<meta name="google-site-verification" content="0S72xkYcSqqt100ZuIzn_Zif1zL8vIvcXUmc5Tjo10o" />

The key point to remember: The prohibition of Riba, equivalent to modern interest according to AAOIFI and Majma', embodies values of justice. Musharaka and Murabaha replace loans, anchoring financing in the real economy. Ensuring greater stability and avoiding speculative bubbles, this system restores confidence to 9% of Muslims through compliant practices.

Le riba intérêt cachent-ils des réalités économiques aussi divergentes que leurs racines éthiques ? Explorez l’analyse juridique et financière des positions de l’AAOIFI et du Majma‘ al-Fiqh al-Islami, unanimes à condamner l’exploitation monétaire au profit d’une économie réelle et solidaire. Découvrez comment des solutions islamiques, comme la Murabaha ou la Musharaka, transforment le risque en opportunité, tout en respectant les fondements de la Shari’ah. Derrière ces mécanismes, c’est un idéal de justice sociale et de partage des profits qui s’incarne, défiant les logiques de spéculation et d’injustice héritées d’un système financier conventionnel. Une finance où l’éthique et l’équité guident chaque transaction.

Contents

Riba and interest: the foundations of a crucial distinction

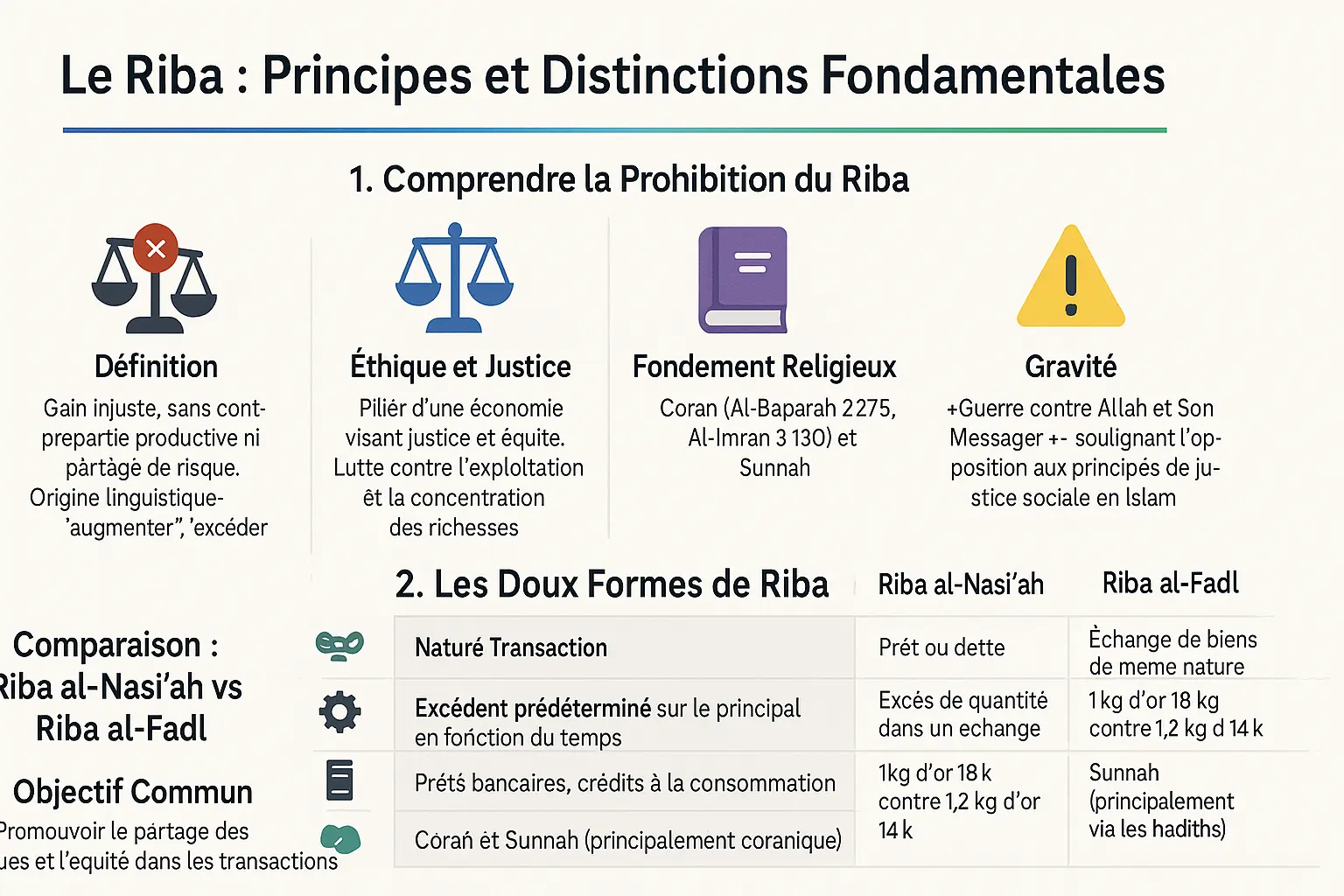

Riba prohibition: a question of ethics above all

Riba derives from the Arabic root "raba", meaning "to increase" or "to exceed". Although often translated as "usury" or "interest", the term refers to any unjust gain without real consideration or risk-sharing. This central concept in Islamic finance aims to establish justice and fairness in economic exchanges.

