<meta name="google-site-verification" content="0S72xkYcSqqt100ZuIzn_Zif1zL8vIvcXUmc5Tjo10o" />

Key points to remember: Although Islamic finance is based on the three anti-speculation pillars (riba, gharar, maysir), it is not immune. According to Dr. Lahlou, its resilience varies from product to product and country to country, with drifts such as asset-based Sukuk and Tawarruq. The challenge is to strengthen transparency and ethical intent in order to preserve its real roots, the key to responsible investment.

What is speculation in Islam? Many believe that Islamic finance is immune to it, thanks to its prohibitions on riba, gharar and maysir, but the reality is more complex. Dr. Mohammed Talal Lahlou's study shows that certain products, such as poorly structured Sukuk or Islamic derivatives, open up loopholes. Even in regulated systems, practices such as organized tawarruq or futures sales in Malaysia demonstrate that speculation can infiltrate. Find out how these deviations highlight the importance of increased vigilance on the part of players to align practice with the ethical ideal of halal investment.

Contents

Speculation, a concept often misunderstood in Islamic finance

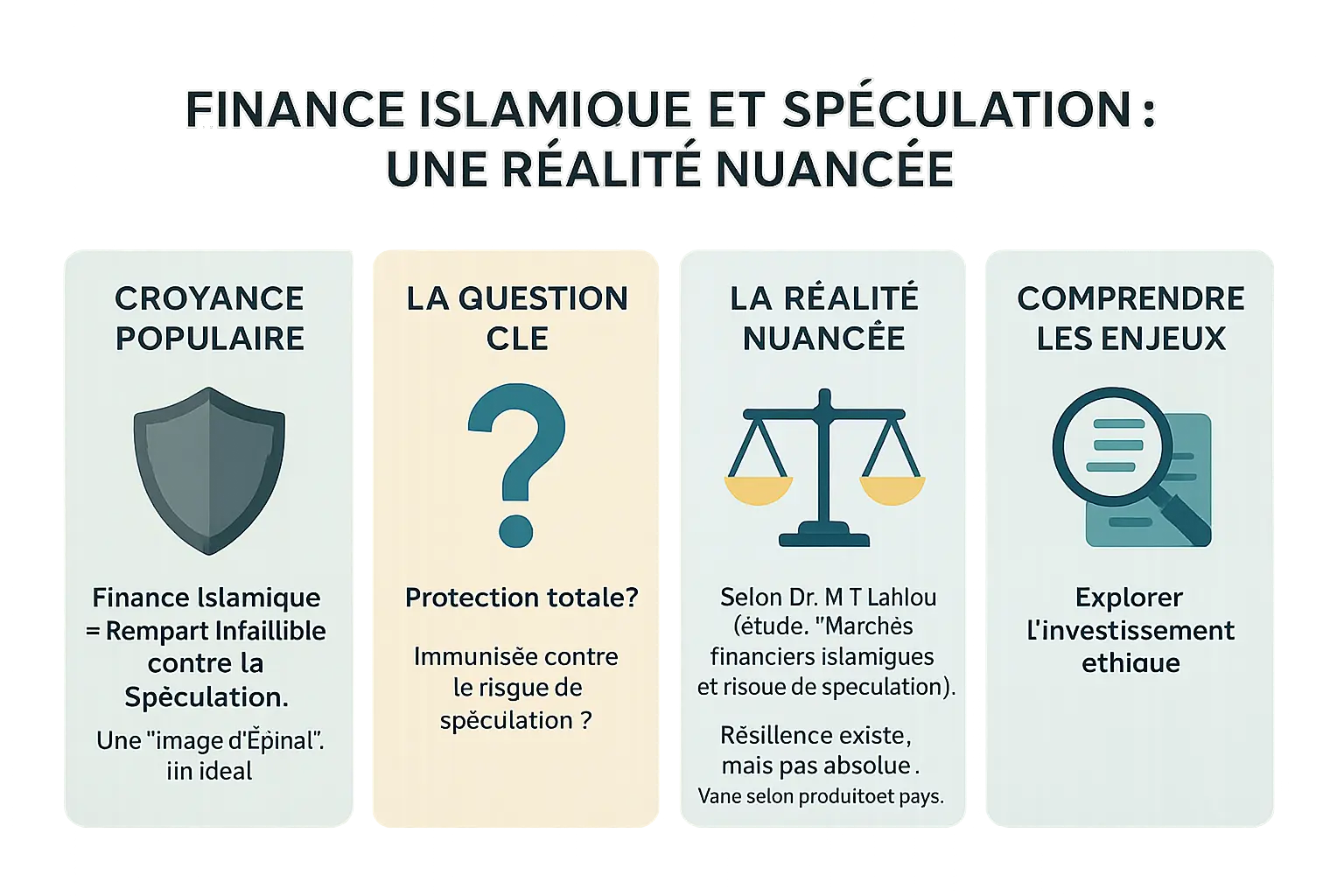

Beaucoup imaginent la finance islamique comme un bastion inébranlable contre la spéculation. Après tout, ses fondations interdisent le riba (intérêt), le gharar (incertitude excessive) et le maysir (jeu de hasard). Une idée séduisante, presque une image d’Épinal.

Pourtant, une question cruciale se pose : cette protection est-elle réelle ou simplement théorique ? La finance islamique est-elle vraiment immunisée contre le risque de spéculation, ou des fissures existent-elles dans ce système réputé éthique ?

Pour y répondre, tournons-nous vers les travaux du Dr. Mohammed Talal Lahlou. Dans sa thèse « Marchés financiers islamiques et risque de spéculation », il démontre que la réalité est plus nuancée. Si les principes sont robustes, leur application varie selon les pays et les produits.

Son analyse révèle un constat clair : les failles existent. Des sukuk adossés à de la dette aux murabaha utilisés comme prêts déguisés, les dérives sont possibles. La Malaisie autorise même des produits comme les futures, malgré l’interdiction théorique.

Cette section posera les bases d’un débat essentiel : comment préserver l’esprit éthique de la finance islamique face aux réalités des marchés ? Une réponse à découvrir dans les lignes suivantes.

Defining speculation: beyond buying and selling

What is speculative activity?

