<meta name="google-site-verification" content="0S72xkYcSqqt100ZuIzn_Zif1zL8vIvcXUmc5Tjo10o" />

Key points to remember: Islamic banks are based on a clearly different philosophy, prohibiting interest and sharing risk. Despite their attractive ethics, their practice remains close to the conventional model, with Murabaha accounting for 80-90% of business, underlining the challenge of reconciling religious ideals and economic realities without becoming a mere "halal-certified copy" of the system they aim to transform.

Are Islamic banks really different? All too often, they are accused of copying the classical model under a halal veneer. Discover how Islamic finance, focused on ethics, transparency and the real economy, is confronting the realities of the global system, with its emblematic products such as Murabaha - often criticized for its structure resembling conventional loans - and Ijara, while practices vary from region to region. An honest insight into an alternative that is struggling to free itself from the shackles of the past, but retains all its potential to reinvent finance, restoring confidence to those seeking a fair and sustainable economy.

Contents

Islamic banks: a promise of ethics and justice?

An alternative to the conventional financial system

You've probably wondered whether your money could be put to better use in a fairer world of finance. Islamic finance offers a concrete response to this quest for meaning. It is based on three essential pillars: the prohibition of riba (interest), gharar (excessive uncertainty) and maysir (speculation). Unlike conventional banks, it requires a real material counterparty for each transaction.

Why is this model so attractive? Because it proposes a sharing of risks between the parties, like the Musharaka contract where investor and entrepreneur share profits and losses. It's a system that reconnects finance and the real economy, in theory. But is it enough to really distinguish it from traditional banks?

The foundations of a trust-based model

Imaginez un édifice dont les fondations déterminent la solidité. La finance islamique s’édifie sur des normes éthiques strictes encadrées par la Shari’ah. L’AAOIFI joue ici un rôle clé en standardisant ces pratiques à l’échelle internationale.

In practice, two products dominate: Murabaha (sale with profit margin) and Ijara (lease with purchase option). Although innovative, these mechanisms are not without their critics. Some consider them too similar to conventional loans, creating a gap between theory and reality.

The challenges are many: regional divergences in the application of principles, risks of imitation of the conventional model, and integration into a global financial system dominated by vested interests. However, initiatives such as Namlora show that halal and responsible finance can emerge, combining technology and Islamic values.

The philosophy of Islamic finance: money at the service of the real economy

A paradigm shift: banning injustice

Islamic finance breaks with conventional models by anchoring its principles in justice, equity and solidarity. It sees money as a means, not an end, to eliminating structural inequalities. Unlike systems based on fixed interest, it rejects speculation and guaranteed profits.

"Islamic finance seeks to transform money from a mere commodity to a tool at the service of human development, economic stability and social justice."

By prohibiting Riba (interest), it avoids toxic debt. An Islamic loan (Qard), for example, generates no surplus, protecting borrowers against excessive indebtedness.

The 5 pillars that set it apart

- Prohibition of Riba: Money does not produce profit on its own. Banks prefer Murabaha (sale with margin), where the bank buys an asset to resell it, eliminating interest.

- Prohibition of Gharar: Contracts must be clear. Vague clauses in real estate projects, for example, are forbidden to avoid abuse.

- Maysir ban: Speculative products (such as options) are prohibited. Investments must be based on the real economy, with profits linked to project performance.

- Backed by a tangible asset: Every transaction is linked to a tangible asset. An Islamic bank, for example, must physically own an asset before selling it, eliminating excessive securitization.

- Profit and loss sharing (PPP): Partnerships (such as Musharaka) oblige banks to assume risks. In the event of failure, they incur losses, unlike conventional banks, which receive fixed interest.

These principles form a unique model, according to IMF economists. By linking finance and the real economy, they limit speculative bubbles. For example, Sukuk (Islamic bonds) are backed by physical infrastructure, reinforcing the stability of the system.