The Koran strongly condemns Riba. In Sura Al-Baqarah (2:275), it compares those who collect Riba to "those whom the Devil has struck mad", underlining the irrationality of a system where money generates money without effort. Sura Al-Imran (3:130) explicitly forbids "split Riba", combating the excessive accumulation of wealth.

"Those who do not abandon Riba are at 'war with Allah and His Messenger', a statement that underlines the seriousness of this practice and its opposition to the principles of social justice in Islam."

These sacred texts form the moral basis of the Islamic economy, where prosperity is based on productive exchange. To find out more, check out this financial source explaining why Riba is perceived as unjust gain.

Riba al-nasi'ah and Riba al-fadl: the two faces of prohibited interest

Classical jurisprudence distinguishes between two forms of Riba:

Riba al-nasi'ah (delay) concerns interest on debt. It is a time-related surplus on a loan or a deferred sale. Example: a loan of €10,000 repaid for €11,000, the extra amount representing Riba. This type of practice was common in pre-Islamic times, and is directly targeted by the most severe Koranic verses.

Riba al-fadl (excess) governs the unequal exchange of "ribawi" goods: gold, silver, wheat, barley, dates and salt. This preventive prohibition prevents misappropriation of Riba al-nasi'ah. For example, exchanging 1kg of pure gold for 1.2kg of impure gold, even immediately, constitutes Riba al-fadl.

| Features | Riba al-Nasi'ah | Riba al-Fadl |

|---|---|---|

| Type of transaction | Loan or debt | Exchange of goods of the same kind |

| Mechanism | Surplus on principal as a function of time | Excess in an immediate exchange |

| Examples | Bank loans | Exchange 1kg of gold for 1.2kg of gold |

| Foundation | Koran and Sunnah | Sunnah (hadiths) |

These two forms of Riba aim to promote fair transactions, in line with Islamic principles of equity. They illustrate how Islamic finance establishes a system where value comes from real production, not from monetary benefits.