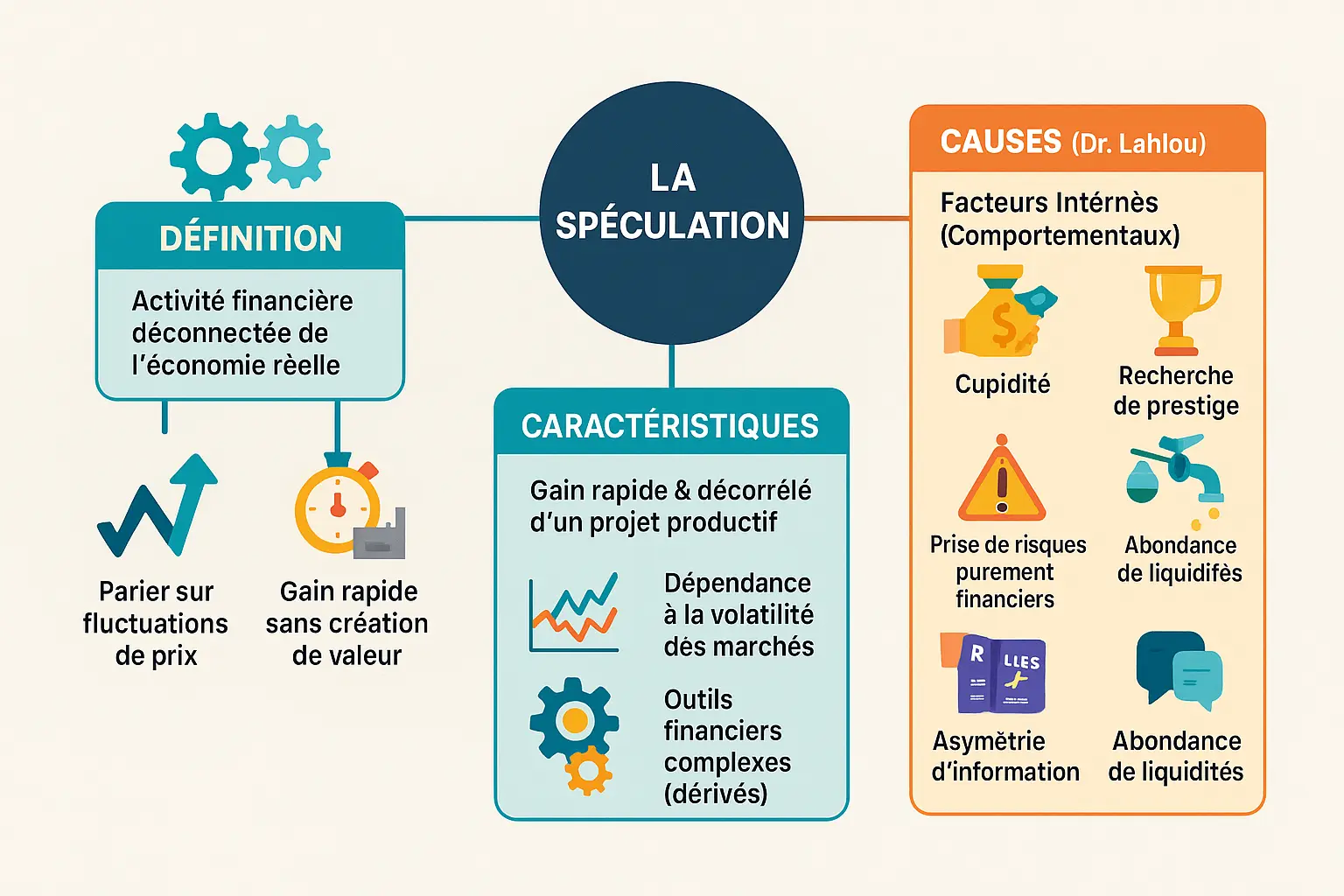

Speculation is more than just buying and selling. According to Dr. Mohammed Talal Lahlou, it is a financial activity disconnected from the real economy, where the aim is to profit from price fluctuations for a quick gain. Unlike investment, which is rooted in the creation of value through production or employment, speculation is based on financial bets.

