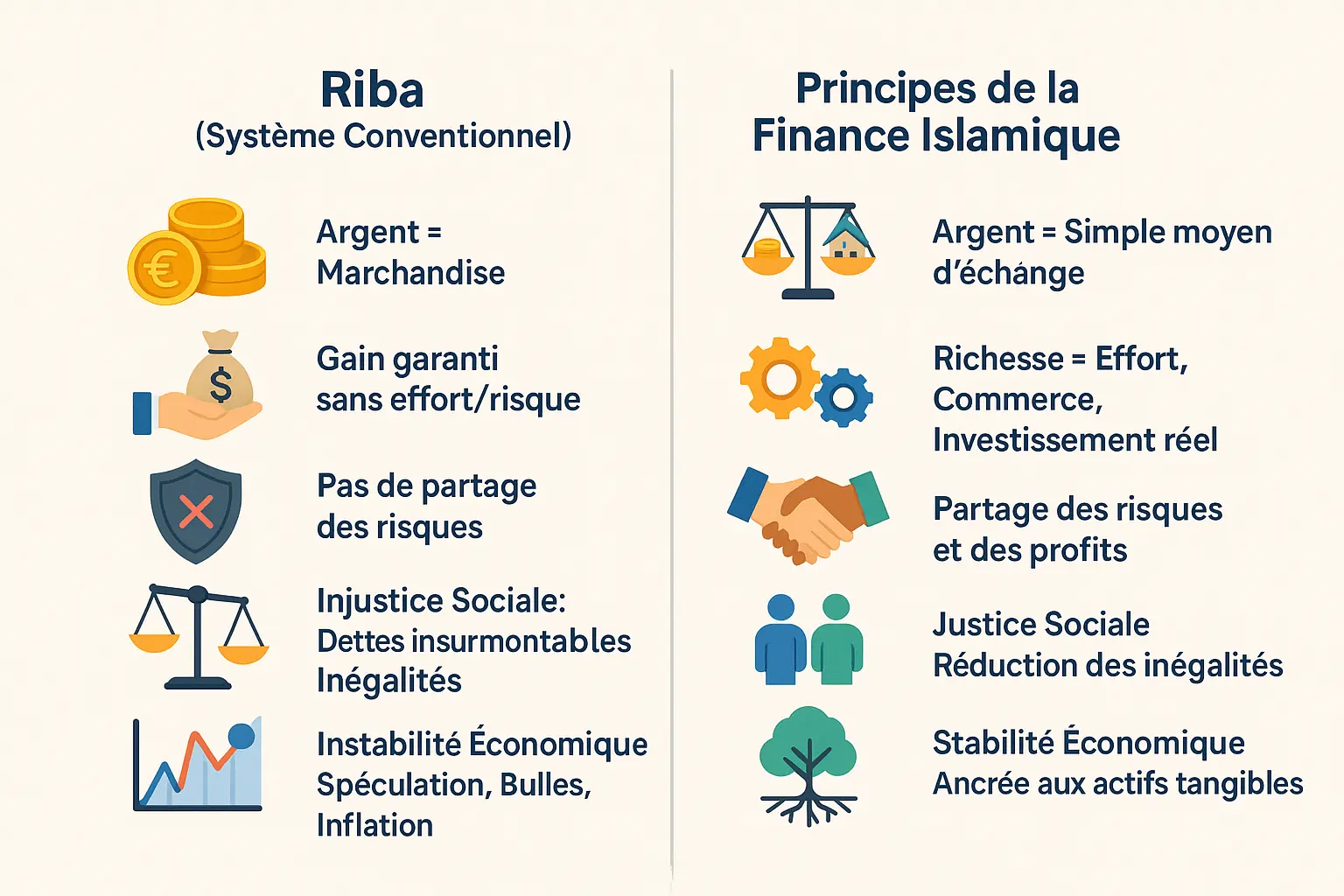

The wisdom behind the ban: social justice and economic stability

Money as a medium of exchange, not a commodity

In Islam, money has no intrinsic value. It is simply a means of exchange and a unit of measurement of value, not a commodity that generates value. Legitimate wealth comes from effort, trade or investment in the real economy, as a good produced or a service rendered. This ethical vision is opposed to the modern idea of money generating money via Riba. Islamic finance, embodied by platforms such as Namlora, puts money back at the heart of the real economy, by linking it to tangible assets (real estate, agricultural projects, SMEs) to avoid speculative excesses.