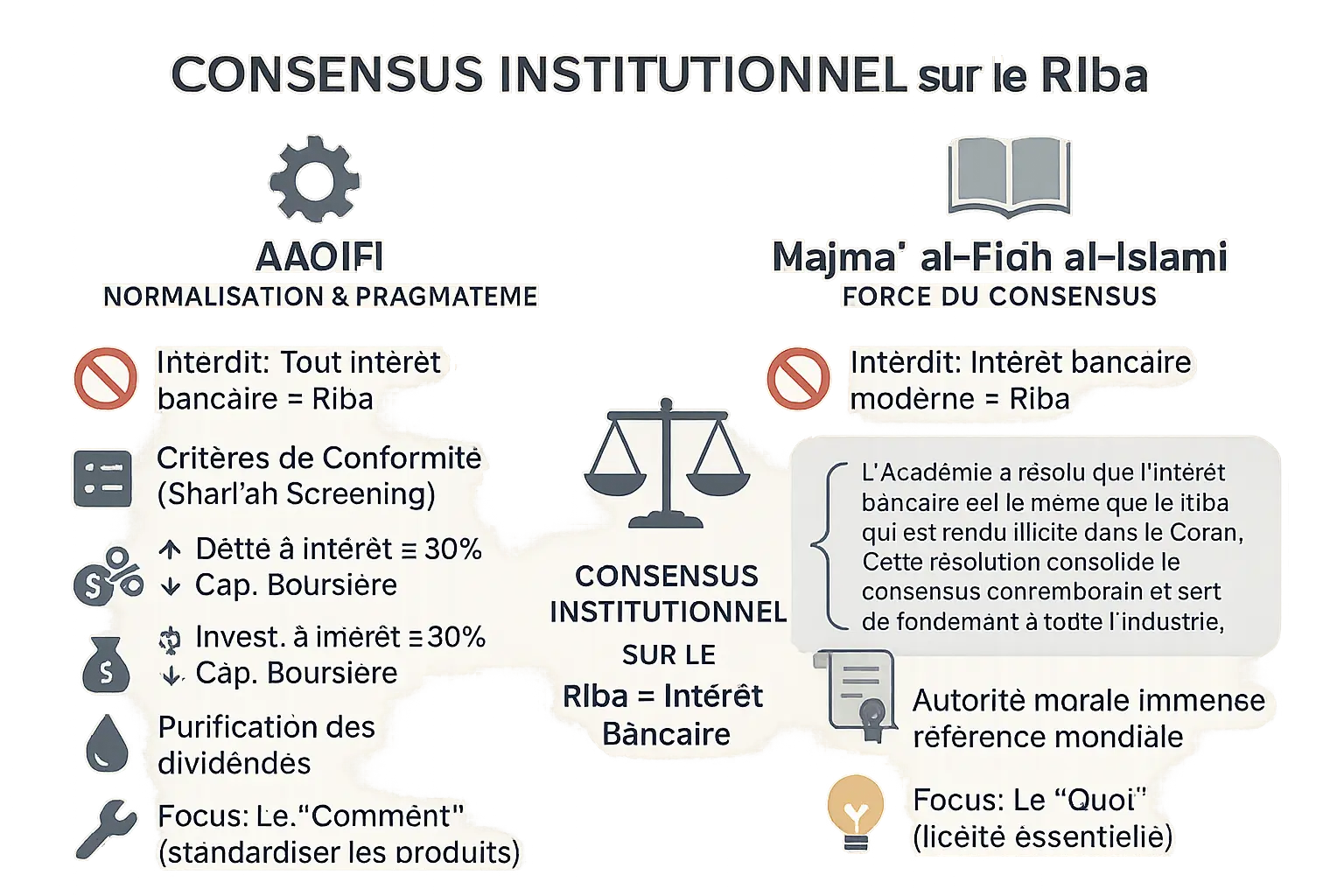

AAOIFI and Majma' al-Fiqh al-Islami: the institutional consensus on riba

The prohibition of Riba in Islamic finance rests on two pillars: the AAOIFI (Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions) and the Majma' al-Fiqh al-Islami. Although their methodologies differ, they converge on one key point: modern bank interest is a form of Riba prohibited by the Koran. Their collaboration structures operational standards while anchoring them in Islamic jurisprudence.

AAOIFI: between rigorous standardization and market pragmatism

The AAOIFI, created in 1991, defines the technical standards of Islamic finance, applied in countries such as Bahrain and Pakistan. For it, all bank interest (simple, compound, modest or high) constitutes Riba al-nasi'ah and is forbidden.

Its Shari'ah screening criteria for investments in non-Islamic companies reflect a pragmatic approach:

- Interest-bearing debt ≤ 30% of market capitalization

- Interest-bearing assets ≤ 30% of capitalization

- Non-compliant revenues capped at 5% of total revenues

Investors must purify dividends by eliminating non-compliant shares through charitable donations. This practice embodies the balance between theological ideals and economic realities.

Majma' al-Fiqh al-Islami: the power of scholarly consensus

The Majma' al-Fiqh al-Islami, the legal body of the OIC, brings together scholars from all Islamic schools. Its opinions (fatwas) form the modern consensus (Ijma'). Its major resolution declares bank interest to be equivalent to Qur'anic Riba.

"The Academy has resolved that bank interest is the same as Riba forbidden in the Koran. This resolution serves as the foundation for the entire industry."

While the AAOIFI formalizes technical standards, the Majma' establishes legal principles. This complementarity ensures dual legitimacy: doctrinal for the Majma', operational for the AAOIFI. Their tandem has made it possible to structure products such as Murabaha and Musharaka, despite criticism of the quantitative thresholds and the substance of the mechanisms.