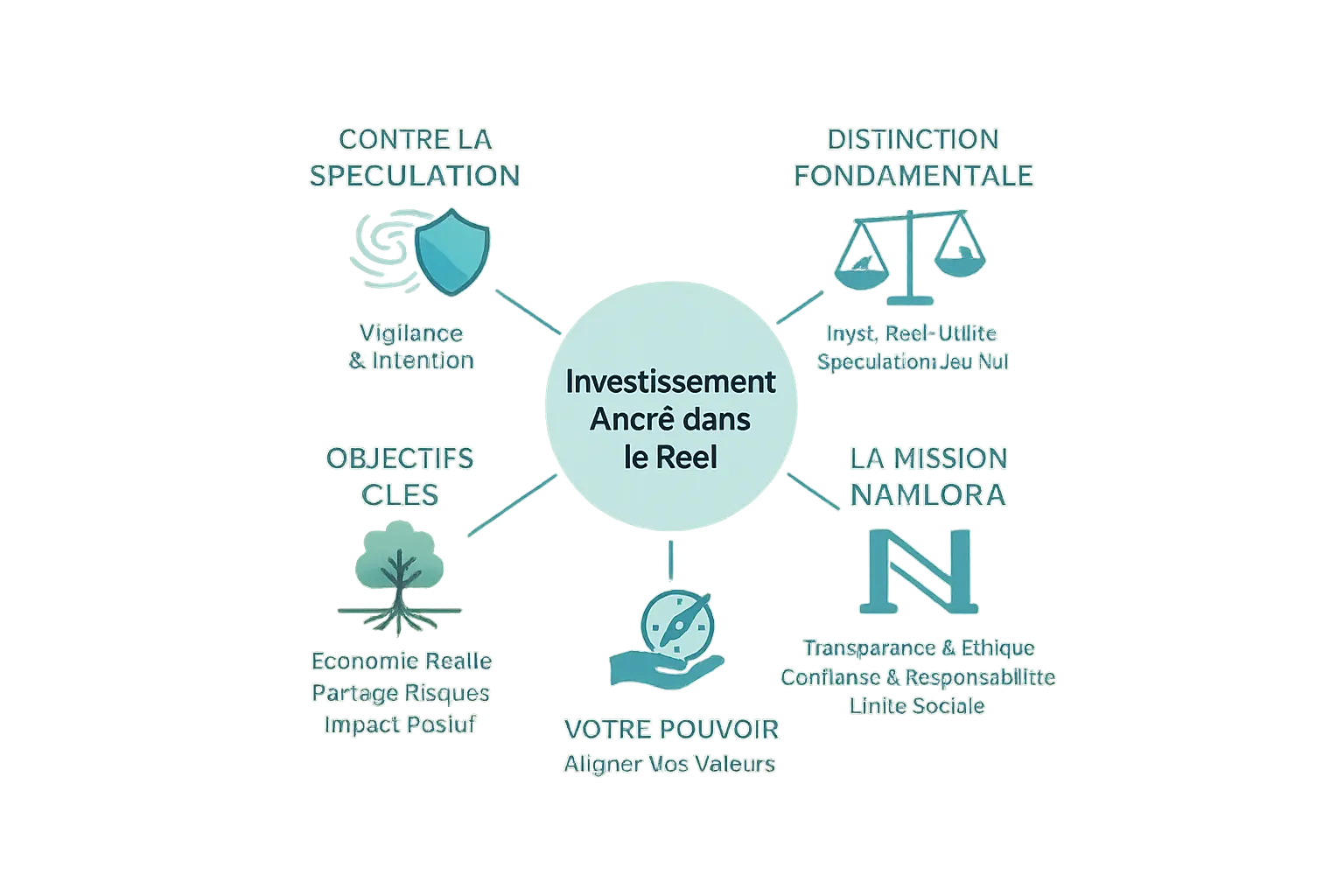

Namlora, in advocating a halal and transparent economy, reminds us that ethical investment must be based on tangibility and risk-sharing. Speculative activity, even when disguised as an Islamic product, betrays this spirit if it focuses solely on price variations.

The characteristics and causes of speculation

- Quick win, uncorrelated with a productive project.

- Dependence on market volatility and uncertainty.

- Use of tools such as derivatives and short sales.

- Taking purely financial risks, unrelated to the management of a tangible asset.

Two families of causes explain this dynamic: internal (behavioral) factors such as greed or addiction to complex products, and external (structural) factors such as deregulation or abundant liquidity. These causes interact to create an environment conducive to speculation.

For example, products such as Sukuk, theoretically backed by real assets, are sometimes structured like conventional bonds. This reintroduces speculative risks, as Dr. Lahlou points out in his analysis of the flaws in the system.

Speculation is as much a result of behavior as of economic structures. It challenges ecosystems like Namlora, committed to putting justice and spirituality back at the heart of trade.