Riba violates this fundamental principle. A lender obtains a guaranteed gain without effort or risk-taking, dissociating money from the creation of value. Islam encourages the transformation of capital into an investment partner, sharing risks and profits. Contracts such as the Mudaraba (a partnership in which capital is provided by an investor and managed by an entrepreneur) or the Musharaka (a full partnership in which capital and skills are provided) embody this logic. Namlora facilitates these models, linking savers to productive projects while guaranteeing transparency and compliance with Sharia law.

A bulwark against injustice and instability

Riba widens social inequalities. Lenders profit from the distress of others, trapping borrowers in cycles of insurmountable debt. Investopedia points out that this dynamic widens the gap between rich and poor, particularly in developing economies where public debt absorbs social budgets. In some countries, for example, interest on government loans exceeds spending on health and education, exacerbating precariousness.

But Riba also fuels macroeconomic instability. Debt and interest in the conventional system generate inflation, an "invisible tax" affecting the most vulnerable. This systemic inflation weakens the economy. Islamic finance, anchored in tangible assets, limits speculation. The AAOIFI and the Majma' al Fiqh al Islami have clearly ruled that bank interest, whether on property loans or bonds, constitutes a form of Riba al-Nasi'ah. These institutions remind us that money must serve the real economy, not speculate in it.

In rejecting Riba, Islam has developed concrete mechanisms such as Mudaraba (profit partnership) and Musharaka (full partnership). These models value transparency and justice, reinforcing trust and collective responsibility. In contrast to interest-based systems, they avoid speculative behavior while relying on real assets for economic stability. Namlora embodies this vision by connecting investors, entrepreneurs and consumers around halal projects, placing spirituality and justice at the heart of financial exchanges.

How can you live without Riba in a conventional world?

The challenge of indirect Riba and purification of income (Tazkiyah)

Being Muslim and living in a global financial system dominated by Riba is a daily challenge. Even with the best will in the world, you can be exposed to illicit income without meaning to. For example, interest generated by an ordinary bank account, or even dividends from companies whose finances include prohibited products.

In response to this reality, Islamic jurisprudence has developed a practical solution: Tazkiyah, or purification of illicit income. This process does not involve "redeeming" a sin by giving alms, but rather freeing oneself from an ethical burden by renouncing illicit profit.

- Donated to charity: money purified in this way must be given in its entirety to legitimate beneficiaries (the poor, orphans, foreigners in difficulty) with no hope of return.

- Can't benefit from it: Neither you nor those around you can use this money for personal, religious or community projects.

- Act of repentance: This gesture is not a Sadaqah deserving divine reward, but a voluntary abandonment of illicit gain.

Imagine a gardener removing weeds to preserve his crops. Tazkiyah works the same way: it cleans your capital to maintain the integrity of your investors and projects.

The role of the guardians of ethics: AAOIFI and Majma' al Fiqh

The transition from religious theory to financial practice requires safeguards. Two major institutions ensure this mediation: the AAOIFI (Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions) and the Majma' al Fiqh al Islami (International Academy of Islamic Law).

AAOIFI has established concrete criteria for assessing investment compliance. For example:

- Riba-based debt must not exceed 30% of a company's market capitalization.

- Revenues from non-compliant activities (such as interest) must remain below 5% of total sales.

These thresholds transform abstract principles into operational tools. These standards are essential for halal stock market investingby minimizing exposure to Riba while opening up economic opportunities.

The Majma' al Fiqh al Islami completes this framework by issuing legal opinions on borderline cases, such as the interpretation of modern contracts through the prism of Shari'ah. Together, these institutions form a shield against abuses, while enabling the evolution of Islamic finance.