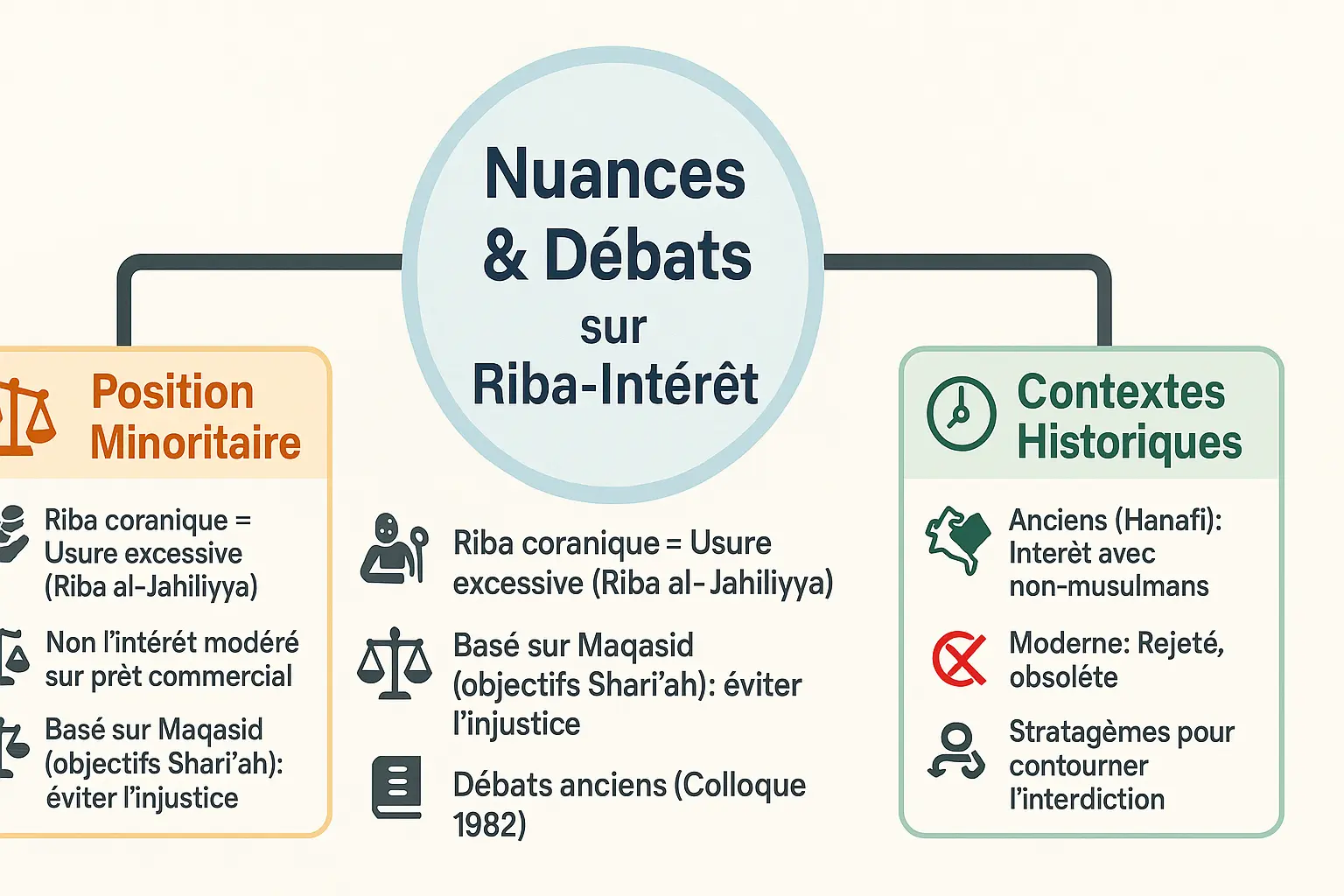

Beyond consensus: debates and nuances on the fairness of Riba and interest

Une équivalence Riba Intérêt réellement unanime ?

The majority position of Islamic institutions regards modern bank interest as a form of Riba al-nasi'ah, the pre-established surplus in a loan. However, a minority position emerging notably in the work of Mohammad Omar Farooq challenges this strict equivalence.

These minority voices rely on a reading that focuses on the objectives of the Shari'ah (maqasid). According to this interpretation, the prohibition is specifically aimed at Riba al-Jahiliyya, the pre-Islamic usurious practice of doubling the debt of a debtor in difficulty. A moderate interest rate on a commercial loan between solvent parties would not fall under this prohibition, as it would respect economic equity.

This debate dates back to a symposium held in 1982, illustrating the tension between a literal reading of sacred texts and a functional approach to ethical goals. For its advocates, this vision makes it possible toadapt Islamic finance to today's economic realitieswithout betraying its essence.

Historical interpretations: the case of Dar al-Harb and the "hilah".

The Hanafi school played a key role in developing a historical exception for transactions in Dar al-Harb (war territory). The jurists Abu Hanifa and Muhammad once authorized Riba between Muslims and non-Muslims in these contexts, based on a hadith reported by Mak'hool.

This position, now widely rejected, was based on the idea that enemies' property could be legitimately acquired in times of conflict. The application of this principle to the modern economy remains problematic, with contemporary scholars emphasizing the obsolescence of the Dar al-Harb concept in a globalized world.

The notion of legal tricks (hilah) also emerges from historical debates. Some Hanafi jurists accepted arrangements such as "double selling" to circumvent the prohibition of Riba. As this research article shows, these practices illustrate the challenges of applying Islamic principles in complex economic contexts.

Today, these historical exceptions serve above all as a transition to modern critiques of "hilah" such as organized Tawarruq, Islamic financial models accused of reproducing the effects of interest in a legally acceptable form. This challenge between form and substance is one of the most heated debates in contemporary Islamic finance.

From theory to practice: how does Islamic finance dispense with interest?