Islam's theoretical bulwarks against speculation

The 3 fundamental prohibitions

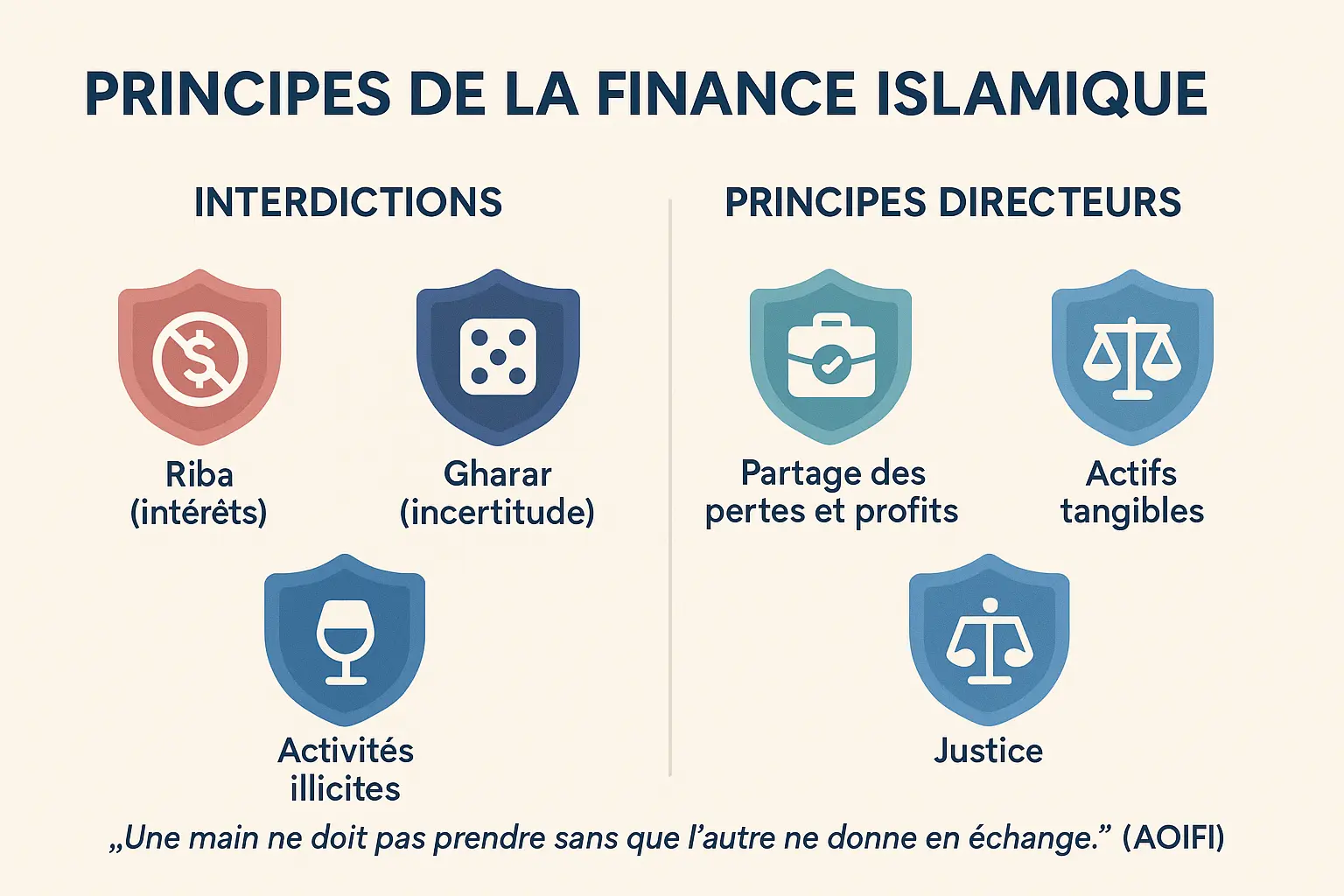

Islamic finance is based on three pillars designed to limit speculation: Riba, Gharar and Maysir. These principles provide a framework for ethical economic practices.

Riba, or usurious interest, is forbidden because it creates an imbalance between lender and borrower. Money must not generate profit without effort or risk, ensuring that wealth comes from productive assets.

Gharar prohibits excessive uncertainty in contracts. For example, selling an unowned asset is considered Gharar. This rule eliminates products that are disconnected from the real economy, such as speculative derivatives deemed too uncertain.

Maysir prohibits gambling or zero-sum transactions, where one player's gain results from another's loss. This excludes betting, lotteries or speculative trading, aligning finance with social values.

The 2 positive guiding principles

The aim is not to bet on the markets, but to finance real growth by sharing the risks and rewards of work, for a fair economy.

Islamic finance requires every transaction to be linked to a tangible asset, supporting the real economy, not abstract bets. Profit and loss sharing binds parties to the results of an investment, avoiding one-sided gains.

AAOIFI provides a framework for these rules, prohibiting non-compliant derivatives such as swaps and options. It requires total transparency to avoid abuses, such as automatic rollovers in Murabaha.

Halal investment vs. haram speculation: how to tell the difference?