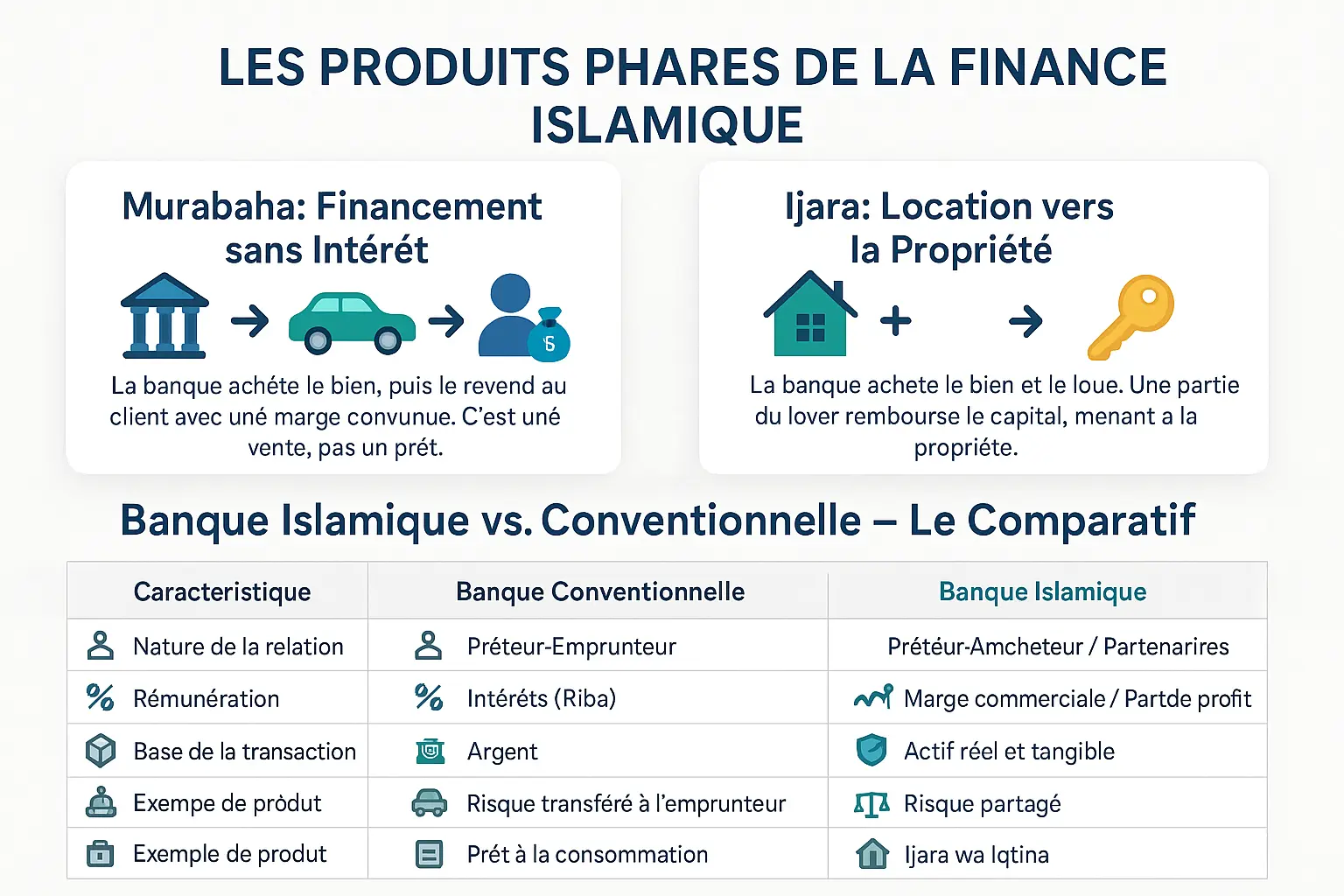

| Features | Conventional Banking | Islamic Bank |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of relationship | Lender-Borrower | Seller-Buyer or Partners |

| Compensation | Fixed or variable interest (Riba) | Sales margin or profit share |

| Transaction basis | Silver | Real, tangible assets |

| Risk management | Risk transferred to borrower | Risk shared between bank and customer |

| Product example | Consumer loans | Murabaha |

| Product example | Mortgage loan | Ijara wa Iqtina |

La Murabaha : financer un achat sans intérêt

La Murabaha incarne l’éthique de la finance islamique en évitant le riba. Exemple : un entrepreneur souhaite acheter un camion. La banque achète le véhicule, puis le revend avec une marge étalée en mensualités. Contrairement à un prêt, c’est une vente, échappant à l’interdiction des intérêts.