Murabaha, Ijara, Musharaka: the pillars of ethical financing

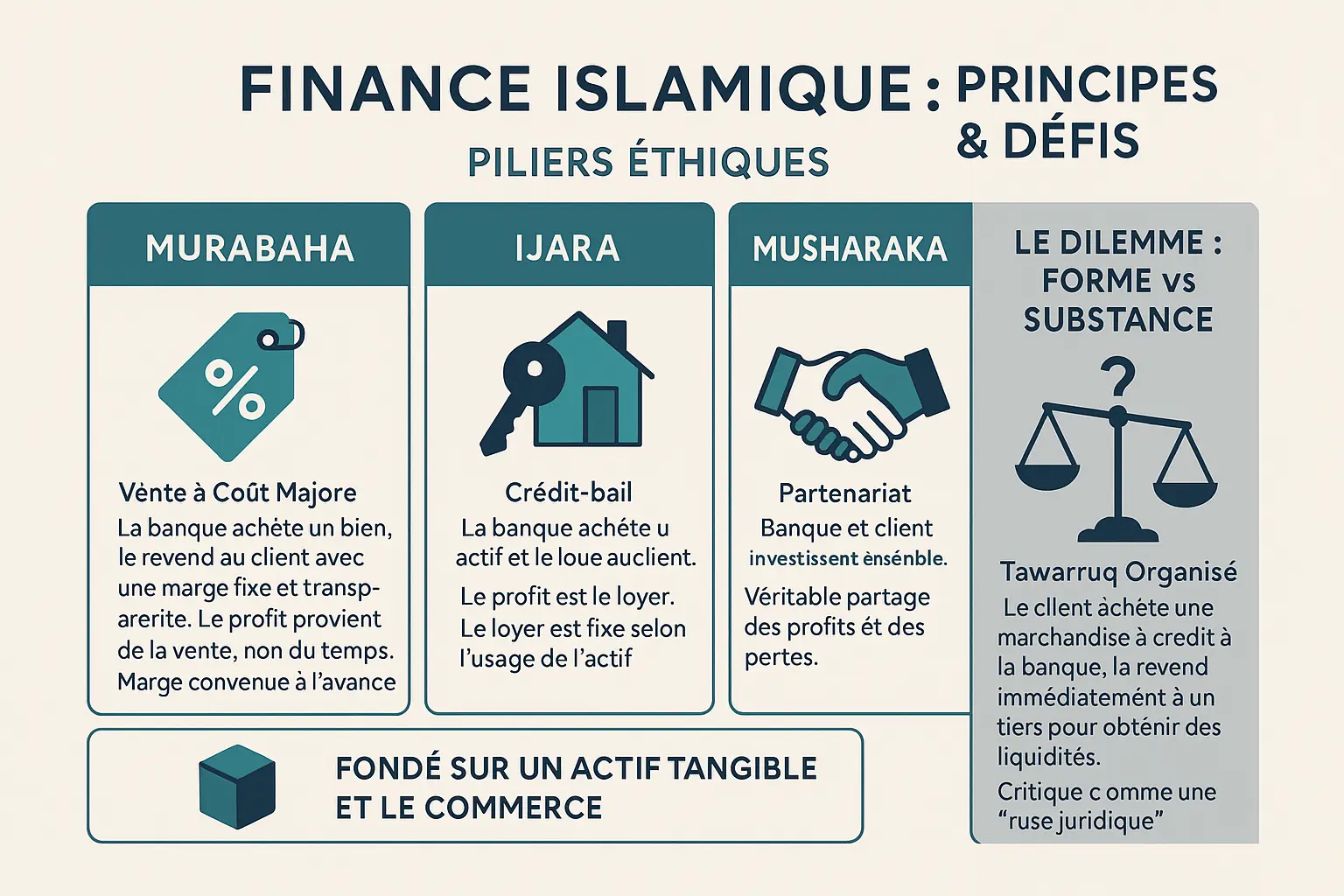

Islamic finance offers concrete solutions to replace interest-bearing loans. These models are based on tangible assets and real exchanges. Here are the three main pillars, enriched by operational details:

- Murabaha (cost-plus sale): The bank buys an asset (e.g. real estate) and then sells it back to the customer at a pre-determined margin. This margin takes into account factors such as acquisition costs, the risk associated with holding the property and the length of the deferred payment period. It varies between 5% and 35%, depending on the duration and price. Find out how this applies to halal real estate.

- Ijara (leasing): The bank buys an asset (vehicle, building) and rents it to the customer. The rent is calculated using an affordability simulator, taking into account the customer's income, expenses and an annual profit rate (e.g. 4% over 15 years). At the end of the contract, the customer can purchase the asset. Compare with Islamic banks.

- Musharaka (partnership): Bank and customer invest together in a project. Profits are shared according to a predefined ratio (e.g. 60/40), losses according to the proportion of contributions. In a decreasing Musharaka for real estate, the customer gradually acquires the bank's shares, reducing the rents paid. This is the model closest to the principles of profit and loss sharing.