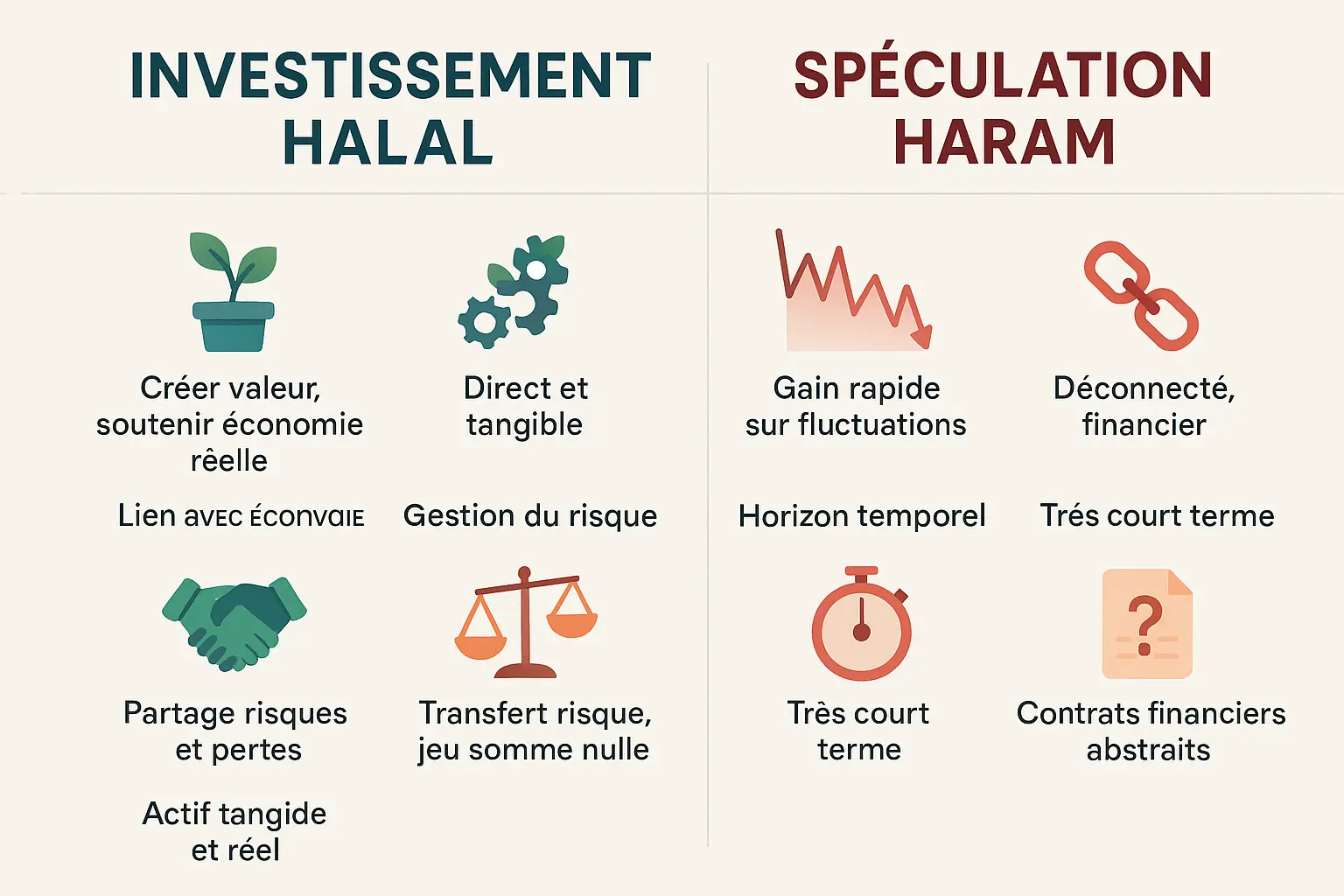

To help you distinguish between Sharia-compliant investment and prohibited speculation, here's a comparative table of key criteria.

| Criteria | Halal-compliant investment | Forbidden speculation (Haram) |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Creating value, supporting a real economic project | Make a quick profit on price fluctuations |

| Link to the economy | Direct and tangible (production, services, real estate...) | Disconnected, purely financial |

| Risk management | Sharing risks and losses between parties | Risk transfer, zero-sum game |

| Time horizon | Medium to long term | Very short term |

| Type of asset | Real, tangible assets (real estate, company shares) | Often abstract financial contracts (derivatives) |

A concrete example of halal investment would be the acquisition of a property to rent out. Here, the investor supports the real economy by providing a housing service and shares the rental risk.

Another example: investing in a productive business such as a manufacturer of halal cosmetics. The investor participates in job creation and ethical innovation, benefiting from the results of the business.

Certification by a recognized body is essential to guarantee ethical investment. It assures investors that their funds are supporting compliant activities, avoiding speculative excesses.

In the Namlora ecosystem, these principles take on their full meaning. By bringing together investors and entrepreneurs, the aim is to put spirituality back at the heart of economic exchanges.

To find out more about tangible assets, discover how investing in tangible assets such as gold can enhance the stability of an Islamic portfolio.