Un détail clé : la banque doit physiquement posséder le bien avant de le céder. Cela élimine le gharar (incertitude excessive) en liant la transaction à un actif réel. Ce mécanisme permet à des entrepreneurs sans apport de démarrer des projets, un principe central dans l’écosystème Namlora.

L’Ijara : la location qui mène à la propriété

L’Ijara incarne la stabilité des contrats islamiques. Imaginons un artisan souhaitant acquérir un atelier. La banque achète le local et le loue en versant une partie du loyer vers le capital. À la fin du contrat, la propriété est transférée. Contrairement au leasing conventionnel, la banque reste propriétaire de l’actif pendant la période, assumant les risques d’usure.

Ce modèle évite le maysir (spéculation) en alignant les intérêts des deux parties sur la réussite du projet. En Malaisie, des banques utilisent l’Ijara pour financer des énergies renouvelables, illustrant la flexibilité des produits islamiques pour soutenir l’économie verte, un axe clé de Namlora.

Banque islamique vs conventionnelle : le comparatif

Les différences structurelles résident dans la gestion du risque et la matérialité des actifs. Les banques classiques transfèrent tout le risque au client, tandis que les modèles islamiques comme la Mudaraba partagent profits et pertes. Par exemple, une startup en Indonésie a obtenu un financement sans apport, la banque devenant actionnaire temporaire via un partage des bénéfices.

Le tableau souligne que la finance islamique valorise des actifs tangibles. Un crédit immobilier classique génère des intérêts sur un simple prêt, alors que l’Ijara wa Iqtina lie chaque paiement à un bien concret. En Europe, des néobanques comme Gate2Bank utilisent la purification des revenus (tazkiyah) pour éliminer les bénéfices indirectement liés au riba, renforçant la confiance des investisseurs.

Les normes de l’AAOIFI jouent un rôle clé dans la standardisation. En recentrant les exigences sur la traçabilité des actifs pour les Sukuk, cet organisme réduit les dérives de certains pays asiatiques. Cette évolution marque une volonté de concilier innovation et conformité, un équilibre au cœur du projet Namlora.