These models eliminate the predictable exploitation of interest-based systems. Their strength lies in the transparency of the mechanisms and their anchoring in real transactions. For example, in Musharaka, an entrepreneur and a bank each invest €50,000 in a business: profits are shared 50%, and losses are shared equally, encouraging caution and dialogue.

The Islamic finance dilemma: form versus substance

Even if these alternatives respect the rules of Shari'ah, some practices attract criticism. Organized Tawarruq is at the heart of the debate. How does it work? The customer buys an asset on credit from the bank (e.g. precious metals), then immediately sells it to a third party to obtain cash.

This mechanism is perceived as a legal ruse (hilah). The intention is not to trade the property, but to obtain a disguised loan. This conflict between form and substance illustrates a major challenge: respecting the rules while meeting the needs of the market. Although legal according to the letter of the law, this model is criticized for reproducing the effects of interest without respecting its spirit. For example, a customer using Tawarruq for a €100,000 loan obtains the funds via a resale of metals, but the system remains an indirect and costly alternative.

The risk of hidden riba in practices such as Tawarruq raises ethical questions. The Majma' al-Fiqh al-Islami itself has expressed reservations, stressing the importance of not reducing Islamic finance to a mere dressing-up of conventional methods. These debates show that the industry needs to move towards more transparent models, such as Musharaka, to fully embody the values of justice and sharing.

Socio-economic implications: towards a fairer financial system?

A model for social justice and financial inclusion

En interdisant le Riba, la finance islamique lie le financement à l’économie réelle, évitant l’accumulation de richesse sans effort productif au bénéfice de la justice sociale. Selon la Banque Islamique de Développement, 9% des habitants de pays musulmans évitent les banques conventionnelles pour des raisons religieuses, représentant des millions de personnes éligibles à des services conformes. Dans le Maghreb, 27% des adultes justifient leur exclusion bancaire par des convictions religieuses, contre 3% dans les pays du Golfe.

Cette disparité s’explique par la présence d’institutions islamiques, car des outils comme le Qard-Hassan et la Murabaha répondent aux besoins de la microfinance. Un partenaire peut ainsi obtenir un financement via la Musharaka, un partenariat où la banque et l’entrepreneur partagent bénéfices et pertes.

However, the cost of compliance committees (up to $200,000 a year per expert) limits accessibility. In some rural areas, this additional cost makes Islamic microcredit less competitive. Despite this, Islamic finance has seen annual growth of 15-20%, managing over $2,000 billion in assets, proof of its potential.

Stability and efficiency: the promises of an uninteresting economy

Risk sharing reinforces economic stability by aligning income with asset performance. Unlike fixed rates, remuneration adjusts to real profits, limiting speculative bubbles. In 2008, Islamic banks proved more resilient thanks to their roots in the real economy. Resource allocation is based on project profitability rather than solvency, promoting sustainable growth. This ethical approach reconciles economic development and social responsibility, as underlined by studies on inclusive finance.