Ihtikar: when Islamic tradition condemned speculation

In Islam, the fight against predatory economic practices is rooted in jurisprudence. Ihtikar, or hoarding of essential goods, embodies this vigilance. It involves the intentional stockpiling of vital commodities to create an artificial shortage and speculate on prices.

Hadiths condemn this practice. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ said, "Whoever practiceshoarding is certainly at fault " (Sahih Muslim). Economy should serve the community, not exploit it. A trader hoarding wheat in a time of crisis is acting against the collective interest, as are modern speculators manipulating the markets.

According to Dr. Lahlou, market manipulation persists today via derivatives or poorly conceived Sukuk. The logic remains the same: to substitute greed for economic justice. In the face of these abuses, Islamic ethics reminds us that fair finance must be based on transparency, tangibility and respect for the general interest.

In the digital age, tools may evolve, but Islamic principles still guide us. Fighting Ihtikar means refusing to reduce the economy to a game of quick profits. It means defending finance that is aligned with justice, stability and the creation of real value.

When practice departs from theory: the grey areas of Islamic financial markets

Islamic finance, although based on clear principles, reveals gaps between theory and practice. As Dr. Lahlou points out,

Islamic finance is resilient in the face of speculation, but this resilience is nuanced and depends on the rigor of the players involved.

Some structures, although apparently compliant, border on the limits of Sharia prohibitions.