The great divide: when practice deviates from the ideal

Copycat syndrome": a questionable resemblance

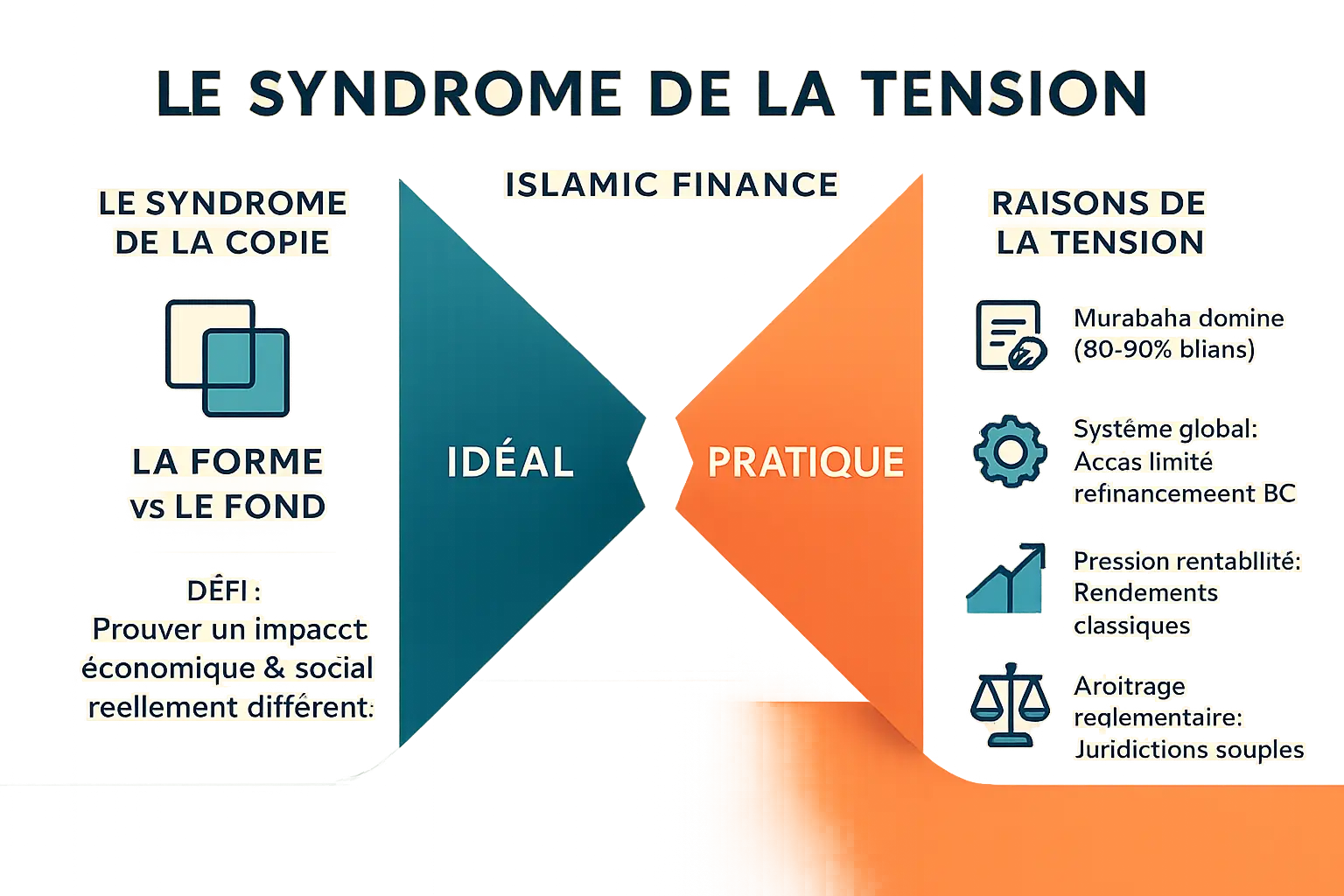

Islamic finance is based on clear principles: prohibition of riba (interest), gharar (excessive uncertainty) and maysir (speculation), with its roots in the real economy. Yet a paradox persists. The replication syndrome sums up this challenge: products that are legally compliant with Shari'ah law reproduce economic mechanisms similar to those of conventional banks. This situation calls into question their ability to embody an alternative model.

The biggest challenge facing Islamic finance today is not its legal compliance, but its ability to prove a distinct economic and social impact.

There are several reasons for this phenomenon. Firstly, the search for returns comparable to those on the traditional market is driving banks to favor simple, predictable contracts such as Murabaha. Murabaha, although based on a sale with margin, is used for 80-90% of Islamic balance sheets, imitating conventional loans. Secondly, integration into a global system dominated by interest forces banks to make adaptations that are sometimes contested. Finally, the pressure of profitability prompts compromises to remain competitive, distancing players from the ideal of profit and loss sharing.

The reasons for a model under stress

Islamic banks are struggling to differentiate themselves for four main reasons:

- Predominance of commercial contracts: According to academic studies, Murabaha dominates 80-90% of business, to the detriment of participatory contracts (Musharaka, Mudaraba). The latter, although more in line with the principles, are under-utilized due to their complexity and volatility. For example, a home loan via Musharaka, where the bank shares the risk with the customer, remains marginal compared to Ijara, a rental with purchase option more akin to classic leasing.

- Integration into a global system: Their exclusion from conventional refinancing mechanisms limits their flexibility. For example, Islamic banks do not have access to central bank facilities, forcing them to hold excess liquidity. During the 2008 crisis, some of them had to purify (Tazkiyah) income indirectly linked to riba, revealing their dependence on the conventional system.

- Profitability pressure: To attract customers, Islamic banks need to offer competitive returns. This constraint pushes them towards established structures, such as Murabaha, rather than innovative but risky models. For example, a customer wishing to finance an agricultural project via Musharaka might hesitate in the face of uncertain returns, preferring a fixed margin via Murabaha.

- Regulatory arbitrage: In a heterogeneous legal framework, some institutions favor flexible jurisdictions. Malaysia, despite its role as an innovator, is often criticized for Sukuk backed by intangible assets, bringing these products closer to conventional bonds. Conversely, the Gulf States, via the AAOIFI, impose stricter standards, limiting contested practices.