Riba and interest: between ethical compliance and industry challenges

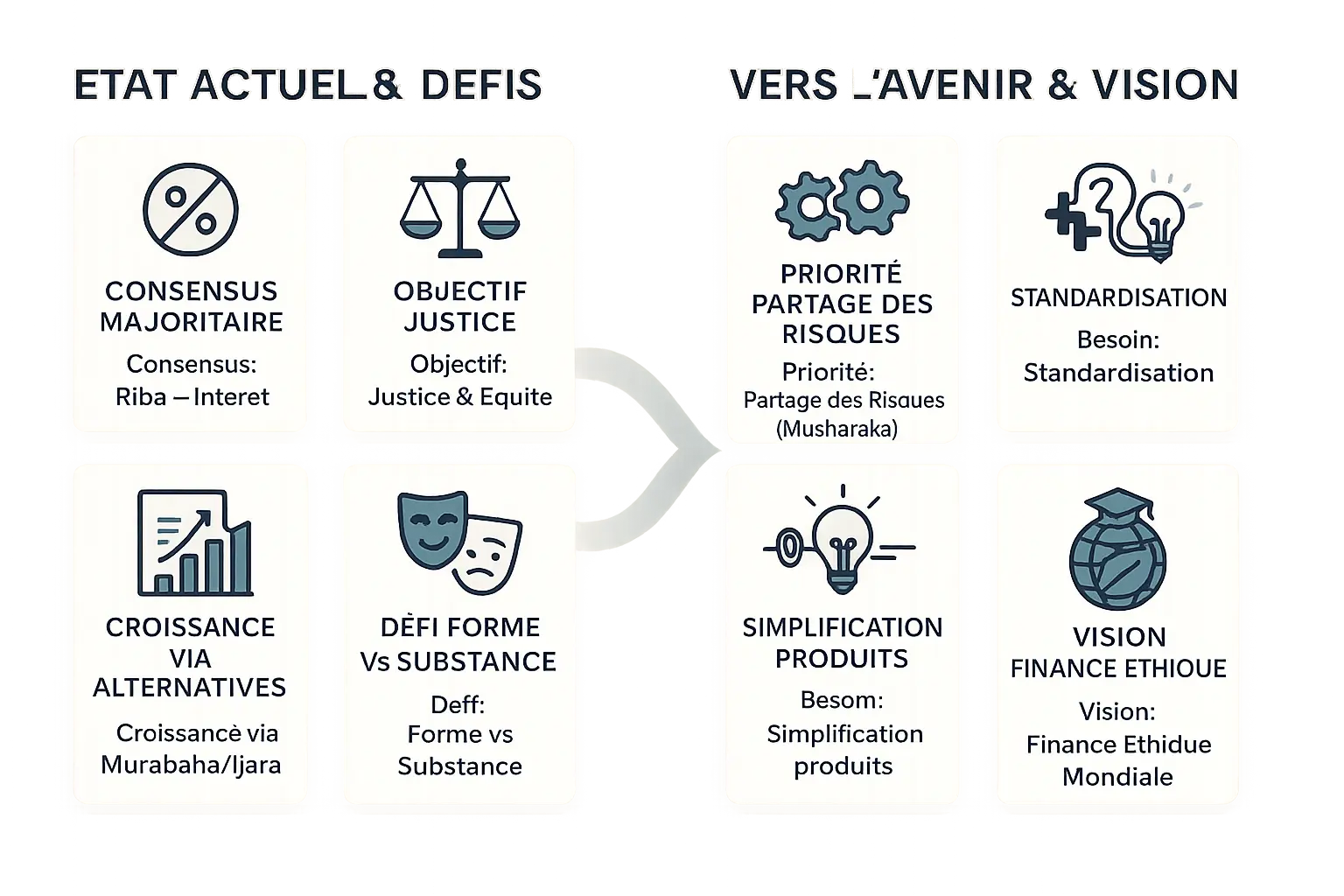

Summary: a clear consensus for a demanding ideal

The majority consensus between AAOIFI and Majma' al-Fiqh al-Islami is unambiguous: modern bank interest is equivalent to prohibited Riba. This prohibition, rooted in sacred texts, aims to promote justice and equity by eliminating exploitative mechanisms. Alternatives such as Murabaha (cost-plus sales) and Ijara (leasing) have enabled the industry to grow, reaching 3,178.21 billion USD in 2024. However, their complexity and proximity to conventional models have drawn criticism.

Risk-sharing, the heart of Musharaka (partnership), remains under-utilized in favor of debt structures. This paradox illustrates the challenge of combining commercial growth with fidelity to principles. The denunciation of the Tawarruq organized by the Majma' underlines the need to distinguish the legal form from the ethical spirit.

Challenges for authentic Islamic finance

To fully embody its values, Islamic finance must overcome a number of obstacles. Standardization of norms remains crucial: divergences between legal schools (Hanafi, Shafiite, etc.) fuel uncertainty. Product simplification is also essential to reach low-income populations, who are often put off by high costs.

By 2023, 70% of Islamic banking assets will be concentrated in the Middle East, revealing under-exploited potential in other regions. Consumer education, the key to trust, must adapt to the expectations of young people (50% digital adoption among millennials) and to ESG imperatives (Environment, Social, Governance). Finally, the transition to models such as Musharaka, integrating solidarity and sustainability, would position Islamic finance as a credible alternative to conventional finance, advocating ethical finance anchored in trust and the common good.

Riba, condemned by the majority consensus, embodies justice and fairness in the economy. Despite the dominant Murabaha, risk-sharing (Musharaka) remains essential. Standardization and simplification will strengthen the credibility of ethical finance, proving that it meets global challenges.

FAQ

Why is Riba forbidden in Islam?

Riba is forbidden in Islam not as a simple legal rule, but as an ethical pillar designed to protect social and economic justice. The Koran clearly condemns it, describing it as an unjust practice that exploits the most vulnerable and concentrates wealth. In Sura Al-Baqarah (2:275), it is said that those who practice Riba "stand like one whom the Devil has struck mad", underlining its devastating impact. The Sunnah reinforces this prohibition by distinguishing two forms: Riba al-nasi'ah (interest on time-bound loans) and Riba al-fadl (unequal exchanges of goods of the same kind). The ultimate aim is to promote transactions based on risk-sharing, where profit derives from real economic activity, and not simply from holding money.

What's the difference between Riba and modern bank interest?