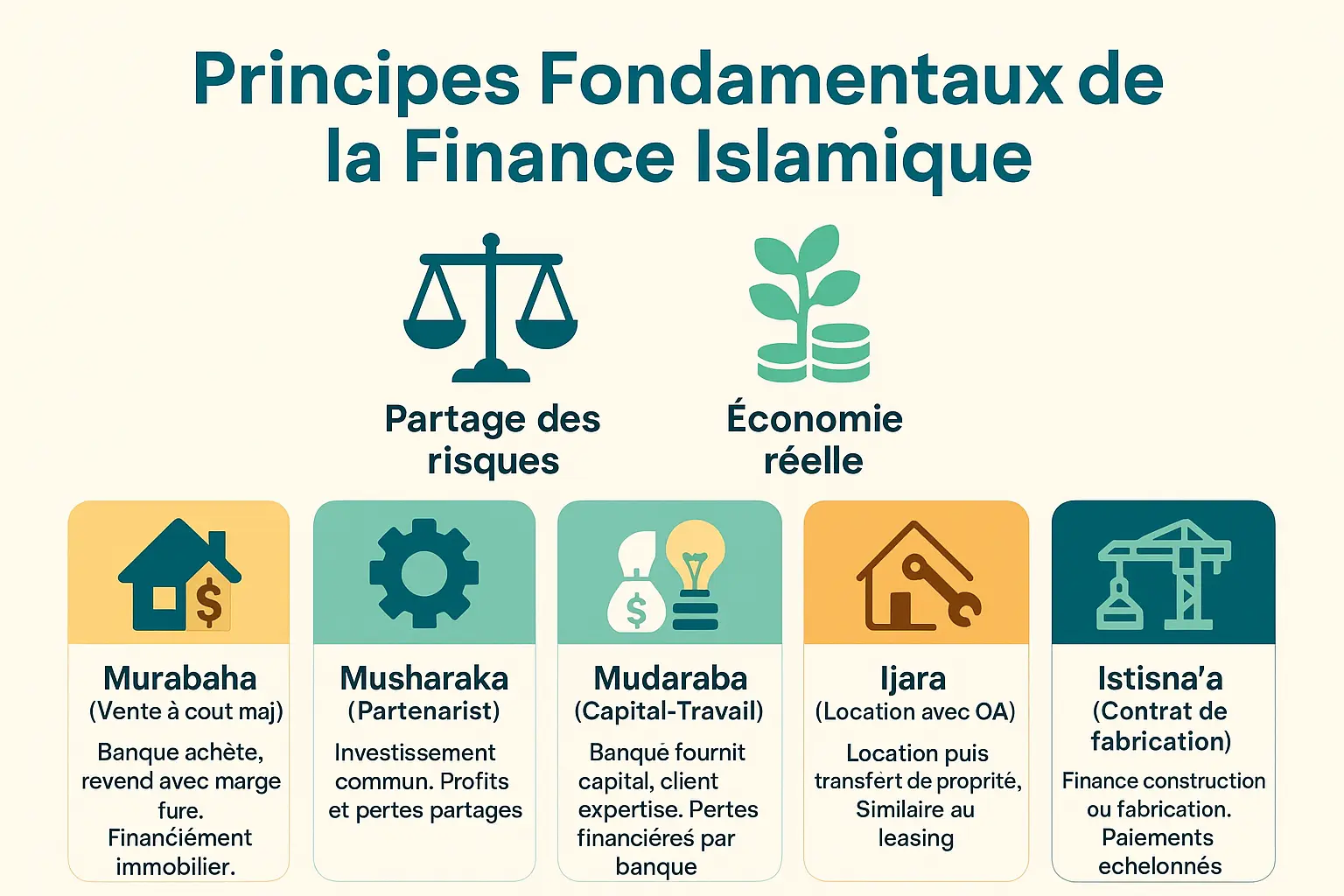

Practical alternatives to Riba: the pillars of Islamic finance

Islamic finance is not just a list of prohibitions. It proposes a constructive system rooted in the real economy and based on risk-sharing. Unlike traditional systems, where lenders receive guaranteed income without effort, these tools oblige all players to commit to productive projects. It's an ethical revolution where wealth is created through collaboration and mutual risk-taking.