These challenges reveal a structural tension: how to remain true to one's principles while integrating into a global system. Namlora, as an ethical investment ecosystem, embodies one possible response. By highlighting halal companies and reinforcing transparency, it illustrates how a supportive network can put spirituality back at the heart of exchanges. Yet the road to harmonization remains long. Initiatives such as the standardization of AAOIFI norms or the development of Islamic money markets are essential, but they require a collective commitment to reconcile ethics and competitiveness.

One finance, many realities: the faces of Islamic banking around the world

Gulf, Malaysia, Europe: contrasting approaches

Islamic finance varies from region to region. In the Gulf, banks follow strict AAOIFI standards. Murabaha contracts require real ownership of assets, avoiding disguised borrowing. In Saudi Arabia, products such as Musharaka (partnership) embody risk-sharing. In the United Arab Emirates, Ijara dominates real estate financing.

In Malaysia, Islamic finance is an economic lever. Sukuk that can be traded on the secondary market are being developed, despite criticism of their proximity to conventional bonds. Nevertheless, the country remains **innovative, with environmentally-friendly products such as "green sukuk "**.

In Europe, Islamic banks are adapting to legal frameworks not designed for them. Income purification (tazkiyah) limits exposure to Riba. In France, Sharia-compliant products require AMF approval. In Switzerland, neo-banks such as Alawwal offer interest-free accounts, although their presence remains marginal.

The crucial role of ethics watchdogs

The Sharia Board validates product compliance. In Malaysia, the committees authorize fixed-income Sukuk. In the Gulf, interpretations remain rigorous: Saudi Arabia bans Malaysian Sukuk, deemed to be similar to conventional debt.

AAOIFI, based in Bahrain, harmonizes practices. Its standards are mandatory in countries such as Sudan. It sets strict rules, such as physical possession of the property in Murabaha, avoiding past abuses.

These committees issue fatwas and intervene in disputes. Their legitimacy is based on both religious and financial expertise. To guarantee their independence, AAOIFI recommends that they be appointed by a representative assembly, with no direct links to management.