AAOIFI and Majma' al-Fiqh al-Islami consider modern bank interest to be equivalent to Riba prohibited by the Koran. According to these institutions, any predetermined excess on a loan, whether simple, compound, low or high, falls under the category of Riba al-nasi'ah. This position is based on a consensus (Ijma') among contemporary scholars, who see interest as a "devouring" of other people's wealth without any productive counterpart. However, a minority of scholars, such as Mohammad Omar Farooq, dispute this equivalence, arguing that the prohibition would only cover excessive usury or subsistence lending, and not moderate interest in a commercial context. This debate reflects the tension between a literalist reading of the texts and an interpretation focused on the ethical objectives of the Shari'ah (maqasid), such as the fight against injustice.

What is the interest rate of an Islamic bank?

Unlike conventional banks, Islamic banks do not charge interest in the traditional sense. Their remuneration comes from alternatives based on tangible assets, such as Murabaha (cost-plus sales) or Ijara (leasing). For example, in a Murabaha contract, the bank buys an asset (real estate, car) and sells it back to the customer at a fixed profit margin, with no time-based calculation. This "rate" is transparent and fixed from the outset, avoiding time-related increases. In this way, the total cost is determined by a legitimate commercial margin, in line with the principles of Islamic finance, which favors fairness and contractual clarity.

What are Riba bank charges?

Riba bank charges" refers to any excess charged on a loan or debt, considered a form of Riba al-nasi'ah. This includes interest on home loans, consumer credit or bond investments. For AAOIFI, this type of fee is strictly forbidden, as it corresponds to Riba prohibited by sacred texts. On the other hand, management fees that are not linked to a surplus on capital (such as service or portfolio management costs) are permitted if they reflect real costs. Islamic finance encourages models where fees are derived from productive activities (such as a trading margin or rent) rather than from holding money.

How to save without riba?

Pour épargner sans Riba, plusieurs options respectent les principes de la finance islamique. Les comptes d’épargne Wadiah offrent une garantie de capital sans intérêt fixe, avec des bonus facultatifs non contractuels. Les fonds de Musharaka (partenariat) permettent de partager les profits d’investissements dans des actifs réels (immobilier, entreprises halal). Les Sukuk (obligations islamiques) adossées à des actifs physiques sont une alternative aux obligations classiques. Enfin, les fonds caritatifs de purification (zakat) peuvent être utilisés pour éliminer les revenus non conformes (moins de 5% selon l’AAOIFI). Ces solutions allient conformité religieuse et rendement responsable, en alignement avec les objectifs de justice sociale.

What are the two main types of Riba?

The two main forms of Riba are Riba al-nasi'ah and Riba al-fadl. Riba al-nasi'ah concerns the excess on a loan or debt linked to time, such as today's bank interest. It is considered the most pernicious form, condemned directly by the Koran. Riba al-fadl, on the other hand, involves an unequal exchange of goods of the same kind (gold, silver, grain) without simultaneity, prohibited to prevent misappropriation of Riba al-nasi'ah. These distinctions, derived from revealed sources and classical jurisprudence, are intended to provide a framework for transactions to avoid exploitation and guarantee fairness.

What does the Koran say about Riba?

The Koran condemns Riba with unparalleled severity, calling it an act of "war against Allah and His Messenger" (Sura Al-Baqarah 2:279). In the same Sura (2:275), it is stated that "those who eat Riba only stand as one whom the Devil has struck mad", underlining its devastating nature. Sura Al-Imran (3:130) exhorts "not to consume Riba duplicated and multiplied", warning against its exponential multiplication. These verses, coupled with the teachings of the Sunnah, establish a clear framework: Riba is a social injustice that enriches without productive effort, in contradiction with the maqasid (objectives) of the Shari'ah, such as wealth preservation and justice.

Why are Livret A savings accounts considered haram?

The Livret A savings account is often considered haram because it generates interest, a form of Riba al-nasi'ah prohibited by the Koran and Sunnah. Although this product is low-interest, the surplus earned on the initial capital, however modest, is perceived as profit without risk-taking or economic compensation. The AAOIFI states that "the payment or receipt of interest is Riba", without distinction of rate. However, solutions do exist for Muslim savers: Wadiah accounts or profit-sharing funds (Mudarabah) offer transparent remuneration in line with Islamic values. These alternatives transform saving into an ethical act, where the gain is linked to the real performance of the assets.

How to become a property owner without Riba?

Becoming a homeowner without Riba is possible thanks to mechanisms such as Murabaha or Ijara. With Murabaha, the Islamic bank buys the asset (property, car) and sells it to the customer at a fixed profit margin, with no time-related increase. With Ijara, the asset is leased and then gradually purchased. These models avoid interest by being based on real transactions (purchase-resale, rental). However, challenges remain: costs can be higher due to complex structures or customs taxes. To reduce these differences, tax adjustments (as in Great Britain) aim to avoid double taxation. Thus, Riba-free ownership combines religious conformity and accessibility, although progress is needed to improve simplicity and affordability.