Sukuk: asset-backed or asset-based?

Les Sukuk, censés représenter une part réelle d’actifs, relèvent souvent de la catégorie « asset-based » (basés sur des actifs) plutôt que « asset-backed » (adossés). Les investisseurs détiennent des droits sur les bénéfices sans propriété légale des actifs. En cas de défaut, ils sont traités comme des créanciers, les rapprochant des obligations classiques. L’AAOIFI a déjà souligné en 2008 que beaucoup manquaient de substance sharia, ressemblant à de la dette conventionnelle.

Murabaha: a loan in disguise?

Murabaha, or sales with a profit margin, is hijacked by "rollover" (automatic renewal), transforming this structure into a disguised interest-bearing loan. AAOIFI standard 59 prohibits this practice, pushing banks towards more complex models that are sometimes unsuitable for smaller players.

Tawarruq: forbidden but used technique

Organized Tawarruq, where a financier facilitates the immediate resale of a property, is deemed illegal by the International Islamic Fiqh Academy.. This ruse circumvents the prohibition of riba and feeds debt without creating value.

Islamic derivatives: the Malaysian exception

Derivatives are rejected for their gharar, but Malaysia allows palm oil futures (FCPO), despite academic criticism of their speculative nature. This approval highlights the tensions between compliance and competitiveness.

Finally, Sharia compliance also depends on intention and impact. As Dr. Lahlou reminds us, these elements define the legitimacy of a product, not just its legal form. Islamic finance must therefore remain vigilant to preserve its ethical essence.

How can Islamic finance be strengthened in the face of speculative risk?

If Islamic finance is to preserve its essence, it must evolve without reproducing the excesses of conventional finance. Dr. Mohammed Talal Lahlou's teachings show that resilience depends on constant vigilance and strategic choices.

Here are the essential levers for anchoring Islamic finance in its ethical and productive role:

- Prioritize economic and ethical purpose over mere formal compliance. The spirit of Islamic principles must guide every product, above and beyond accounting standards.

- Increase transparency in operations, fees and profit/loss sharing mechanisms. Independent audits and clear disclosures are essential.

- Creating innovative solutions rather than mechanically adapting conventional tools. The examples of social Sukuk and halal robo-advisors illustrate this approach.

- Define a minimum holding period for assets to discourage very short-term transactions, favoring sustainable investment.

- Harmonize regulatory frameworks between countries to avoid tax or legal arbitrage, as observed in Malaysia.

Islamic finance must not become a disguised reflection of conventional finance. Its role is to reconnect markets with the values of justice, solidarity and the creation of real value. Technologies such as blockchain and artificial intelligence can contribute to this, provided they respect the spirit of Sharia law.

Namlora embodies this vision by building a halal investment ecosystem that is ethical and connected to contemporary issues. The challenge is clear: to transform Islamic finance into a genuine alternative, not just a label.

⚠️ Disclaimer: Namlora is not an investment advisor. This article is educational and community-based. You alone are responsible for your financial decisions.

Our vision: ethical investment rooted in reality

Islamic finance sees itself as a bulwark against the excesses of speculation, thanks to its clear prohibitions on riba, excessive gharar and maysir. However, as Dr. Mohammed Talal Lahlou has shown, this protection remains partial in practice. Financial products, even halal ones, can sometimes slip into mechanisms akin to those of conventional finance.

Namlora' s approach is the opposite: it's not just about avoiding the forbidden, but supporting the real economy and generating a lasting impact. For us, investing means participating in the creation of value, sharing risks, and reinforcing trust between economic players.

The Namlora ecosystem, for example, offers opportunities in participative real estate, physical gold or community projects, always avoiding speculative excesses. Every investment decision is guided byIslamic ethics, transparency and social utility.

En choisissant un modèle qui valorise la stabilité, la responsabilité et la justice, chaque investisseur peut contribuer à un système financier plus juste. Parce que l’argent, dans l’Islam, n’est pas un but en soi, mais un outil au service de l’homme et de sa foi.

La finance islamique, dotée de garde-fous solides contre la spéculation, n’est pas immunisée. Ancrée dans l’éthique et l’économie réelle, elle exige intention vertueuse, transparence et partage des risques. En alliant rentabilité et impact social, elle propose une alternative alignée sur les valeurs, où chaque investisseur peut agir en conscience.

FAQ

Qu’est-ce que la spéculation haram en finance islamique ?