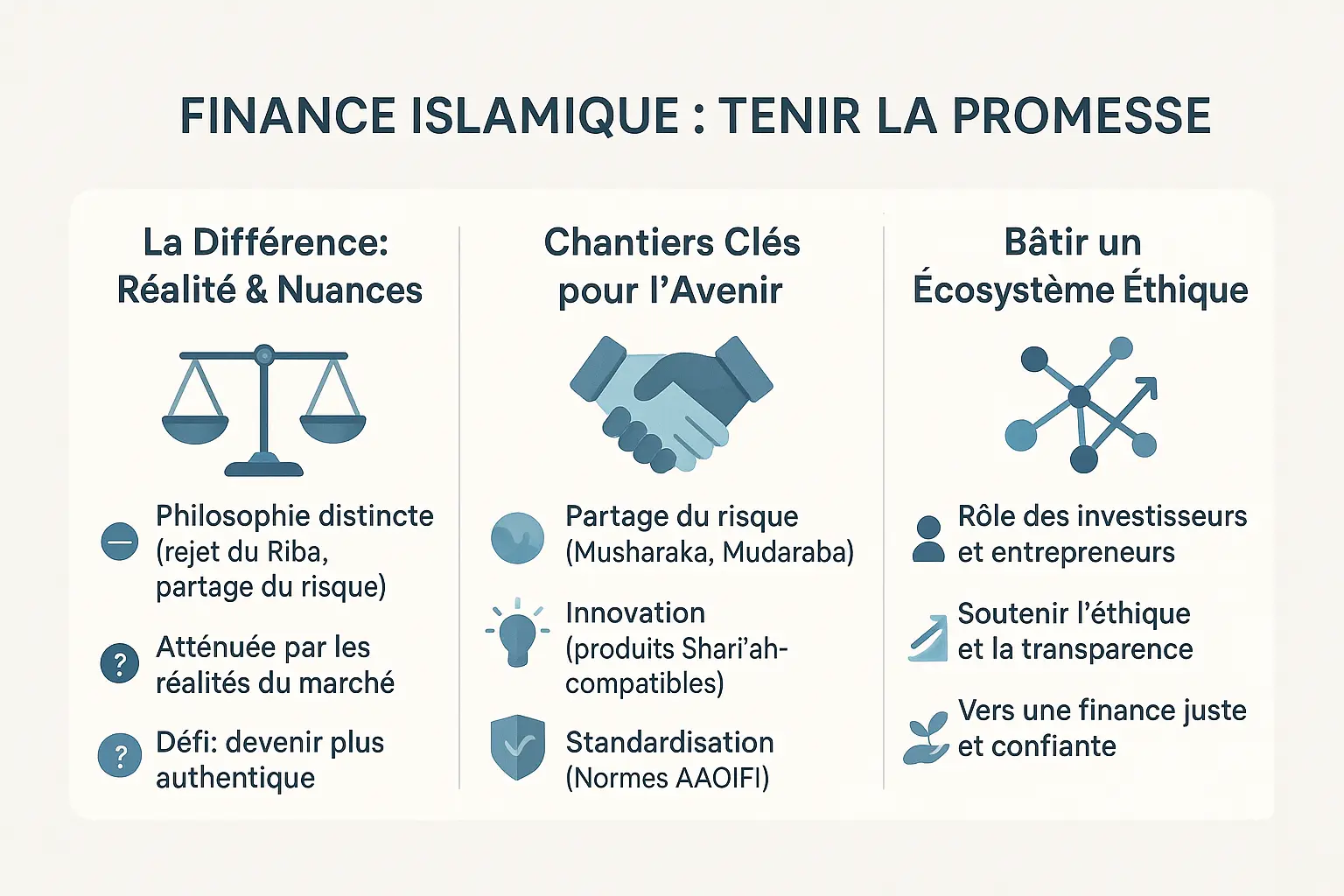

So are they really different? How Islamic finance can deliver on its promise

Yes, the difference is real, but there's still a long way to go.

Islamic banks are built on undeniably distinct ideological foundations: rejection of riba (interest), risk-sharing and links with the real economy. In practice, however, they face a number of practical challenges. The predominance of Murabaha contracts, sometimes considered too similar to conventional loans, illustrates the gap between ideal and application.

Despite this, this specificity remains a beacon of hope. The ban on gharar (excessive uncertainty) and maysir (speculation), combined with the obligation to anchor investments in a tangible asset, provides a solid foundation for more responsible finance. The challenge now lies in translating these principles into innovative practices that escape conventional reflexes.

Building sites for more authentic Islamic finance

For this vision to become a reality, several levers need to be activated:

- Refocus on risk sharing: Promote Mudaraba and Musharaka partnerships to boost the real economy, especially SMEs.

- Innovating beyond copying: Designing products adapted to today's realities without betraying Islamic ethics, such as halal fintechs.

- Reinforcing standardization: Giving greater weight to AAOIFI standards for international consistency, boosting confidence.

- Train industry players: Develop professional training courses that combine finance and Shari'a, such as those offered by Financia Business School.

Building an ethical investment ecosystem: everyone's role

Every player has a part to play in this evolution. Institutions must dare to think outside the box, regulators must provide the right framework, and investors must demand greater transparency. This collective movement will establish Islamic finance as a pillar of the sustainable economy.

Building an investment ecosystem that places trust and justice at the heart of exchanges is not an unattainable dream. Initiatives like Namlora prove that a concrete, ethical alternative can emerge. The future of Islamic finance is being built today, with the tools and the will of each and every one of us.

Islamic finance, rooted in a different philosophy, struggles to embody its values. For honoring our ethical commitmentIt must strengthen risk sharing, innovate without copying, and improve training and standardization. Together with citizens and players such as Namlora, it can build a finance aligned with convictions and the common good.

FAQ

How do Islamic banks differ from other banks?

Islamic banks are based on a radically different philosophy: they prohibit interest (riba), excessive speculation (maysir) and vague contracts (gharar). Their model requires a tangible link with the real economy (e.g., a car purchased via Murabaha must physically exist) and risk-sharing (e.g., a Musharaka partnership where both parties win or lose together). Unlike conventional banks, they avoid "making money out of money", preferring real sales or rentals. However, certain practices, such as repeated Murabaha, sometimes resemble loans at disguised interest, a fact that divides experts.

Do Islamic banks charge interest?

No interest rate in the traditional sense! The principle of riba (usury) is prohibited. Instead, Islamic banks apply profit margins to commercial transactions. For example, in Murabaha, the bank buys a good and then resells it at an agreed margin (e.g. 4.25% p.a.), but this is not interest: it's the price of a service. That said, some critics point to economic similarities with conventional loans, especially when contracts are renewed with no real link to the asset. This debate highlights the challenge of innovating without betraying Islamic ethics.