The main contracts in Islamic finance

- Murabaha (cost-plus sale): The bank buys an asset (such as a house) and resells it at a higher price. It's a sale, not a loan. This is the most common mechanism for halal real estate financing, with installments spread over 25 to 30 years.

- Musharaka (partnership): An alliance in which the bank and the entrepreneur invest together. Profits and losses are divided according to ratios set at the outset. For example, in a real estate partnership, the bank and the investor share the rental income according to their contribution.

- Mudaraba (capital-labour partnership): The bank provides 100% of the funds, and the entrepreneur manages the project. Profits are shared, but losses fall entirely on the bank. This is a lever for Islamic funds supporting startups, with losses borne by the investors.

- Ijara (lease with purchase option): The bank buys an asset and leases it to the customer. At the end of the contract, ownership is transferred. This is an alternative to traditional leasing, used for professional equipment or housing. A company leases agricultural machinery, avoiding interest-bearing loans.

- Istisna'a (manufacturing contract): The bank finances the construction of a property by making progress payments. Ideal for tailor-made projects, the financing follows the progress of the work. A developer obtains funds spread over the various stages of construction, limiting speculation.

Despite their potential, these tools remain under-exploited. According to Dr. Mohamed Talal Lahlou, Islamic banks focus mainly on Murabaha, accounting for 79% of financing. Yet mechanisms such as Musharaka and Istisna'a could transform access to credit for SMEs. For example, Sukuk for infrastructure or Salam contracts for agriculture would reinforce economic justice. Diversifying supply is an ethical and strategic imperative, aligning Islamic finance with its foundations: equity, stability and shared responsibility.