La spéculation haram correspond à des pratiques financières déconnectées de l’économie réelle, fondées sur l’incertitude excessive (gharar), le jeu de hasard (maysir) ou l’intérêt (riba). Selon le Dr. Lahlou, c’est une activité visant à générer des gains rapides via la volatilité des marchés, sans création de valeur tangible. Par exemple, les ventes à découvert (short selling) ou certains produits dérivés islamiques, bien que parfois autorisés, sont régulièrement critiqués pour leur nature spéculative. L’interdiction vise à protéger les investisseurs et l’économie globale d’un système prédateur.

Qu’est-ce que la spéculation en Islam ?

En Islam, la spéculation désigne toute transaction financière ressemblant à un pari, où le gain dépend des fluctuations de prix sans lien avec un actif réel ou un projet productif. Le Dr. Lahlou la décrit comme une activité « anti-économique » : elle privilégie la cupidité au détriment de la solidarité. Contrairement à l’investissement, qui partage les risques et soutient l’économie réelle (comme un partenariat moudayana), la spéculation s’appuie sur l’asymétrie d’information ou des mécanismes complexes (ex: tawarruq organisé), éloignant les marchés de leur rôle éthique.

What is the most serious sin in Islam?

En finance islamique, le péché le plus grave reste l’usure (riba), souvent comparée à un « péché contre Dieu » dans le Coran (2:275). Elle symbolise l’enrichissement sans effort ni partage des risques, contraire à l’esprit de justice et de coopération. D’autres actes graves, comme la tromperie (gharar) ou les jeux spéculatifs (maysir), s’inscrivent dans cette logique, mais le riba est systémiquement dénoncé pour ses effets dévastateurs sur l’équité économique.

Quel trading est considéré comme halal ?

Le trading halal repose sur trois piliers :

Un lien avec l’économie réelle : Les actifs échangés doivent être tangibles (ex: actions d’entreprises productives, matières premières).

Transparence et partage des risques : Les contrats doivent éviter l’incertitude excessive (gharar) et garantir un partage des profits/pertes (ex: mourabaha respectant les normes AAOIFI).

Éthique et utilité sociale : Les secteurs à impact négatif (alcool, armes) sont exclus. En Malaisie, des produits comme les sukuk asset-backed illustrent une approche conforme, mais les dérivés trop proches des mécanismes classiques restent controversés.

Quelle est la chose la plus haram en Islam ?

D’un point de vue financier, l’usure (riba) est souvent qualifiée de « chose la plus haram », avec des versets clairs (Coran 2:278-279). Sur le plan social, l’accaparement (ihtikar) des biens essentiels (nourriture, médicaments) pour spéculer sur les prix est également fortement condamné par les hadiths. Ces pratiques, synonymes d’exploitation et d’injustice, illustrent une logique de profit pur, contraire à l’éthique islamique.

Est-il possible pour les musulmans d’investir en bourse ?

Oui, à deux conditions :

Des actifs conformes : Les sociétés investies ne doivent pas générer de revenus illicites (alcool, jeux) et respecter des ratios précis (ex: moins de 5% de revenus liés à l’intérêt).

Une approche à long terme : L’investissement halal favorise l’horizon temporel et le partage des risques, contrairement au trading à court terme spéculatif. Des initiatives comme les fonds mourabaha ou les takaful éthiques montrent que la bourse peut être alignée avec les principes islamiques, à condition de renforcer la transparence.

Pourquoi l’islam interdit-il l’usure d’argent ?

L’interdiction du riba découle de sa nature injuste : elle permet à celui qui prête de garantir un gain sans effort, tandis que l’emprunteur assume tous les risques. Le Dr. Lahlou souligne que cette dynamique crée des cycles de dette et d’inégalité, éloignant l’économie de son rôle social. En islam, l’argent ne doit pas « générer de l’argent » mécaniquement, mais circuler pour financer des projets productifs (ex: agriculture, commerce) dans un esprit de solidarité.

Pourquoi faire un crédit est-il haram en islam ?

Le crédit reste autorisé dans des cas nécessaires (ex: logement), mais l’intérêt qui l’accompagne est interdit. En islam, le prêt (qard hasan) doit être une aide désintéressée. Lorsqu’il s’agit d’un contrat commercial, le partage des risques est obligatoire (ex: mudaraba). Le crédit à intérêt fixe, en revanche, fige les gains du prêteur et accable l’emprunteur, ce qui contredit l’équité. Des dérives comme le tawarruq organisé, souvent critiqué comme un prétexte pour contourner cette règle, montrent l’importance de la vigilance.