Are Islamic banks really Sharia-compliant?

Yes, but with nuances. Each Islamic bank is supervised by a Sharia Board, made up of religious scholars who validate the products. However, interpretations vary from one legal school or country to another. In Malaysia, certain practices tolerate mechanisms that are close to conventional, while the Gulf states require strict adherence. Furthermore, indirect exposure to riba (e.g. transfers via conventional banks) is managed by purification of income (tazkiyah), an almsgiving that eliminates impure gains. In short, conformity is an ideal under construction, not an immutable perfection.

How do Islamic banks generate interest-free income?

They earn money by selling services or sharing profits, not by charging interest. Murabaha, for example, is a resale with margin: the bank buys an asset (e.g. a computer) and then resells it on credit. Ijara (leasing) generates income through rental payments, with or without an option to purchase. In Musharaka or Mudaraba partnerships, the bank invests as a partner and shares profits/losses. Finally, management fees or commissions for services (e.g. transfers) round out the income. That said, the majority of income still comes from commercial contracts close to the loan, a paradox that the sector is trying to resolve.

Which is the best Islamic bank in France?

En France, deux acteurs se distinguent : Mizen, la première néobanque islamique 100% digitale, propose des comptes sans intérêt, une carte Mastercard halal et des frais transparents. UBAF (Union de Banques Arabes et Françaises), pionnière en Europe, spécialisée dans le Trade Finance islamique, collabore avec des banques du Golfe. Le choix dépend de vos besoins : Mizen s’adresse aux particuliers souhaitant un quotidien conforme, tandis qu’UBAF cible les entreprises. À noter : les deux doivent composer avec un cadre juridique français non optimisé pour la finance islamique, d’où des adaptations comme la purification des revenus issus du système classique.

What are the concrete advantages of an Islamic bank?

Les avantages résident dans trois piliers : 1. Éthique et transparence : Financer l’économie réelle (pas de spéculation), éviter les secteurs haram (alcool, jeux en ligne). 2. Partage des risques : En Musharaka ou Mudaraba, la banque investit avec vous et assume les pertes, un modèle plus juste que le prêt à intérêt fixe. 3. Impact social : Des critères ESG intégrés par essence (ex. : financement de PME halal) et une vision anti-concentration de la richesse. Cependant, ces avantages dépendent de la rigueur des pratiques : certaines institutions, sous pression de rentabilité, ressemblent à des banques classiques, surtout avec la Murabaha dominante (80-90% des contrats).

The interest rate in Islamic banks: how to understand it?

There is no "interest rate", but rather a profit margin in concrete transactions. For example, in Murabaha, the bank buys a car and then sells it on credit at a margin of 4.25% per annum, fixed from the outset. This is not interest: it's the price of a fractional payment facility. The essential difference? This mechanism is linked to a real asset. On the other hand, if this margin is used to compensate for late payment (e.g., penalties paid to a charity), it reinforces ethics. The "margin" is therefore a legal profit-making tool, but its application remains a subject of debate to avoid abuses.

What do you think of 570Easi, the Islamic neobank?

570Easi represents a turning point: a 100% halal mobile bank for Muslims in France. Its strengths? Interest-free accounts, a compliant Mastercard, and partnerships in halal real estate (via Ijara). On the other hand, its young age (launched in 2020) and the complexity of innovating in a non-optimized legal framework pose challenges. Opinions emphasize its educational value (ideal for beginners in Islamic finance), but also its limitations: few diversified savings products compared to traditional funds. In the long term, its success will depend on its ability to broaden its offering while remaining faithful to Sharia law, a delicate but hopeful balance.

Which Islamic site is the most reliable for understanding these issues?

For an overview, Namlora is the reference. This site combines financial expertise and fidelity to Islamic principles, with an educational approach and resources for investing in the real economy (e.g. halal projects, ethical SCPIs). Unlike generalist platforms, Namlora focuses on the link between Islamic finance and responsible development. Its dossiers on Murabaha, Ijara and Sukuk help to distinguish between virtuous practices and the risks of "halal-certified copies". In short, it's a bridge between Islamic ethics and financial reality, ideal for investors wishing to reconcile faith and returns.