Towards a more ethical and resilient economy

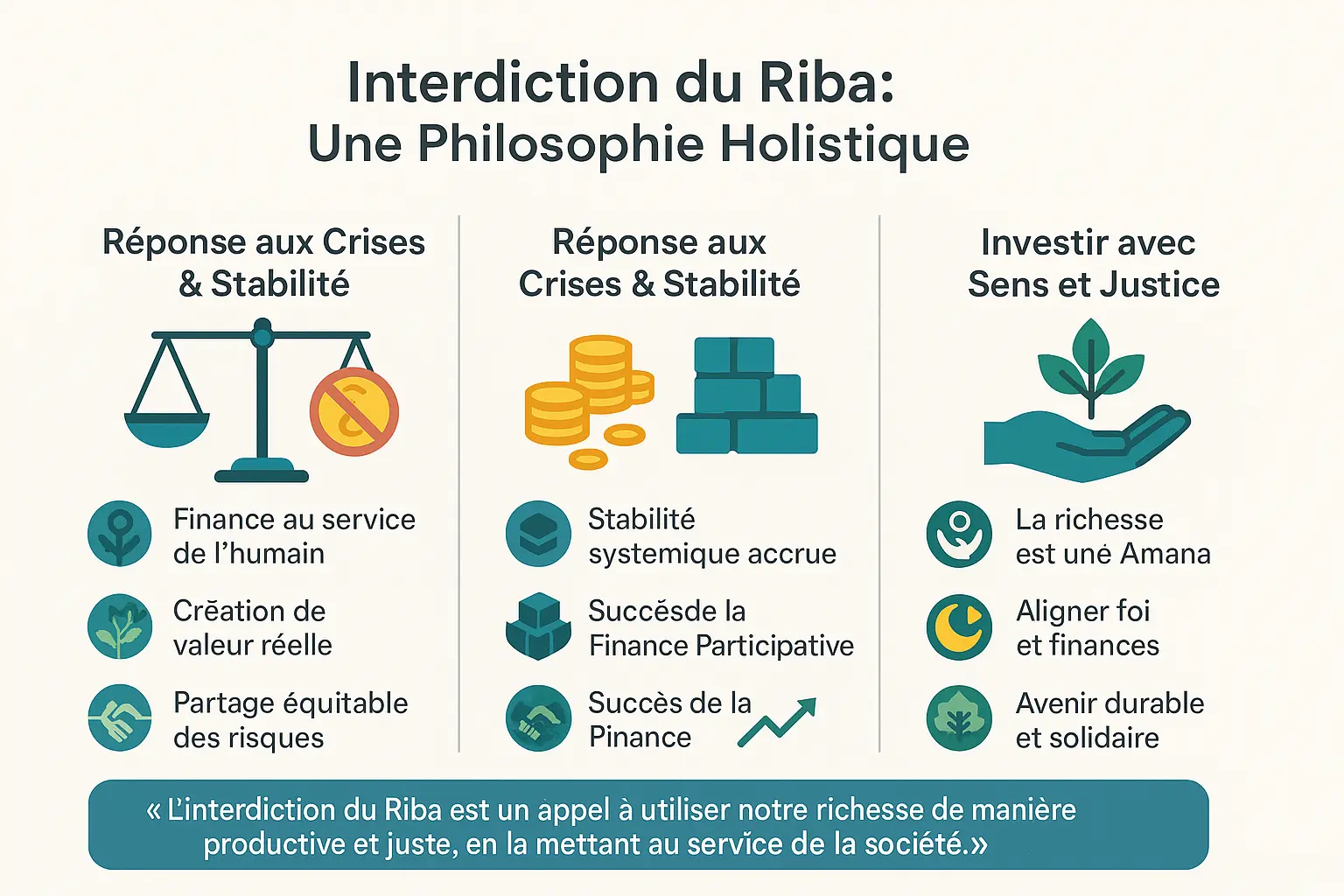

In Islam, the prohibition of Riba embodies a holistic economic philosophy, challenging conventional finance. It is not a taboo, but a doctrine aimed at generating wealth through effort, risk-sharing and real assets. Money is a tool of exchange, not a commodity.

In the face of today's crises, participatory finance offers a balanced alternative. Despite mixed results on its resilience to Covid-19, its principles - profit/loss sharing, financing of tangible assets - limit speculation. Contracts such as Mudaraba and Musharaka are concrete examples of this, although its potential for SMEs and financial inclusion remains to be explored.

Ultimately, the prohibition of Riba is a call to use our wealth productively and justly, putting it at the service of society.

Wealth is an Amana - a sacred responsibility. Investing without Riba puts this idea into practice by aligning spiritual and social values. Supported byAAOIFI and Majma' al Fiqh, Islamic finance embodies a vision where trust, justice and sustainability guide financial choices. A model that redefines the relationship with money, seeing it as a means, not an end, to building a collective future.

The prohibition of Riba embodies a an ethical vision where finance serves people. With participative finance, your choices become levers for social justice.

Transforming our wealth into a productive and fair force means investing in a future aligned with your values.

Your money, a responsible ally, shapes a sustainable economy.

FAQ

What is Riba in Islam?

Riba, an Arabic word meaning "excess" or "surplus", is a central concept in Islamic finance. In Islam, it is categorically forbidden(haram) because it represents gain without effort or risk-taking. Imagine a gardener demanding fruit from a tree without having sown the seed or watered the roots: this is the idea behind the prohibition of Riba. This principle is part of a broader vision of an ethical economy, where wealth is built through hard work, innovation and risk-sharing.

The scriptural roots of this prohibition go back to the Koran and the Sunnah. It progressively asserted itself through four stages of revelation, culminating in an unambiguous condemnation. This pedagogical approach aimed to transform practices rooted in pre-Islamic society, demonstrating the depth and relevance of the principle.

What is Riba credit?

Riba credit refers to any interest-bearing loan, be it a mortgage, consumer credit or even an interest-bearing savings account. In Islam, this system is considered a "war against Allah and His Messenger" (Qur'an 2:275), as it allows the lender to earn effortlessly, while exposing the borrower to disproportionate risks.

The Sunnah goes further, cursing not only the lender and borrower, but also the scribe and witnesses to the transaction. This systemic condemnation transforms the prohibition of a simple contractual rule into a principle of social justice. It's as if society as a whole refused to endorse a system where money begets money, without creating real value.

What types of Riba are there?

Two main forms of Riba are recognized in Islamic jurisprudence:

Riba al-Nasi'ah (time-related interest): This is the most common type, corresponding to any increase in a debt linked to deferred payment. A home loan, a bank overdraft, or even interest on a savings account are modern examples.

Riba al-Fadl (surplus in exchange): Less obvious to our modern economy, this concerns the unequal exchange of goods of the same kind, such as exchanging 100g of pure gold for 110g of pure gold. This rule prevents subterfuge that could circumvent the prohibition of Riba al-Nasi'ah.

These two forms aim to preserve the integrity of the Islamic financial system, by prohibiting not only the illicit act, but also the mechanisms that could lead to it.

Why is interest haram?

The prohibition of Riba goes far beyond a simple religious rule. It is based on a profound vision of money as a "medium of exchange", not as a "commodity". In Islam, money should not generate wealth on its own, but be a tool to enhance the real economy through effort and shared risk-taking.

Economically, the Riba system creates inequalities by concentrating wealth in the hands of lenders, trapping borrowers in cycles of debt. It also encourages financial instability through speculative money creation. Islamic finance proposes an alternative model based on risk-sharing (Mudaraba, Musharaka), aligning the interests of all economic players.

How can I save without riba?

nvesting without Riba is not only possible, but also ethically rewarding. Islamic finance offers concrete solutions:

Murabaha: The bank buys an asset and sells it back to you with a profit margin, as in real estate financing.

Mudaraba: You provide the capital, a partner provides the expertise, and profits are shared according to a predefined ratio.

Musharaka: A complete partnership where capital and labor are shared, with profits and losses shared equally.

Tools such as Ijara (hire-purchase) or Istisna'a (manufacturing contract) also offer innovative alternatives. More than a simple ban, this system encourages a productive economy rooted in reality.

What is the punishment for riba in Islam?

The seriousness of Riba is underlined in scriptural sources. The Qur'an calls it "war against Allah and His Messenger" (Qur'an 2:275), and an authentic Hadith curses not only the one who takes and gives Riba, but also the scribe and witnesses. This systemic condemnation shows that Riba is not an isolated individual fault, but a corruption that affects the entire value chain.

On a spiritual level, Riba is considered a major sin requiring sincere repentance and purification of one's wealth (Tazkiyah). This act consists in giving illicit income to charity, without deriving any personal benefit. It is a process of moral and financial purification, anchoring individual and collective responsibility.

How can I get rid of my Riba money?

The purification of money from Riba(Tazkiyah) is a clearly defined process in Islamic finance. When you receive unlawful income (such as bank interest), the solution is to donate it to charity. This money, illicit for you, becomes licit for the beneficiaries, such as the poor or destitute.

Several rules govern this purification: the money cannot be used for religious projects (building mosques, buying holy books), nor can it be kept by the person who earned it. It's an act of repentance, not a spiritually rewarding almsgiving. This approach illustrates the rigor and benevolence of Islamic finance, which offers practical solutions in a world dominated by the conventional system.

How to buy Riba-free in France

In France, a number of Islamic banks and banking services offer Shari'ah-compliant solutions for property purchases. Murabaha is the most widespread solution for real estate financing: the bank buys the property and sells it back to you with a profit margin, without charging interest.

Institutions such as Al Amana or specialized departments within conventional banks (such as Crédit Agricole or BNP Paribas) offer these solutions. For professional purchases, Musharaka (partnership) or Ijara (hire-purchase) are viable alternatives. Although less accessible than traditional products, these tools offer responsible finance in line with Islamic values and contemporary economic realities.

How do I get out of Riba?

Getting out of Riba is a gradual process, but perfectly feasible thanks to Islamic finance. Start by closing your interest-bearing accounts and transferring your savings to Islamic current accounts. For investments, opt for funds screened according to AAOIFI criteria, which limit debt to 30% of capitalization and non-conforming income to 5% of sales.

For major purchases, opt for Murabaha (Islamic credit sale) or Ijara (hire-purchase). For professional projects, Musharaka (partnership) or Mudaraba (capital-work partnership) offer stable frameworks. Finally, regularly purify your finances(Tazkiyah) to get rid of the illicit income inevitable in a conventional system. This path, while requiring adaptation, leads to a fairer, more sustainable form of finance.